|

Q:

I recently started fitting scleral lenses on irregular corneas and have run into a few cases where I’m not sure what role flexure is playing when a patient experiences less-than-ideal vision. Sometimes, even a careful spherocylindrical over-refraction fails to improve vision significantly. Could the poor vision be due to another cause?

A:

Over the last several years, scleral lenses have proven to be life-changing devices for countless patients who need the protection they afford the corneal and limbal surfaces or who need gas permeable (GP) optics but can’t tolerate GP lenses, according to Jason Jedlicka, OD, associate professor at the Indiana University School of Optometry and chief of the school’s Cornea and Contact Lens Service. However, Dr. Jedlicka notes that visual acuity can be reduced with scleral lens wear for several reasons, including residual astigmatism due to lens flexure.

|

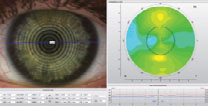

| Topography over a scleral lens shows 1.7D of lens flexure. Click image to enlarge. |

The Root of the Problem

Lens flexure occurs when the shape of the corneal surface is regularly toric to the point that the lens bends when it lands, allowing some of the shape of the eye to be manifest in the shape of the lens. Dr. Jedlicka recommends performing keratometry or topography to evaluate lens shape on eye. If the lens is flexing, the results will indicate astigmatism. Sclerals do not land on the cornea, so lens flexure only occurs when there is regular scleral toricity. Additionally, scleral shape does not always correlate with corneal shape, so you cannot necessarily predict flexure based on corneal toricity, he cautions.

Studies show that 30% of eyes demonstrate regular toricity of at least 300µm and 40% demonstrate asymmetric toricity, which means the potential for flexure exists in a number of patients.1 Dr. Jedlicka suggests the best way to fit scleral lenses to reduce the risk of flexure is to make sure the lens is in optimal alignment with the sclera. If the lens aligns with the sclera, be it toric or not, it should not flex.

If your lens fit is optimal but your refraction is still indicating regular astigmatism, Dr. Jedlicka says the only way to pinpoint the source is with keratometry or topography. If either yields astigmatism and it matches the refraction, he notes that the diagnosis is flexure. He recommends re-evaluating your fit and seeing if you can add toricity to the haptic to improve alignment. If this is not possible, he notes that increasing center thickness, while being mindful of corneal oxygen demand, can help. If this doesn’t solve the problem, he says additional front surface toricity may offset the flexure. He warns that this can impact lens thickness, and, as flexure is not always consistent, covering it up with front surface cylinder may not be the best visual solution.

Not all cases of reduced acuity with a scleral lens are due to flexure or residual astigmatism, so other factors must be ruled out. Many irregular cornea patients have higher-order aberrations due to the back surface of their cornea—such as coma in cases of keratoconus—and GP and scleral lenses can do little to address that, Dr. Jedlicka says. He suggests performing retinoscopy to detect irregular optics that persist through a scleral and help determine if this is the problem. Poor wettability, which can happen at any time, and debris in the fluid reservoir, which happens with time, can also reduce acuity.

Helping scleral lens wearers attain the best possible vision means taking all factors into account. With the increased ease of prescribing toric haptics and performing scleral topography to help determine scleral shape and haptic necessity, avoiding or managing flexure should fall well within our wheelhouse.

1. DeNaeyer G, Sanders D, van der Worp E, et al. Qualitative assessment of scleral shape patterns using a new wide field ocular surface elevation topographer. J Contact Lens Resear Sci. 2017;1(1):e12-22. |