|

When a patient complains of flashes and floaters, doctors may be wary of what they might find. These ambiguous symptoms may underscore a potentially serious issue.

This column reviews such presentations, what optometrists should look for and what to expect.

|

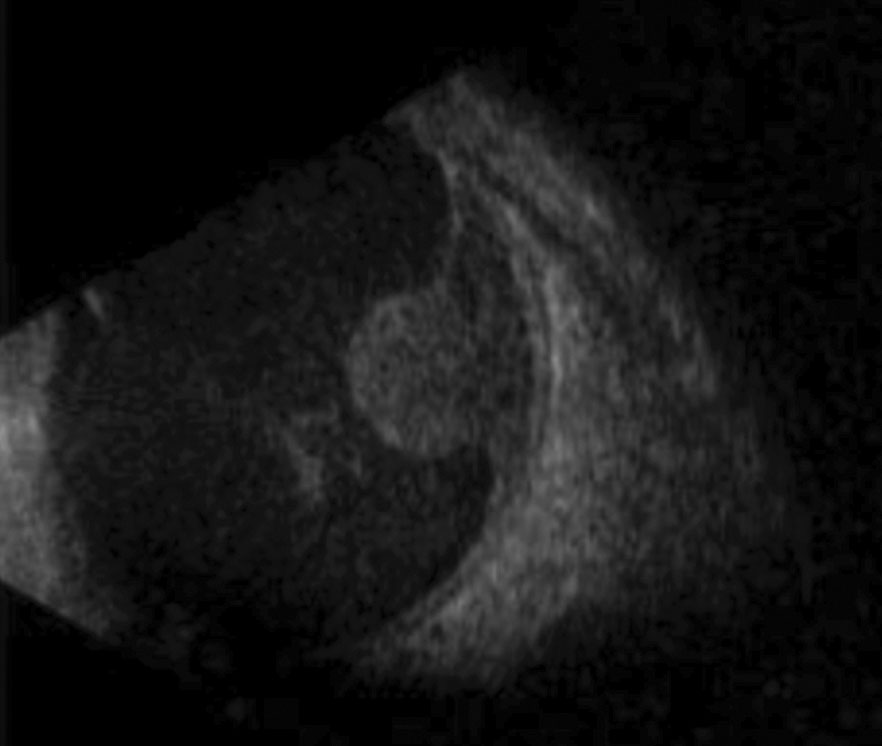

| This B-scan shows a large mass protruding forward through the retina, causing subsequent sensory detachment. Photo: Aaron S. Gold, OD. |

The Usual Suspects

As soon as a patient presents with flashes, most ODs will already have four potential diagnoses in mind.

- Ocular migraine with a preceding visual aura. This condition can frequently be teased out and confirmed with a thorough case history. For these patients, flashes occur in the form of scintillating lights from the periphery towards the central vision, leading to temporary field loss and subsequent nauseating headaches lasting one to several hours. In most cases, optometrists should dilate to confirm the diagnosis.

- Intraocular lens (IOL) related dysphotopsia. This one is tricky because it is often a diagnosis of exclusion. If scleral depression shows the retina is intact, dysphotopsia related to a new IOL may be to blame. Dysphotopsia is the leading cause of dissatisfaction following uncomplicated cataract surgery and is either positive or negative.1 Positive dysphotopsia manifests as a light in the form of a streak, starburst, flicker, fog or haze. Negative dysphotopsia is seen as a black line or crescent in a patient’s far peripheral vision.1 Researchers believe these visual phenomena are due to the square-edged IOL designs that became popular in the 1990s, or possibly a material with a high index-of-fraction coupled with a lens that has a low radius-of-curvature.1 Regardless, these patients should be sent back to their cataract surgeon.

- Posterior vitreous detachment (PVD). This usually develops after the vitreous gel separates from the internal limiting membrane of the retina. In most cases, the posterior hyaloid separation occurs without complication, resulting in a vitreous “floater” that casts a shadow of varying darkness on the retina. Occasionally, however, tractional forces can lead to a full-thickness tear, which could lead to rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. PVD is, in large part, an age-related event that occurs between the ages of 45 and 65.2 However, the vitreous may detach earlier in the highly myopic (>6.00D). Patients in their 50s have an expected prevalence of 25% while almost 90% of patients in their 80s will have already had a PVD.

