|

What is the most valuable link to history? Is it the bulging file folders stuffed with yellowing texts lining the cabinets of the state hall? Conclusions reached by academic researchers? Until humanity unlocks the key to actually traveling to the past, perhaps the best resource for historical understanding is the people who lived it.

If nothing else, the editors of Review of Optometry have learned that the men and women who practiced in the 1960s, 1950s and even 1940s have been sitting on a goldmine of insight. The stories of their lives aren’t theirs alone. They are brush strokes in the grander image that makes up the history of optometric care. You too can access these treasure troves. It may not be as easy for you as it is for Andrew S. Gurwood, OD, whose own father, Irving Gurwood, OD, 74, taught at the Pennsylvania College of Optometry (PCO) starting in the early 1970s, when available diagnostic care was rudimentary at best. Between them, the two have some 80 years experience.

Dr. Gurwood spent this Father’s Day talking to someone who was not just a literal father to him, but one of a class of paternal figures to every OD in America today. Here, Dr. Irving Gurwood, 74, discusses the times, people and events that drove innovations in diagnostic technology, interviewed by his son, Andy.

Andrew: Before joining PCO, you served in the US Army. When did you get out of the service?

Irving: I finished my two-year commitment to the draft in 1968, then I went to two-year active reserve, and then a two-year inactive reserve.

So, you could numb the eye at that time?

In the service, we could.

What about outside the service?

Outside the service, we were not really allowed to use any diagnostic drugs. At the time I saw patients and we did mostly refractions and evaluations without the use of pharmaceuticals by using ophthalmoscopy.

What if you saw conjunctivitis? Would they let you suggest antibiotics?

No, the ophthalmologist would take over at that point.

Dropping Some KnowledgeIn 1934, Dr. Malcolm G. Hamrick wrote to The Optical Journal and Review to expound upon the virtues and value of the optometrist’s knowledge after being incensed by a newspaper ad (in those days this was referred to as professional business card) promoting optical wear rather than excellence in examination.

In 2016, as third-party payers have become the dominant force in examination fee/procedure reimbursement, the issue remains relevant. Government (Medicare and Medicaid) and private insurance companies continue to lower professional fee reimbursements annually as they attempt to trim fat from the bone. With fixed costs such as rent, utilities, phone, personnel, infrastructure and electronic medical records rising each year, practitioners are faced with three options to make up the shortfall: compete in the retail market for optical and non-optical devices (spectacles, low vision devices), see more patients or move into an inelastic specialty market by obtaining expert knowledge in a particular discipline, such as contact lenses, pediatrics/binocular vision, dry eye disease or sport/performance vision. As Dr. Hamrick realized in 1934, the value of having an optical dispensary cannot be denied. While the average third-party eye examination reimbursement today is less than $70, the average income seen on the sale of an optical device is far more profitable. Although the economic forces favor a culture that Dr. Hamrick recognized might limit the profession, I think we agree with his premise: it is clinical competence that permits all diseases—refractive, biologic and developmental—to be properly diagnosed and managed. Hamrick MG. Challenging medical claims for drops. Optical Journal-Review. 1934;61(23):16-7. |

How could you function in practice without diagnostic or therapeutic drugs when you had patients who needed them? Did you even have a slit lamp?

Yes. We learned to use a slit lamp in the service and we had limited slit lamps at the college. In my own office, I had a Neitz slit lamp. Just before I graduated, the Mackay-Marg tonometer came out, which did not require anesthesia of the cornea if you used a light touch.

I’m familiar with the Mackay-Marg. It gives a reading similar to today’s historometer, where you read a piece of graph paper to determine the pressure. In fact, I remember you had two in your office.

That’s correct.

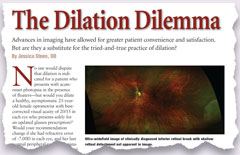

History Repeating ItselfIn 1934 and again in 1960 the concept of cycloplegic refraction was challenged in The Optical Journal-Review.1,2 Proponents recognized that cycloplegic refraction increased the accuracy of refraction while helping to eliminate patient subjectivity. Other advantages included uncovering “esophoric squint” brought on by high hyperopia; increased ability to discover pseudo myopia and other disorders of accommodation, which created false or variable refraction; and eliminate the unreliability seen in younger patients. Opponents argued that drops were unwelcomed by patients who would have to endure a “long period of blurred vision.” The drops sometimes created unwanted side effects and cycloplegic refraction was, as a rule, no more accurate than refraction without them. Today, we know that in ordinary circumstances cycloplegic refraction is not mandatory and yields no better refractive data than the dry. However, cycloplegic refraction is used to: (1) measure absolute refractive error before refractive surgery (2) rule out latent hyperopia and maximize prescribed plus in accommodative esotropes (3) relax patients’ convergence in cases of spasm of the near reflex (4) dispense a significant new hyperopic prescription (spectacles or contact lenses) using the tapered technique termed “cyclotherapy” (5) obtain reliable data where unreliable data had been obtained in the past The reply by Dr. Herschel Russell applies today: “When used intelligently and with a knowledge of the whys and wherefores, cycloplegics can be of a tremendous advantage to the capable refractionist.”2

|

Did you know Joe Toland?

