| |

| The SLT procedure tends to be effective in most patients—approximately 80% to 90% of patients will have an effective outcome. The more pigment the patient has in the trabecular meshwork, the better the likelihood of success. |

Laser therapy in glaucoma, particularly selective laser trabeculoplasty (SLT), is moving closer to being embraced as a first-line treatment. This installment of our ongoing “Essential Procedures” print-and-video series explains just how to perform it.

We’ve heard plenty of excuses from noncompliant glaucoma patients in our practices:

- “I am really going to struggle taking my glaucoma drops.”

- “I can’t afford the medications.”

- “I get more of the drop on my cheek than in my eye.”

- “I get the drops in three or four days per week.”

Compliance with topical medications is one of the biggest issues doctors face when treating patients with primary open angle glaucoma (POAG). In the United States, the standard of care for the past few decades has been to follow a straightforward tier system when selecting the right glaucoma treatment: drops first, laser second, surgery third. Treatment should always be tailored patient-by-patient, based on factors such as disease severity, the patient’s age and testing results. But the aforementioned tiered-treatment protocol has largely been the standard for years. In many instances, doctors will try two or three drops before moving up to the second treatment tier. Recent evidence is challenging this thinking and forcing treating optometrists and ophthalmologists to ask themselves: when should I consider laser?1 It’s an intriguing question, especially considering the fact that eye care providers in many European countries have long considered SLT a first-line therapy.2

| |

| A critical element of laser therapy is to prepare the eye by performing a gonioscopy exam first to confirm that the patient’s eye provides enough room to perform the procedure and the trabecular meshwork is clearly visible. It will also help to determine the amount of pigment in the angle, which will dictate the energy setting. |

Laser History

SLT, introduced in 2001, is an improvement in the mechanism of action over its predecessor, argon laser trabeculoplasty. ALT uses laser energy to cause a thermal, or coagulative, burn upon the trabecular meshwork (TM), which mechanically opens up adjacent areas (a so-called “mechanical effect”). SLT uses a shorter duration of laser energy than ALT to cause a sub-lethal stress reaction in the TM cells, which causes inflammatory cells to travel to the meshwork and clean out the cellular debris, enhancing aqueous outflow (a so-called “biologic effect”).3 The structural damage to the TM is far less in SLT compared with ALT, and this may be one factor in its more favorable repeatability.4

The “selective” in SLT is named so because the procedure selectively targets the melanin-containing cells in the TM, which absorb the laser energy and cause the desired tissue changes to enhance outflow. To that effect, the more pigmented the TM, the more effective the laser.

The effectiveness of SLT depends on numerous factors. On average, 80% to 90% of patients will experience intraocular pressure (IOP) lowering of 15% to 30%.3 In my clinical experience, when patients present with heavy pigment in the TM, success rate is even higher due to all of the pigment that the laser can select. Patients with higher initial IOPs and no prior treatment often have more significant IOP reduction. This effect is similar to topical glaucoma drops, which have a greater IOP-lowering effect the first time (25% to 35%), compared with the later drops (which may only lower IOP 10% to 15%).5

| |

| Because SLT creates no pits, craters or blanching of the tissue, doctors performing the procedure won’t be able to rely on visual landmarks to show them where they started. Always start in the same place to ensure you remember where the first laser was fired. |

The area of treatment often will significantly affect the IOP lowering effect. Scientific studies and clinical experience has shown that a larger area of the angle often packs a much bigger punch in terms of IOP lowering effect than if a smaller amount of the angle is treated.6

Indications and Contraindications

Indications for performing SLT are numerous. The five most common entities for which you may consider SLT are:

- POAG.

- Low-tension glaucoma.

- Pigment dispersion syndrome/glaucoma.

- Pseudoexfoliative glaucoma.

- Ocular hypertension.

Even in these cases, the standard of care remains one or two glaucoma drops first and then, once the patient has reached maximum medical therapy, consider laser. However, this view is changing and many are now shifting laser to the top of the list in their treatment approaches, due to numerous studies, including the SLT/MED study, which shows a favorable comparison between SLT and prostaglandin therapy for first-line treatment.1,2,7

SLT is contraindicated for patients who have an angle that is not open enough to clearly visualize the TM. Evidence of any secondary glaucoma, such as neovascular, inflammatory, angle recession or congenital glaucoma, are also either absolute or relative contraindications, depending on the case. Complete failure of a prior laser trabeculoplasty, either ALT or SLT, should also give reason for pause when considering an additional SLT.

| |

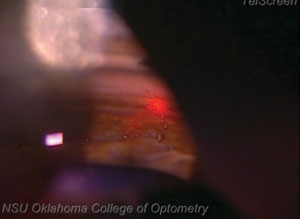

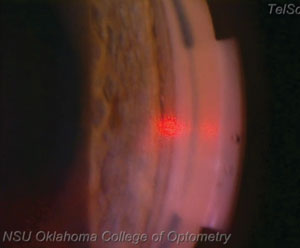

| The cavitation bubbles or “champagne” bubbles that can be seen throughout the trabecular meshwork as the procedure is performed lets the physician know that the laser is properly interacting with the tissue. |

Other surgical procedures, such as valves or stents, should be considered in preference to SLT when dealing with particularly advanced glaucoma, as in the case of severe, central VF defects, advanced cup-to-disc ratio greater than 0.8 in the vertical meridian or severe thinning on the OCT.