- Retinal break or detachment. A 2009 review found that, when patients reported with an acute onset of flashes, floaters or both, a retinal break or tear was present 14% of the time.3

|

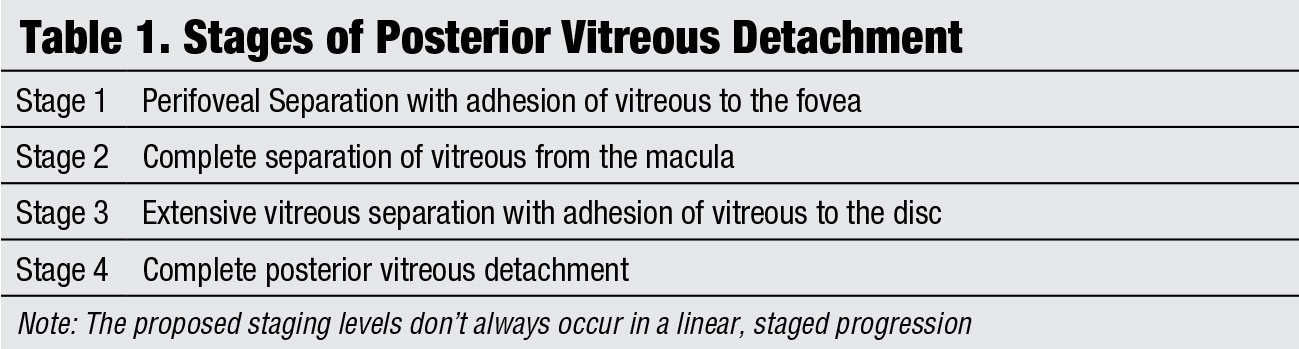

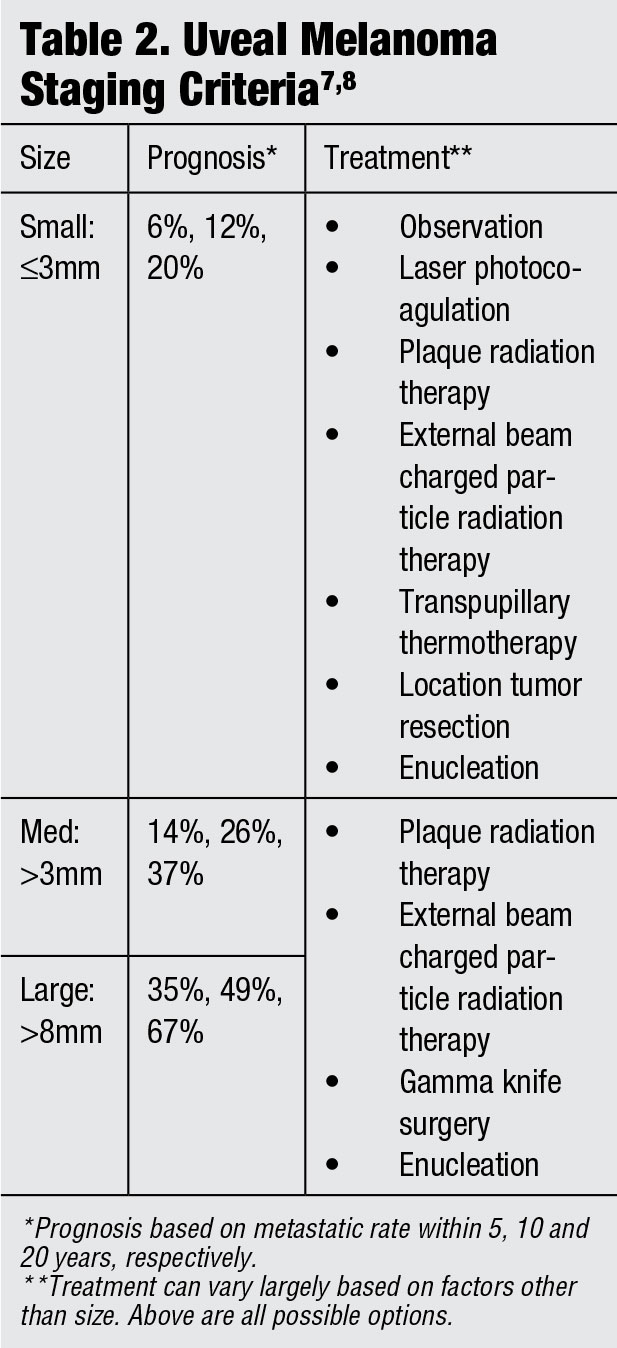

| Click chart to enlarge. |

In the same review, investigators determined two other predictive factors for retinal tear based on direct clinical examination:

- Vitreous hemorrhage (62% chance of a tear or detachment).

