|

An 86-year-old Hispanic female presented to our office with complaints of blurred vision of the right eye for the past two months. She denied flashes, floaters, double vision or eye pain. Her medical history was remarkable for tachycardia, for which she was being treated with propranolol. She reported no personal or familial history of cancer, including ocular and cutaneous melanoma.

Evaluation

On examination, her best-corrected visual acuity was 20/200 OD and 20/20 OS. Her right eye’s confrontation visual fields were constricted nasally and were full-to-careful finger counting in the left. Ocular motility testing results were normal and the pupils were equally round and reactive to light without an afferent pupillary defect.

The anterior segment was significant for meibomian gland dysfunction and confluent corneal guttae of both eyes without corneal edema. The anterior chambers were deep with no evidence of cell or flare. She had posterior chamber intraocular lens implants with 2+ posterior capsular opacification of the right lens and open posterior capsule of the left lens. Her intraocular pressures were 17mm Hg OD and 20mm Hg OS.

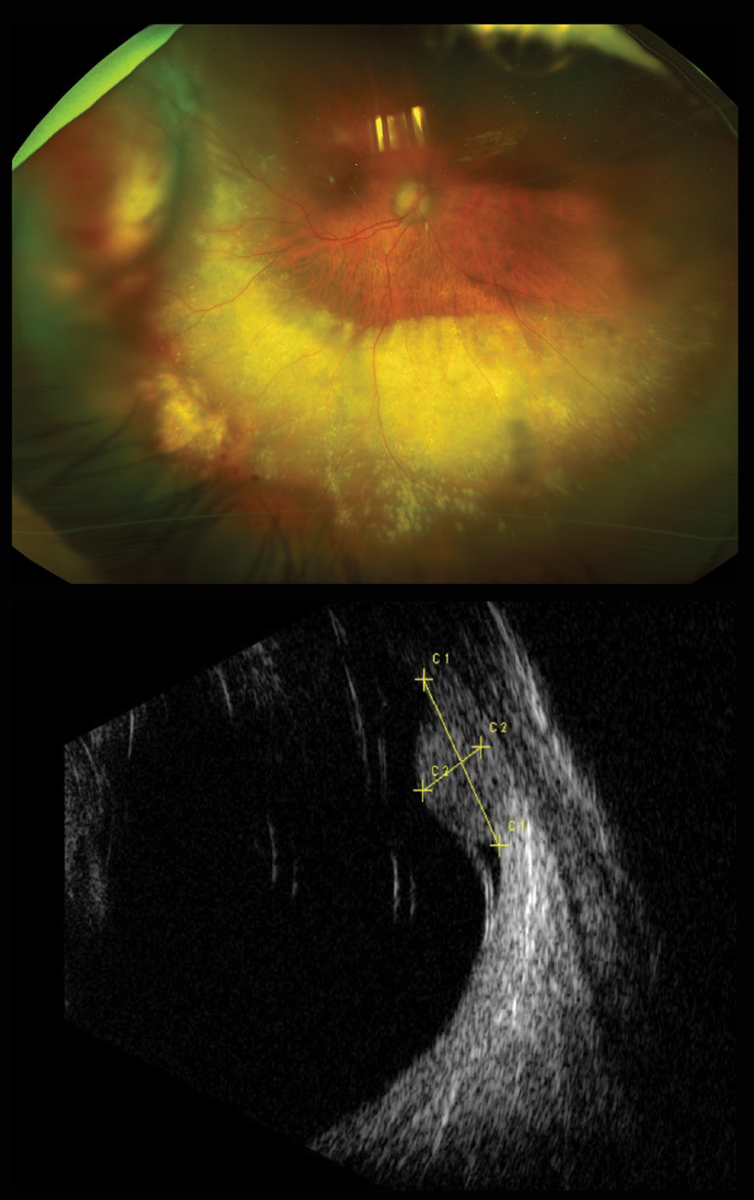

On dilated fundus exam, the vitreous was clear with no cells. The optic nerves appeared pink and healthy with good rim coloration and perfusion in both eyes. A reddish subretinal mass was visible in the far temporal periphery in the right eye at 9 o’clock associated with overlying subretinal hemorrhage and a shallow inferior exudative retinal detachment with subretinal lipid exudation (Figure 1). The peripheral retinal exam of the left eye was normal.

Additional Testing

Echography was performed of the right eye and showed a broad, non-vascularized, medium-high reflective lesion in the temporal quadrants straddling the equator anteriorly and posteriorly. The maximum thickness of the lesion was on the anterior side of the equator at 9 o’clock measuring 3.1mm. A shallow retinal detachment is noted over and adjacent the lesion (Figure 2).