Side effects of the SLT procedure include transient IOP elevation after the procedure, inflammation, peripheral anterior synechiae, floaters, transient blurred vision, angle bleeding and possible corneal edema from endothelial cell loss.1 The two most common, albeit still rare, are transient IOP elevation and inflammation.1 Both of these can be easily controlled in most cases with pre- and postoperative topical medications.3

The SLT Procedure

Prior to the SLT, perform a comprehensive exam, including a best-corrected visual acuity, entrance skills testing, IOP evaluation and a slit lamp examination. A fundus, macula and optic nerve head evaluation should also be performed prior to SLT. Since patients are usually not dilated on the day of the SLT, a dilated fundus examination often takes place on a prior visit.

| |

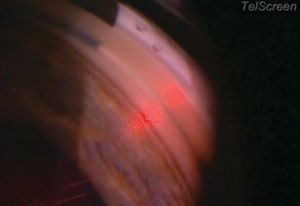

| The SLT procedure requires approximately 25 shots per quadrant, which is about 50 shots per 180 degrees, or, in this case, if you’re going all the way around, 100 shots for 360 degrees. |

Take a careful health history, including allergies, current medications, pulse and blood pressure.

It is critical to review the patient’s specific glaucoma diagnosis, current glaucoma treatments, as well as any history of past laser or surgical treatments.

Review with the patient a consent form detailing indications, contraindications, risks and benefits and alternative treatments and have the patient sign the form.

After you’ve completed the examination and obtained the proper consent, the steps of an SLT treatment are as follows:

1. Perform Gonioscopy. This should be done as part of the comprehensive workup before every SLT procedure. It is a critical step to determine how widely open the angle is, which determines how much room you will have to work in the angle during the procedure. It also will let you know how much pigment the patient has in the TM, which directly affects the energy level setting. A clinician who is particularly skilled in gonioscopy will have a tremendous advantage when performing the actual SLT procedure.

2. Instill preoperative medications. One drop of brimonidine or Iopidine is instilled 10 to 20 minutes prior to the procedure. Occasionally, pilocarpine is instilled preoperatively to give a more open view of the angle and TM; however, this is not usually needed. Proparacaine is instilled in both eyes to eliminate the blink reflex during the procedure.

| |

| At this point in the procedure, the laser is approximately at the 3 o’clock position, or 180 degrees from the starting point. Notice the champagne bubbles forming in the area where the laser has interacted with the tissue. |

3. Select the appropriate laser settings. Typical starting energy for an SLT is 0.8mJ to 1.0mJ per shot. The more pigment that is present in the angle, the more effective the laser will potentially be, since the SLT selectively targets pigment. With this in mind, turn the energy down to 0.5mJ to 0.7mJ/shot in heavily pigmented angles, as the laser will still be effective at this energy level while, at the same time, minimizing potential complications. In cases with little pigment in the angle, turn the energy up to 1.1mJ to 1.3 mJ/shot. Laser burn size for the SLT is 400µm, and laser burn duration is three nanoseconds (10-9 seconds). Both of these settings are fixed with the SLT laser and cannot be adjusted.

4. Insert the SLT lens. Performing an SLT requires insertion of an SLT laser lens on the eye. Starting placement for the mirror can occur anywhere. My preference is putting the mirror at the 9 o’clock position. This will allow a clockwise rotation of the mirror to cover the first 180 degrees (from 9 o’clock to 3 o’clock) in the superior quadrant view, which in actuality is the anatomic inferior quadrant. It is nearly always preferable to do the inferior 180 degrees first, since that is usually the most open angle with the heaviest amount of pigment. In a practical sense, it does not matter where you start, as long as you remember where you started so you know where to finish the procedure.

| |

| Notice how this laser sticks to the trabecular meshwork exclusively. When performing the SLT procedure, it is cruical to fire the laser only within the trabecular meshwork. Hitting too far anterior, into Schwalbe’s line, will likely result in decreased effectiveness, while hitting too far posterior will result in patient discomfort. |

5. Fire the laser. Starting at 9 o’clock, or your chosen starting location, place the single aiming helium-neon (he-ne) laser beam on the TM, covering it entirely. Fire laser spots one right next to the prior one, so that they are not overlapping while, at the same time, not spaced apart. Each shot should fall directly next to the previous shot. During the laser shots, minimal to no change in the tissue is seen other than the typical champagne bubbles. No charring, blanching, pits or craters are seen where previous laser spots have been placed, which again, makes it critical to remember where you started the procedure to avoid double treating areas of the TM. The typical number of laser pulses during the procedure is approximately 45 to 60 per 180 degrees for a half treatment, and 90 to 120 pulses per 360 degrees for a full treatment. Anatomically speaking, if the laser burns are placed too far anterior, nearing Schwalbe’s line or even anterior to that, the procedure is less likely to be effective, since the TM is no longer being treated. If the laser burns are placed too far posterior, in the area of the scleral spur or ciliary body, the patient is much more likely to feel discomfort during the procedure.