- Pigment dusting of the vitreous (88% probability).

Two-thirds of patients presenting with a vitreous hemorrhage had at least one break. A spontaneous vitreous hemorrhage can be a presenting sign or may occur subsequently.

Therefore, in all patients presenting with symptoms of flashes and floaters, a complete dilated examination using binocular indirect ophthalmoscopy with scleral depression, and at times, 3-mirror gonioscopy, is necessary in ruling out a complicated PVD with a retinal break, tear or detachment.

With that said, as the following case will illustrate, we cannot forget the “unusual suspects” when confronted with these symptoms.

|

Examination

A 61-year-old African-American male presented for an urgent care visit. He complained of sudden flashes and floaters upon waking, followed by vision loss in his right eye. He had an established decrease in vision in his left eye since childhood secondary to optic atrophy. He also added that he was recently hospitalized for a “lung infection.” He was treated with intravenous antibiotics while admitted and released a few days prior with a course of oral antibiotics.

The patient had an entering uncorrected visual acuity of light perception OD and 2/200 OS with no improvement on pinhole. Extraocular muscle testing was challenging due to an inability to fixate secondary to poor acuity, but was unremarkable with Doll’s head maneuver. Pupil testing demonstrated a 3+ APD OD. He was unable to see fingers during confrontation field testing OD and was constricted superior-nasal, inferior-nasal and superior-temporal OS. His anterior chamber angles were ¼:1 with Van Herick on slit lamp exam and demonstrated a closed angle morphology with gonioscopy. B-scan imaging was performed to evaluate retinal integrity since the patient was unable to be dilated at this time.