I knew him. He was coming to the clinic on a one-day-a-week basis. I consider him one of the fathers of modern optometry. Irv Borish, OD, is certainly another. He had written textbooks. He was a good lecturer and a good writer, but the next phase of optometry—which brought us to diagnostic drugs—was primarily brought about by Joe Toland and his willingness to teach at the college and run its glaucoma clinic. Also, under his auspices, he would allow you to use an anesthetic to perform Shiotz tonometry. We hadn’t gotten the Goldmann tonometer, yet. You could do visual fields, too, but then you would refer to ophthalmology.

Internal StrugglesBetween 1968 and 1974, optometry began its renaissance, but not without some dissention. In 1968, Dr. S. Drucker’s impassioned Optical Journal-Review letter asks the profession to embrace its place in the medical science field as a “contributor to the store of knowledge in diagnosis and treatment by drugless methods” almost as if to say, ‘be proud of who you are and stop wanting to be something you’re not!’ Yet others pushed forward, advocating for a more active and curative profession. Drucker S. The need for reaffirming optometry’s philosophy on drugs. Optical Journal-Review. 1968;105(19):35-6. |

What about corneal scratches and foreign bodies? If you couldn’t use antibiotics and you couldn’t use cycloplegics, could you remove something from the cornea?

No. We were extremely limited.

Did you know Lou Catania, OD?

Lou Catania was a graduate of PCO, also a student of mine. Lou was able to use drugs and diagnostics and developed a tremendous reputation as a one of the first primary care practitioners. He joined PCO under President/Dean Norman Wallace, who brought PCO out of the dark ages. Lou was a dynamic speaker and writer. He also was extremely influential in the movement to move the profession forward.

Also, when Thomas Lewis, OD, was at the college, he and Tony DiStefano, OD, helped bring about PCO’s modern clinic, they called it the Eye Institute. They helped bring education all over the world, becoming a member of the World Health Organization. Dr. Lewis became a huge proponent of education. He established a solid endowment, which allowed the school to get advanced instrumentation, and they both helped bring about the change from PCO to Salus, recognizing that optometry could have an interdisciplinary approach with other health care professions.

When did the first states begin to get the ability to use diagnostic drugs for regular optometrists, not just the Veterans Administration or Armed Services optometrists?

In the early 1970s. As I remember, at that time, PCO was very active in developing a curriculum, along with many very fine teachers across the states. This is where Dr. Toland became very important, because he lectured and helped set up a CE program. At that time, he was a spokesman for optometry and appeared before many state boards and legislative bodies to influence the passage of diagnostic drug laws. In Pennsylvania—even though we were at the forefront of teaching others—we didn’t get the privilege to use diagnostic drugs until much later.

Man vs. MachineIn 1974, Walter Simpson, OD, wrote, “The entire field of glaucoma detection and diagnosis is making optometrists feel insecure and inadequate.” It must have been a cause of frustration for him to watch the tonometry revolution unfold along with the common introduction of techniques such as gonioscopy and tonography, and know these techniques could not be used by those in the “drugless” profession. As a measure of defense, he asked his colleagues, “is glaucoma not still the sum of optic disc changes with corresponding visual field changes? Is this not what ophthalmology has been professing for the last 20 years?” In this case, since the optometrist can use an ophthalmoscope to observe the optic disc and perimetry to measure the visual field, why would an optometrist be inadequate? He concluded, by evidence of his readings and by lectures he attended given by ophthalmologists, that these new “expensive” instruments had no evidenced-based data that supported their use over the conventional methods used to diagnose the disease (disc appearance and visual fields). In 2016, we understand there are multiple mechanisms and risk factors related to the formation of glaucoma, one of which is intraocular pressure. We got there through careful scrutiny of each of the disease’s parameters via evidence-based data where numerous elements of the eye and central nervous system have been evaluated by new “expensive” instruments (optical coherence tomography, pachymetry, histerometry, focal electroretinography, new tonometers). The goal has always been to understand the pathophysiology of the disease process, unlocking the first signs of conversion to the treatable form. Through the years, as the data came in, I’m sure Dr. Simpson recognized the benefits of the “new expensive instruments;” however, his big picture message is to question everything and verify with evidence-based data. Good advice. Simpson W. The glaucoma outrage. Optical Journal-Review. 1974;111(7):20-1. |

As I recall, Pennsylvania was one of the last in the late 1990s to get therapeutic drugs as well. And I remember, when I started optometry school, in 1985, only 28 states allowed therapeutics and only 48 allowed diagnostics.

What did the public think of the optometrist back in 1966, then midway in 1978, as compared to what the public thinks now?

