|

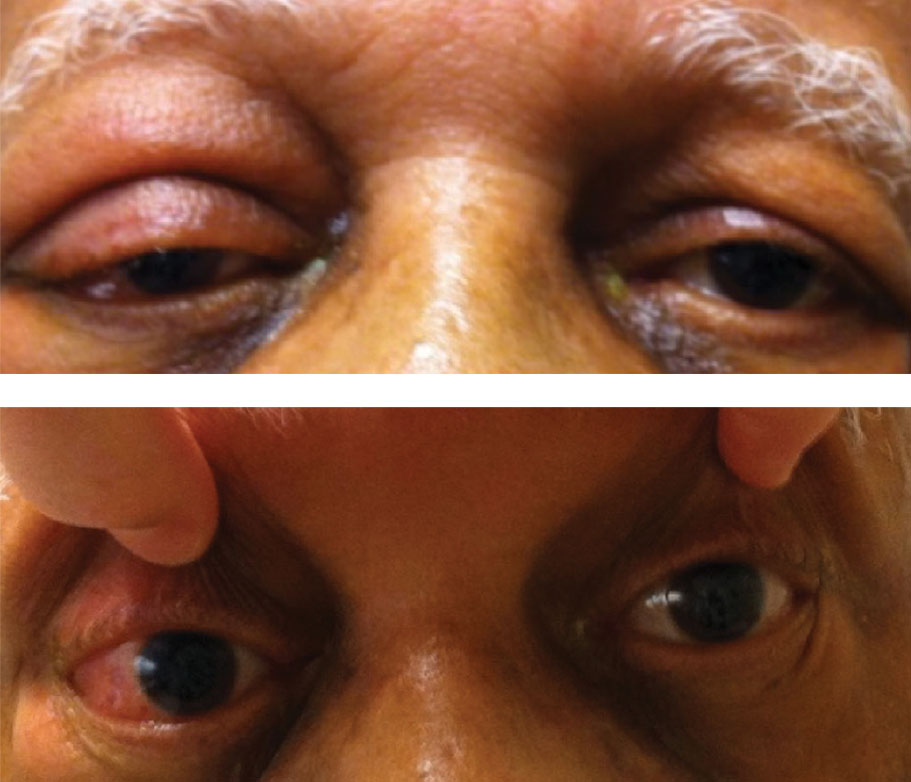

A 69-year-old African-American male presented emergently with painless, marked swelling and redness of the right eye (Figure 1). His history was positive for longstanding hypertension and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL), which he said has been in remission for eight years.

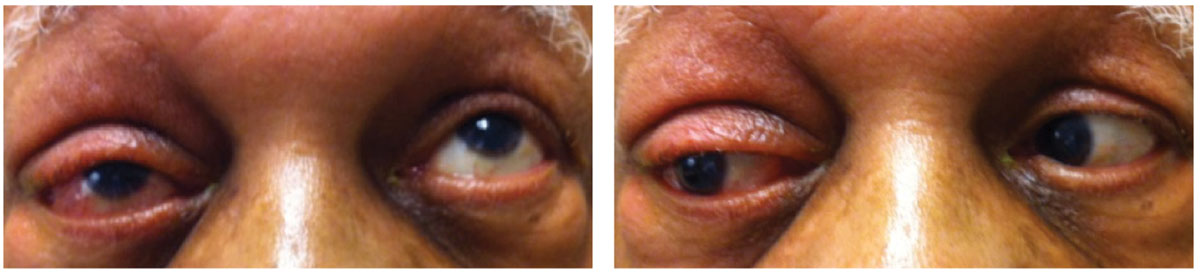

The patient’s pinhole visual acuities measured 20/30 OD and 20/30 OS. No afferent pupillary defect was present. Extraocular movement was limited in the right eye, which appeared proptotic (Figure 2). Exophthalmometer findings measured 25mm OD and 21mm OS with a base of 110mm. Given these findings, his differential diagnosis included:

- Orbital tumor

- Idiopathic orbital inflammatory pseudotumor

- Thyroid eye disease

- Preseptal/orbital cellulitis

- Orbital mucocele

- Dacryoadenitis

We immediately ordered blood work to test blood urea nitrogen and creatinine followed by an MRI of the brain and orbits with contrast. The MRI revealed a thickened mass located in the right lacrimal gland. The patient underwent an anterior orbitotomy and a biopsy of the mass, which revealed a malignant neoplasm consistent with mature B-cell lymphoma.

|

| Fig. 1. This patient has marked chemosis and hyperemia in his proptotic right eye. Click image to enlarge. |

Discussion

Lymphocytes—white blood cells—are one of the body’s main types of immune cells. They are produced in the bone marrow and found in blood and lymph tissue. The two most common kinds are B-lymphocytes (B-cells) and T-lymphocytes (T-cells). B-cells make antibodies, and T-cells kill tumor cells and control immune responses.1

Malignant lymphomas are neoplasms derived from clonal (i.e., unicellular in origin) proliferations of lymphocytes. More than 70 different types of lymphoma exist, ranging from indolent (slow growing) to highly aggressive.1 Lymphoma may be primary or secondary to systemic disease.1,2 While lymphoma can have sight-threatening implications, it is often treatable when caught early and treated aggressively.

Neoplastic Disease Refresher

The American Cancer Society defines cancer (or carcinoma) as a group of diseases characterized by uncontrolled cell growth and abnormal cell spread.3 Cancer has the capacity to invade surrounding normal tissue, metastasize and kill the host. Neoplasia is the process of abnormal growth that starts from a single altered cell.4

Uncontrolled proliferation happens when genes controlling cellular growth no longer function properly. The lymphocytes then grow uncontrollably, multiply abnormally or live longer than they should.2,6 This is when lymphoma occurs.

Benign neoplasms cannot spread by invasion or metastasis—they only grow locally. Malignant neoplasms, on the other hand, can.4,5 These cells must first develop the capacity to cause invasive destruction before they can metastasize.5,6 By definition, the term cancer applies only to malignant tumors.

Lymphoma and the Eye

Lymphoma is categorized as either NHL or Hodgkin’s lymphoma (HL). In the United States, the lifetime risks of NHL and HL are 2.1% and 0.2%, respectively.1,2 B cell lymphoma is far more common than T-cell lymphoma and accounts for about 80% of all NHL cases.2 Lymphomas involving the eye can be divided into three broad groups: uveal, vitreoretinal and ocular adnexal.2,7 Each type differs in its clinical presentation, diagnosis, treatment and outcome.

A lymphoma located inside the eye that does not involve extraocular tissue is termed intraocular. Almost all intraocular lymphomas are of the NHL type, and the vast majority are of B-cell origin. Intraocular lymphoma has two distinct forms: one that arises inside the central nervous system (CNS), including the retina, and one that arises outside the CNS, with intraocular metastasis.2,7 The former, also called primary CNS lymphoma (PCNSL), is far more prevalent than the latter and is well documented.2 PCNSL involves the retina, vitreous or optic nerve head. Ocular symptoms include blurred vision, floaters and decreased visual acuity. Primary intraocular lymphoma, a subset of PCNSL, may present with or without simultaneous CNS involvement.2,7

Ocular adnexal lymphomas may present on or within the lids, conjunctiva, orbit, lacrimal gland or lacrimal sac. Lymphoma is the most prevalent orbital neoplasm in adults aged 60 or older.8 Lacrimal gland lymphoma is relatively rare, representing 7% to 26% of all ocular adnexal lymphomas.2,7,9

|

| Fig. 2. Here, you can see our patient’s slight limitation on extraocular movement. Click image to enlarge. |

Diagnosis and Management

As our case highlights, the list of differential diagnoses for an orbital mass lesion is long. Orbital neoplasms are categorized based on location and histologic type. Optometrists must provide a thorough ophthalmic evaluation for patients with suspicious presentations, including appropriate serologic and radiologic testing, to narrow down the diagnosis. Neuroimaging features of these lesions often reflect their tissue composition. Comanagement with oculoplastics (for biopsies) and oncology is prudent.