|

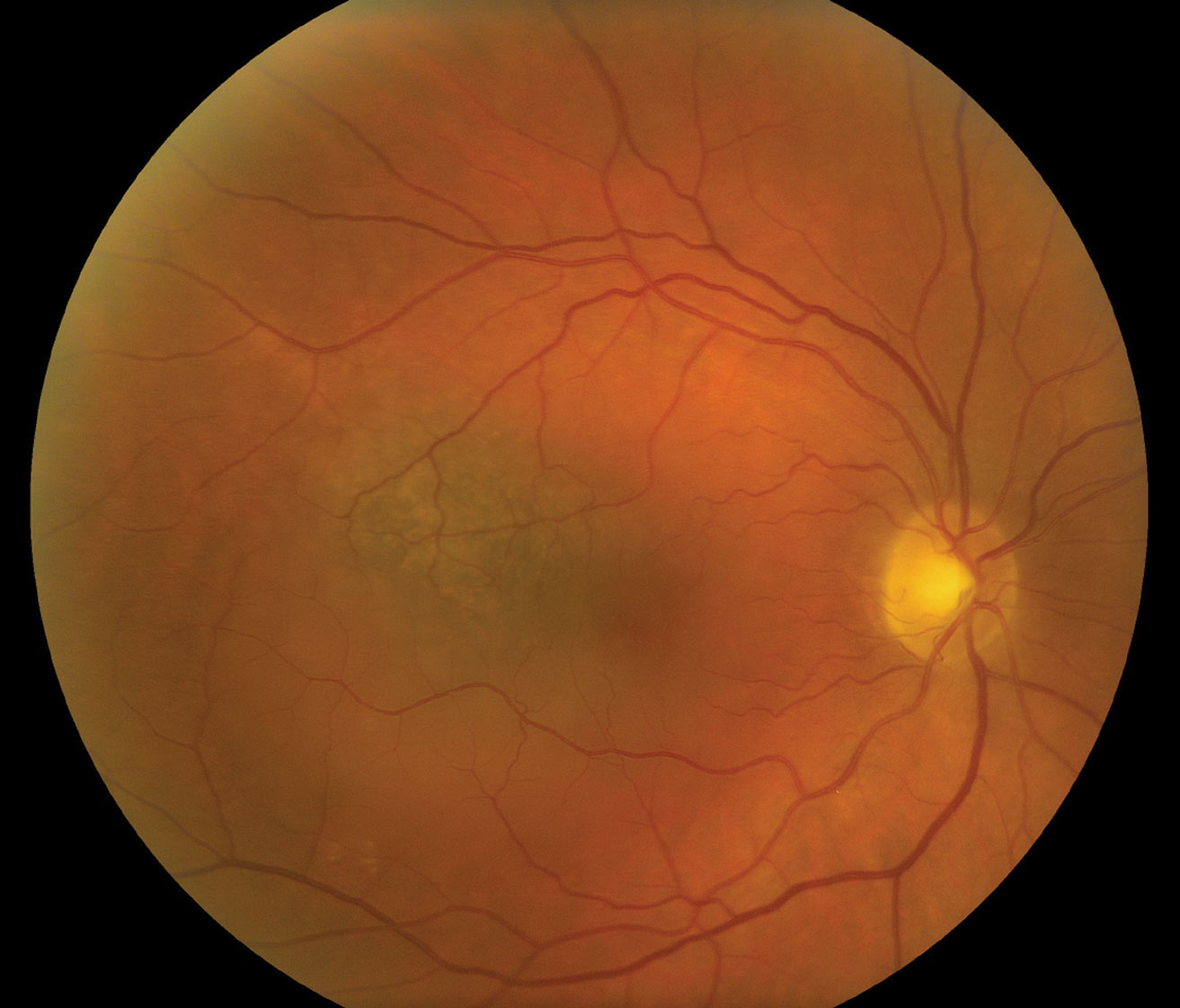

| This fundus photo shows a small, cream-colored choroidal melanoma within the posterior pole without overlying retinal detachment. Photo: Julie Rodman, OD and Desiree Wheeler, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

Discussion

We diagnosed his right eye with an exudative retinal detachment secondary to a choroidal melanoma. He was immediately referred to ocular oncology. The diagnosis was confirmed and found to be a secondary metastasis from primary lung adenocarcinoma.

The most common intraocular malignancies are metastatic in nature.4 They tend to present within the choroid in the form of choroidal melanoma in 88% of cases.4 Breast cancer is the most common cause of metastasis in women, and lung cancer in men.4-6 These conditions generally present with symptoms of flashes and floaters that result in a subsequent decrease in vision shortly after.4-6 Most metastatic growths are seen within the posterior pole due to its rich blood supply.4 They often appear as cream-colored lesions with an overlying serous retinal detachment and unilateral presentation.4-7

One study shows 66% of these patients had a previous systemic cancer diagnosis, leaving 34% of patients who experienced ocular manifestations initially.4 This means that, while still rare, these patients are likely walking into primary care optometry offices for initial examination, as was highlighted in this case study. While treatment options for orbital tumors over the years have been promising, it is controversial whether it is worthwhile to begin treatment in cases of metastasis from lung cancer.4,5 Once choroidal infiltration has occurred, the primary cancer is classed as stage IV.4 At this stage, a quick progression with poor prognosis is expected. Other sources state external beam radiation therapy or plaque brachytherapy can be advantageous.5

Dr. Kumar is a resident at Nova Southeastern University.

1. Stephenson M. Dysphotopsia: not just black and white. Rev Ophthalmol. 2017;24(11):52-65. 2. Hikichi T, Hirokawa H, Kado M, et al. Comparison of the prevalence of posterior vitreous detachment in whites and Japanese. Ophthalmic Surg. 1995;26(1):39-43. 3. Hollands H, Johnson D, Brox A, et al. Acute-onset floaters and flashes: is this patient at risk for retinal detachment? JAMA. 2009;302(20):2243-9. 4. Ergenc H, Onmez A, Oymak E, et al. Bilateral choroidal metastases from lung adenocarcinoma: a case report. Case Rep Oncol. 2016;9(3):530–6. 5. Hadden P, Damato B, McKay I. Bilateral uveal melanoma: A series of four cases. Eye. 2003;17:613–6. 6. Lampaki S, Kioumis I, Pitsiou G, et al. Lung cancer and eye metastases. Med Hypothoesis Discov Innov Ophthalmol. 2014;3(2):40-4. 7. Turaka K, Mashayekhi A, Shields C, et al. A case series of neuroendocrine (carcinoid) tumor metastasis to the orbit. Oman J Ophthalmol. 2011;4(3):125–8. 8. Singh P, Singh A. Choroidal melanoma. Oman J Ophthalmol. 2012;5(1):3-9. 9. Shields C, Mellen P, Morton S. American joint committee on cancer staging of uveal melanoma. Oman J Ophthalmol. 2013;6(2):116-8. |