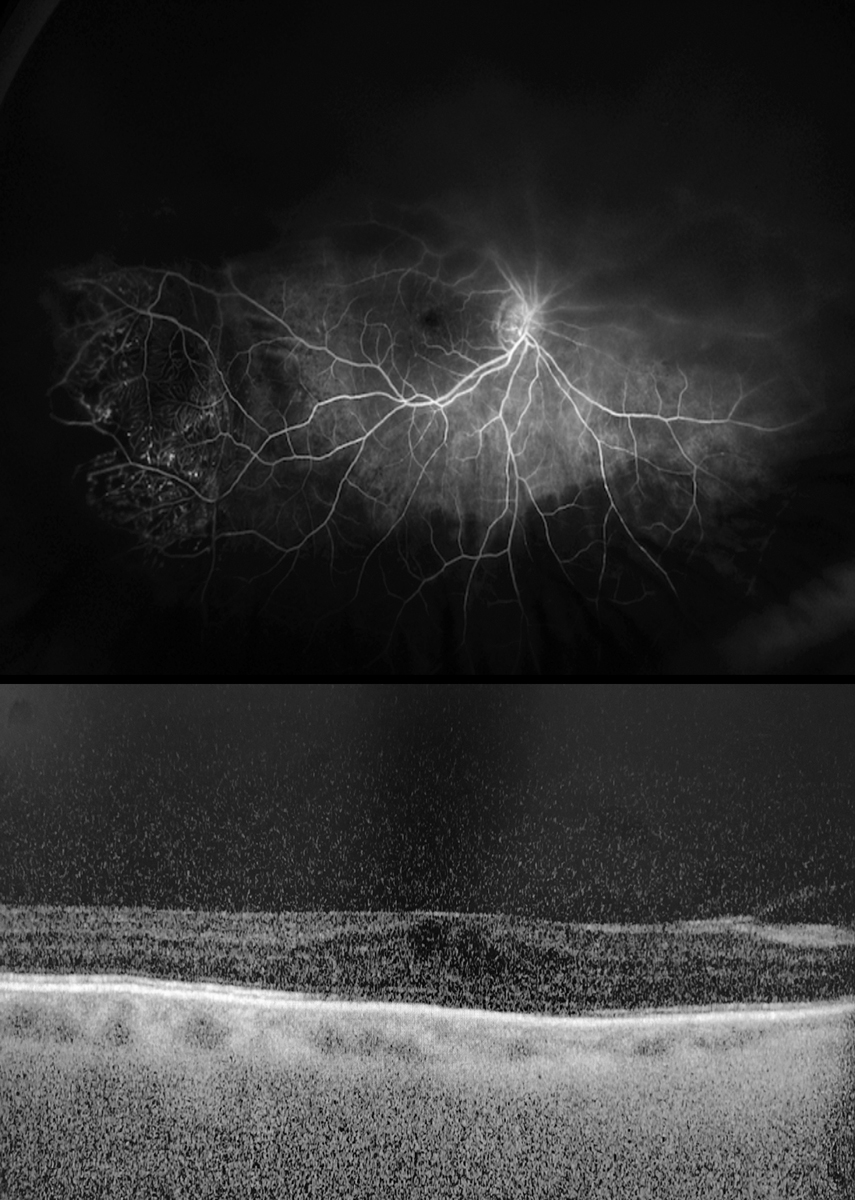

Fluorescein angiography (FA) of the right eye showed early phase perifoveal petaloid leakage, temporal far peripheral aneurysmal dilatations with telangiectatic vessels and evidence of late leakage (Figure 3). The left eye was normal.

SD-OCT of the right eye showed cystoid macular edema, vitreomacular traction and blunting of the foveal contour (Figure 4). The left was normal.

|

Figs 1 and 2. At top, our patient’s right eye, seen in widefield image, has an elevated lesion. Below, the B-scan through the lesion below also shows its thickness and the overlying retinal detachment. Click image to enlarge. |

Take the Retina Quiz

1. What is the likely diagnosis?

a. Amelanotic choroidal melanoma.

b. Vasoproliferative tumor.

c. Retinal capillary hemangioblastoma.

d. Choroidal osteoma.

2. What genetic conditions are associated with this lesion?

a. Tuberous sclerosis.

b. Neurofibromatosis.

c. Von-Hippel Lindau.

d. None of the above.

3. Which statement best describes the histology of this lesion?

a. Reactive astrocytic glial proliferation.

b. Composed of capillary-like vascular channels between large foamy cells.

c. Benign ossifying choroidal tumor.

d. Mixture of spindle cells and epithelioid cells.

4. Which if the following pre-existing ocular conditions are associated with development of this lesion?

a. Retinitis pigmentosa.

b. Coats’ disease.

c. Previous retinal detachment repair.

d. All of the above.

For answers, see below.