The reported case is unusual in that the lymphoma developed in the lacrimal gland after a period of NHL remission. Researchers have documented orbital and adnexal NHL in relapses of previously diagnosed lymphomas.2,7,9,10

Although the orbit is rarely a secondary site of lymphoma dissemination, clinicians should immediately investigate if a patient with an established NHL diagnosis develops ophthalmic or orbital symptoms. The typical presentation of adnexal lymphoproliferative disease with orbital involvement includes a painless, palpable mass lesion, swelling, ptosis, proptosis, diplopia or a lid edema. Adnexal structure involvement in systemic NHL may occur at any time during the course of the disease, including as a relapse site.2,9

Based on the neuroimaging, incisional biopsy of the involved structures should be performed to reveal the tumor type through pathology testing. In our patient’s case, the lacrimal gland was the site biopsied. In addition, serology and molecular testing for certain genes and proteins may help determine disease extent. Liver, pulmonary and kidney function testing, along with echocardiography, should also be obtained to investigate for lymphoma at other sites and to determine the patient’s status for treatment options.2,7,9

Local radiation may be pursued, with close monitoring for gradual resolution of signs and symptoms. Systemic chemotherapy or immunotherapy in combination with local radiation can achieve good results in secondary orbital NHL.2,9 Treatment options for intraocular lymphoma include ocular radiotherapy and intraocular chemotherapy.

In this case, we prescribed a non-preserved tear supplement every four hours and a gel formulation before bed to protect the ocular surface. We referred him for treatment, which will likely include systemic chemotherapy or immunotherapy in combination with local radiation.

More than half of NHL patients are 65 or older when they are diagnosed.11 As the population continues to live longer, we will likely see an increase in such cases, stressing the importance of early intervention and appropriate management.

| 1. Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, et al.,eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues, revised. 4th ed. International Agency for Research on Cancer; Lyon: 2017. 2. Couceiro R, Proença H, Pinto F, et al. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma with relapses in the lacrimal glands. GMS Ophthalmol Cases. 2015;5:Doc04. 3. American Cancer Society. What is cancer? www.cancer.org/cancer/cancer-basics/what-is-cancer.html. Accessed October 8, 2019. 4. National Cancer Institute. Cancer as a disease. training.seer.cancer.gov/disease. Accessed October 8, 2019. 5. Cornett PA, Dea TO. Cancer. In: SJ McPhee, MA Papadakis, eds. 2010 Current Medical Diagnosis and Treatment. 49th ed. New York: McGraw Hill Medical; 2009:1450-1511. 6. Weinberg RA. The Biology of Cancer. New York: Garland Science; 2006:ch.1-5.5. 7. Farmer JP, Lamba M, Lamba WR, et al. Lymphoproliferative lesions of the lacrimal gland: clinicopathological, immunohistochemical and molecular genetic analysis. Can J Ophthalmol. 2005;40(2):151-60. 8. Tailor TD , Gupta D, Dalley RW, et al. Orbital neoplasms in adults: clinical, radiologic, and pathologic review. Radiographics. 2013 Oct;33(6):1739-58. 9. Tang LJ, Gu CL, Zhang P. Intraocular lymphoma. Int J Ophthalmol. 2017;10(8):1301-7. 10. Shields JA, Shields CL, Scartozzi R. Survey of 1264 patients with orbital tumors and simulating lesions: the 2002 Montgomery Lecture, part 1. Ophthalmology. 2004;111(5):997-1008. 11. Chihara D, Nastoupil LJ, Williams JN, et al. New insights into the epidemiology of non-Hodgkin lymphoma and implications for therapy. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2015;15(5):531-44. |