|

Q:

I have an emergency walk-in patient who came into our practice complaining of a foreign body sensation after cooking. Upon slit-lamp examination, I found no foreign body but, instead, a white spot on the cornea. What could it be?

A:

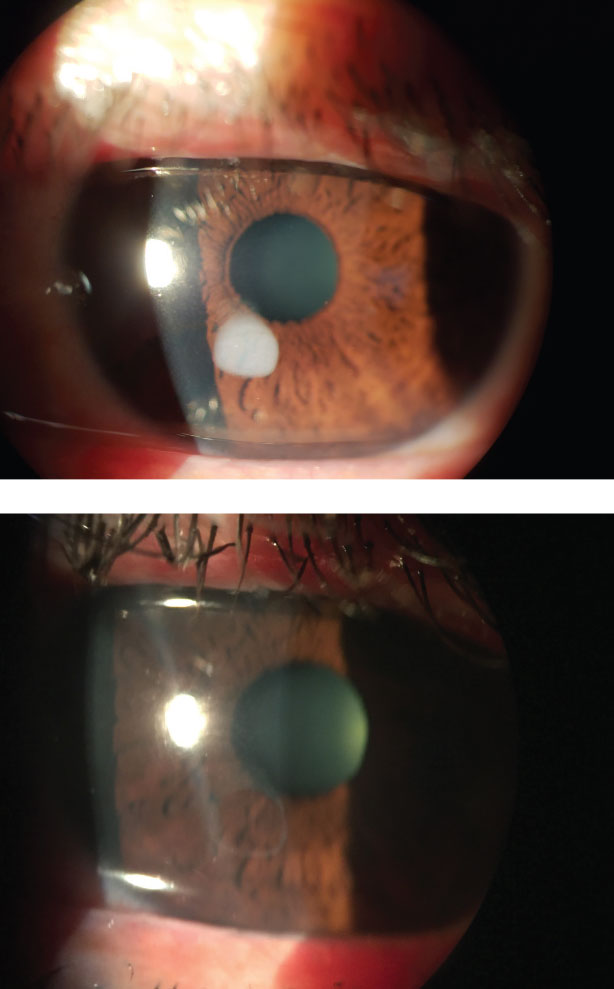

As with all emergency patients, the most essential part of your exam is a careful case history. “Asking detailed questions is paramount,” says Kirsten Weitzel, a fourth year optometry extern working with Dr. Ajamian at Omni Eye Services of Atlanta. Her patient that day, a 42-year-old bakery worker, stated that he was cooking hot caramel in a saucepan under medium heat when some of it splattered into his eye. Irrigation with water helped, but he still noticed a white spot on his eye when looking in the mirror (Figure 1). The patient stated the eye was mildly irritated and sensitive to light. His unaided vision was 20/20 OD and OS.

|

| Figs. 1 and 2. Focal caramel burn and eye post-debridement. |

First-degree Examination

Ms. Weitzel advises, in any case of a suspected foreign body, to get the big picture by having the patient look up, down, left and right, and then evert the lids and make sure nothing else is hiding. Next, perform a complete corneal and anterior chamber evaluation.

After a thorough examination, the only noteworthy finding was the spot on the epithelium. The list of differentials included subepithelial infiltrate, corneal ulcer, corneal foreign body and thermal burn.

“While it is the clinician’s job to consider every potential diagnosis, typically the simplest answer is most often the correct one,” says Ms. Weitzel. Given the history and the exam, the team diagnosed their patient with a minor corneal thermal burn.

These burns have many causes, but each culprit will have a slightly different presentation. The most common causes of thermal burns include: firework explosions, curling irons, cooking oil, boiling water/steam, molten metals/plastics and, of course, hot caramel!

Corneal thermal burns do not look like a corneal abrasion or foreign body, as the epithelium is typically not missing. Epithelial burns tend to appear as white, flat lesions, where the affected tissue is necrotic. The patient’s symptoms will vary depending on the amount of corneal involvement and the extent of the burn.

Second-degree Management

Determine the depth of the burn, Ms. Weitzel advises. This indicates the amount of scarring, if any, that will occur after the cornea is fully healed.

The first step in thermal burn treatment is to debride the necrotic epithelium. Anesthetize the eye and run a lubricated cotton swab over the necrotic tissue; the involved epithelium should come off easily, with well-defined borders leaving a clean defect. A foreign body spud can be used but could be more time consuming; however, in the case of a small focal burn, the spud is too large for the targeted tissue.

During initial management, the main goal is to support epithelial healing, which involves heavy lubrication and prophylactic antibiotic therapy. If the patient is uncomfortable or light sensitive, a cycloplegic or oral NSAID can be prescribed. If the burn is more involved (i.e., more corneal layers affected) or if the burn is located on the visual axis, an amniotic membrane may be considered.

“This patient’s burn was not located in the visual axis and the affected area was superficial,” Ms. Weitzel pointed out. After debridement, the patient was left with a small epithelial defect (Figure 2) that healed within a day.