Diagnosis

We can clearly see temporally in the right eye an elevated mass with a significant amount of exudation extending inferiorly circumferentially. One of the biggest concerns was the possibility of a choroidal melanoma, but aside from the elevation, the clinical picture didn’t really fit a melanoma diagnosis. In addition, the ultrasound showed the lesion to have medium-to-high reflectivity, which is not typical for a choroidal melanoma, which usually exhibits low-to-medium reflectivity.

So, we must consider other causes, and the massive amount of exudation should be an important clue. The exudation combined with the FA, which shows significant aneurysmal vascular changes in the periphery, points to Coats’ disease.

Coats’ disease is an idiopathic vascular anomaly characterized by aneurismal dilations and telangiectasia of the retinal vessels.1-2 It’s often unilateral and most (more than 90%) cases occur in males between the first and second decade of life.1-2

|

Figs. 3 and 4. In the above fluorescein angiogram, the patient’s aneurysmal dilations and leakage are visible. Below is an OCT. Click image to enlarge. |

Our patient is female (and much older), so this would be extremely unusual. The retinal capillaries tend to be most affected, but changes can also be seen in the major retinal vessels. These vessels become incompetent and leak fluid in the form of exudate. The hallmark of this condition is an exudative retinopathy. The extent of involvement and degree of severity can be variable.

That doesn’t completely explain why there is a large elevated mass. Putting this all together, our patient likely has a vasoproliferative tumor as a secondary complication of Coats’ disease. Less likely possibilities include peripheral exudative hemorrhagic chorioretinopathy (PEHCR), amelanotic choroidal melanoma, retinal hemangioblastoma, choroidal hemangioma and choroidal metastatic tumors.

Discussion

Vasoproliferative tumors appear as ill-defined reddish-yellowish globular masses, most frequently involving the inferotemporal periphery. These tumors are difficult to visualize ophthalmoscopically and are easily confused with other choroidal tumors or eccentric disciform lesions.

Vasoproliferative tumors are classified into two categories: idiopathic or secondary to pre-existing ocular diseases. Histology demonstrates that these tumors are comprised of a preponderance of reactive astrocytic cells, as opposed to vascular proliferation, despite the nomenclature.3 The terms reactionary retinal glioangiosis and retinal reactive astrocytic tumor reflect the histopathology.

These tumors are generally thought to be reactive lesions that arise in response to chronic chorioretinal injury. The most common conditions leading to secondary vasoproliferative tumors include retinitis pigmentosa, intermediate uveitis, Coats’ disease and previous retinal detachment repair.4

Vasoproliferative tumors themselves are benign; however, they can produce significant intraretinal and subretinal exudation, exudative retinal detachment, cystoid macular edema (CME), epiretinal membrane and hemorrhage leading to visual symptoms, including floaters, distortion, photopsia and poor vision. Anterior segment complications related to vasoproliferative tumors are rarely reported.4

Management of these lesions depends on the tumor size, location, amount of exudative retinopathy and patients’ symptoms. Close observation to watch for growth is recommended for small peripheral lesions with minimal exudation.5 These lesions are typically seen in the setting of an epiretinal membrane and vitreoretinal traction, and therefore a pars plana vitrectomy and membrane peel may be indicated.

Intravitreal anti-VEGF injection and intravitreal steroid injections may be used to manage the exudative retinopathy and macular edema.

Cryotherapy, brachytherapy and argon laser photocoagulation are the mainstay treatments used for tumor regression.6

Our patient had developed CME because of the massive amount of exudation. We recommended a pars plana vitrectomy with a membrane peel. She also had an intravitreal injection of an anti-VEGF medication on the initial visit and an intravitreal injection of Triesence (triamcinolone acetonide, Novartis) at the time of surgery. We are also considering performing low-energy, long-duration argon laser to the subretinal lesion and abnormal overlying vasculature.

Dr. Nguyen is currently an OD Resident at Bascom Palmer Eye Institute in Miami.

1. Do D, Haller J. Coats’ Disease. In: Ryan SJ. Retina, vol. II: Medical retina. 4th edition St. Louis: Mosby; 2006:1417-23. 2. Gass J. Stereoscopic atlas of macular disease: diagnosis and treatment. 4th edition. St Louis: Mosby; 1997:494-582. 3. Irvine F, O’Donnell N, Kemp E, Lee WR. Retinal vasoproliferative tumors: surgical management and histological findings. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118(4):563-9. 4. Shields C, Kaliki S, Al-Dahmash S, et al. Retinal vasoproliferative tumors: comparative clinical features of primary vs secondary tumors in 334 cases. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013;131(3):328-34. 5. McCabe C, Mieler W. Six-year follow-up of an idiopathic retinal vasoproliferative tumor. Arch Ophthalmol. 1996;114(5):617. 6. Krivosic V. Management of idiopathic retinal vasoproliferative tumors by slit-lamp laser or endolaser photocoagulation. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014;158(1):154-61. |

Retina Quiz Answers:

1) b; 2) d; 3) a; 4) d.