6. Determine whether you are performing 180 degrees or 360 degrees. Due to the findings of the SLT/MED study, among others, our standard is to perform a 360 degree SLT in one eye on the first visit, unless the patient has pigment dispersion syndrome/glaucoma with heavy pigment in the TM, in which case we will only perform 180 degrees. The second eye can be performed at a follow-up visit in the coming weeks.

7. Instill postoperative medications. Remove the SLT lens from the eye and instill postoperative medications. Brimonidine or Iopidine should be instilled again immediately after the procedure to reduce the risk of a transient IOP spike.

8. Check IOP. Check the IOP 30 to 60 minutes after the procedure to ensure it has not elevated significantly. IOP is typically lower 30 to 60 minutes after the procedure, due to the brimonidine that was instilled before and after. If the IOP is elevated by more than five points from the start of the exam, consider bringing the patient back the following day for an IOP check.

| |

| This image shows the laser returning to the 9 o’clock position, indicating the completion of the procedure. This patient had a significant enough reduction in IOP that he was able to discontinue one of his medications as a result of SLT. |

9. Prescribe NSAIDs. Dispense or prescribe a topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agent for residual pain and inflammation after the procedure. Patients can expect the eye to be mildly red and sore for two to three days after the procedure, and often find that a few drops of topical NSAID in the days after the procedure help to alleviate the redness and soreness. Protocols vary depending on the individual patient and doctor preference, but many doctors find it preferable to have the patient use a topical NSAID PRN for two to three days following the procedure.

10. Schedule a follow up. Perform a follow-up visit one to two weeks and six to eight weeks after the initial SLT laser. It typically takes six to eight weeks to see the full effect of the treatment. So, if you are only performing a half treatment or 180 degrees, wait six to eight weeks after the initial procedure to determine if the other 180 degrees needs to be done.

Retreatment

It is widely known that the effects of laser trabeculoplasty, both ALT and SLT, tend to wane with time. Evidence suggests that treatment effectiveness tends to last two to five years for most patients.8

SLT has been shown to be more repeatable than ALT in recent studies.8 Repeated treatments may not work quite as well, or last quite as long, but they are still largely

successful in many patients. SLT can also be performed on top of prior ALT.8

SLT has been around for longer than a decade now. Enough clinical and scientific evidence has been obtained to move this protocol to closer to the top of our treatment armamentarium.1-7

This quick and safe laser procedure frequently has an effect that lasts years and will often leave your patient’s mind at ease knowing they don’t have to worry about when and if they can get their next drop instilled.

Dr. Lighthizer is assistant dean for clinical care services, director of continuing education, and chief of the specialty care clinic and the electrodiagnostics clinic at NSU Oklahoma College of Optometry.

1. Katz L, Steinmann W, Kabir A, et al. Selective laser trabeculoplasty versus medical therapy as initial treatment of glaucoma: a prospective, randomized trial (SLT/MED Study). J Glaucoma. 2012;21:460–8.2. Waisbourd M, Katz L. Selective laser trabeculoplasty as a first-line therapy: a review. Can J Ophthalmol. 2014;49(6):519-22.

3. Samples J, Singh K, Lin S, et al. Laser trabeculoplasty for open-angle glaucoma: a report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology 2011;118:2296–302.

4. Katz L, Schubert H. Argon laser trabeculoplasty vs. selective laser trabeculoplasty. Survey of Ophthalmology 2008;53(6).

5. Tanna A, Rademaker A, Stewart W, Feldman W. Meta-analysis of the efficacy and safety of a2-adrenergic agonists, b-adrenergic antagonists, and topical carbonic anhydrase inhibitors with prostaglandin analogs. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128(7)825-33.

6. Ayala M, Chen E. Long-term outcomes of selective laser trabeculoplasty (SLT) treatment. The Open Ophthalmology Journal. 2011;5:32-34.

7. McIlraith I, Strasfeld M, Colev G, Hutnik C. Selective laser trabeculoplasty as initial and adjunctive treatment for open-angle glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 2006;15:124–30.

8. Hong B, Winer J, Martone J, et al. Repeat selective laser trabeculoplasty. J Glaucoma. 2009;18(3):180–3.