I had the feeling the patients trusted me with their eyes and expected me to look after their vision and refer them if circumstances required additional care, such as treatment for glaucoma or referral for cataract removal. Remember, in those early days, there were no implanted lenses. Lenses were dissolved and taken out and consequently that’s when optometry really started to come into its own because, by that time, soft contact lenses were becoming available which helped the aphakic patient see without thick spectacles.

When did you first learn of soft contact lenses and how did you learn to fit them?

Well, I recall Bob Morrison, OD, from Harrisburg, Pa., was a respected optometrist and noted engineer in contact lens development and polymethyl methacrylate lenses. He was the first, I think, to bring over a Czechoslovakian lens material. He showed it to us and, of course, we were absolutely amazed. Of course, there were some vision problems with it and some fitting problems, but really the big breakthrough in soft lenses came when Bausch + Lomb developed their set of soft lenses with a fitting set and a sterilization method which, in those days, was saline with a small steamer (heat) type of unit. We went to CE programs set up by Bausch + Lomb at the college and other areas and we learned how to fit them.

Who in those days was laying the groundwork so that your practice could push forward?

Well, certainly organized optometry was very important. They were pushing for legislation, but basically it was the schools and associations of optometry and, I have to say, in my own mind: PCO was at the forefront of pushing for those types of legislation. As a matter of fact, A. Norman Haffner, OD—who was a pioneer—established a school up in New York and students from there were getting training at PCO, believe it or not!

What do you consider the greatest diagnostic advance that has helped you diagnose and manage disease? I would answer the OCT is the greatest advance that we’ve ever seen. I would have to say the binocular indirect ophthalmoscope would have to be up there. The Goldmann tonometer would be up there, too.

For me it was the 90D lens. I think OCT is also important in my mind, because it can bring into view the anatomic correlation of diseases of the optic nerve and retina … and now diseases under the retina. You can also get a printout that you can share.

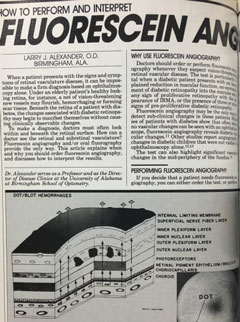

Standing The test of TimeIn 1988, the great Larry Alexander, OD, wrote an article in Review of Optometry on the merits of understanding, performing and interpreting sodium fluorescein angiography. The article predated his now famous textbook Primary Care of The Posterior Segment. It was succinct, accurate and contained photographs with schematic diagrams which crystalized the concepts of the paper. “Primary Care of The Posterior Segment” was the quintessential optometric retinal reference. It had both color and black and white photographs along with magnificent schematic illustrations, which clearly depicted the pathophysiology of each entity. It was well written, easy to understand and well referenced. The paper he wrote in 1988 is timeless; it still holds water and remains an accurate reference in 2016. Gosh, I miss him. Alexander L. How to perform and interpret fluorescein angiography. Review of Optometry. 1988;125(1):71-82. |

What about early fundus photography?

Certainly, that was a big help. The early cameras were expensive and clunky. They also used film. You might have to wait an entire month before you sent a roll to be developed. And if you didn’t keep good records when you shot the photos, you might not remember what or whom the picture was of. Many of us felt you didn’t have to go to that expense if you kept good records and you were able to use the 90D lens and the indirect ophthalmoscope to find and then draw (with colored pencils) what you saw. Today, the modern day slit lamp and its auxiliary lenses really permit good views; all of these tools help in the diagnosis of things like hypertension-related issues like vein occlusion, emboli, artery occlusion and diabetic retinopathy.

You couldn’t do a contact three mirror or gonio evaluation, because you couldn’t numb the eye to get a get a gonio prism on it.

Actually, at PCO, we did develop a sneaky way to do gonio, by putting a soft lens on the eye first and then putting the gonio on the soft lens.

What can optometry do to improve diagnostic capabilities in the future?

I just think, for optometry to better succeed and have a better footing with the public and the medical profession, we need to keep current. We need to fight harder than the average bear. We’re a young profession—we’ve really only been around for 60 or 70 years, and since the 1980s, these last 30 years, we’re just coming into our own with diagnostics and pharmaceuticals. Our teaching, certainly, is bringing more non-ODs into the teaching realm where, before, one of the criticisms was that we only had ODs teaching ODs. Now, we have people in PhD roles, MDs, retina and glaucoma specialists. We’re coming into our own.

I think we always need to be on the cutting edge with continuing education. It’s a good thing that we came up with CE and mandatory number of hours per two years in Pennsylvania and other states to keep our brethren current in the field. And then put those things to use! We’ve got to put it to use. My concern is, we teach students to be very fine practitioners and they walk out and go into situations where they’re not using the full scope of their knowledge.

My dream would be to see optometry to go the way of dentistry and podiatry. Dentists now have a “DMD” degree. Podiatrists have a “DPM.” Even veterinarians have “VMD.” I would like to see the birth of the “OMD,” optometric medical doctor. We might have to partner with medicine and dovetail our curriculum and residencies with theirs, but this would permit us to get the residency training nationwide to practice at the level we’re taught in our schools. It’d go a long way to better serving the public.