|

Diabetic macular edema (DME) contributes significantly to vision loss in diabetes patients and is the most common cause of vision loss among young adults. Previously, these patients were subjected to focal or grid laser photocoagulation. Although this method was effective in reducing vision loss by 50%, it was ineffective in restoring lost vision. All patients who participated in the original Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) had visual acuity of 204/0 or worse.1

Fortunately, management of DME has improved over the last decade and has increased the potential of visual restoration with the approval of anti-VEGF compounds Lucentis (ranibizumab, Genentech) and Eylea (aflibercept, Regeneron), and the off-label use of Avastin (bevacizumab, Genentech). Given the role inflammation plays in the development of DME, steroids have also become an effective option in DME management. Ozurdex (dexamethasone, Allergan) is a time-release intravitreal implant that emits a low dose of dexamethasone over 90 to 120 days. Another implant, Iluvien (fluocinolone acetonide, Alimera Sciences), the most recent therapy approved to treat DME, has an efficacy of up to 36 months. Focal or grid macular laser is also still used for clinically significant macular edema.

The ways we detect and define DME have evolved, too. Classification of DME is now based more on optical coherence tomography (OCT) images than funduscopy. The world of ophthalmology and retina in general is moving away from the classification of clinically significant macular edema (CSME), which primarily relied on funduscopic findings, and more towards spectral-domain OCT (SD-OCT) findings and retinal thickness. Now, DME is broken down into “center involved” (CI-DME) and “non-center involved” (NCI-DME) cases based on SD-OCT subfields.

These advances have given retina specialists and comanaging optometrists more options for management of DME—but also more room for doubt and debate regarding whether, when and how to intervene.

|

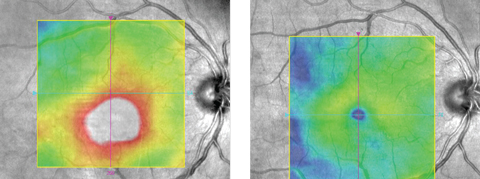

| Figs. 1 and 2. This patient’s center-involved DME (left) responded well to anti-VEGF (right). |

A Tale of Two Patients

By Dr. Haynie

Case 1. A 51-year-old white female presented for an evaluation with a six-month history of blurred vision in the right eye. Her medical history includes hypertension and 12 years of Type 2 diabetes. Her medication history included metformin and glyburide for diabetes, and lisinopril for hypertension. Her best-corrected visual acuity measured 20/40 in the right eye and 20/20 in the left eye. The anterior segment exam was unremarkable, and she was phakic. Dilated examination revealed moderate nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR) with multiple dot-blot hemorrhages and central macular thickening). SD-OCT confirmed CI-DME (Figure 1).

She was treated with serial anti-VEGF injections, variously using bevacizumab and aflibercept. She responded well, achieving resolution of the edema and a recovery in vision to 20/20 with stable OCT images (Figure 2).

This case may seem straightforward, and the retinal referral was considered both necessary and unremarkable. Now let’s look at another case of DME and discuss how the referral and management may differ.

|

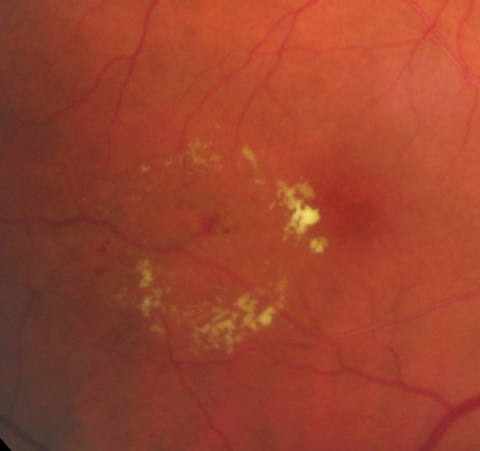

| Fig. 3. Circinate lipid ring in case 2. |

Case 2. This 68-year-old Native American female was referred for an evaluation of diabetic retinopathy and macular edema. She reported that her vision had been stable with no recent symptoms. Her medical history included Type 2 diabetes of 12 years’ duration, hypertension and cardiac arrhythmia. Medications included glargine and metformin for diabetes, and amlodipine, metoprolol and clopidogrel for hypertension. Entering best-corrected visual acuity measured 20/25 in each eye. Anterior segment evaluation revealed grade 2 nuclear cataracts in each eye. Dilated fundus examination revealed mild NPDR in each eye with a circinate ring of lipid in the temporal macula of the right eye (Figure 3). SD-OCT imaging revealed NCI-DME with a normal foveal contour and thickness.

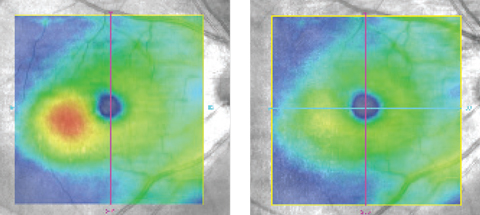

After a discussion of the available treatment options, including serial anti-VEGF intravitreal injections, she elected to observe rather than treat. After three months, the NCI-DME resolved and her vision was maintained at 20/25 in the right eye (Figures 4 and 5).

|

| Figs. 4 and 5. The macular edema (left) resolved without therapy at three months (right). |

How Our Practice Compares

By Dr. Shechtman

Given that I practice in a retina clinic in South Florida, we are inundated with cases similar to the ones described above. The question of whether to treat or observe has become increasingly controversial. DME is dynamic and, as Dr. Haynie points out in case 2, may have the potential for resolution without intervention. Hence, it is critical to educate the patient about the importance of tight glycemic control.

Yet, many cases will progress and, if untreated, result in decreased visual acuity. Thus, all five surgeons at my practice would agree with the management of case 1. In the presence of decreased visual acuity (i.e., <20/25) and CI-DME, anti-VEGF therapy is initiated at our practice. Patients are often treated for about three months. If further assistance is necessary, we’ll consider a steroid implant such as Ozurdex or Iluvien. Keep in mind that prior to the use of Iluvien, it is recommended to have the patient on a steroid challenge to minimize the potential of complications such as glaucoma.

Case 2 may not be as straightforward. In cases of NCI-DME with good visual acuity, we may observe but still evaluate for the presence of CSME as defined by the ETDRS (retinal thickening and hard, yellow exudates within 500µm of the foveal center and at least one disc area of thickening within one disc diameter of the foveal center). These cases often show increased focal macular edema on the ETDRS retinal thickness OCT grid, but the increased thickness is not confined to the central area. In our practice, many cases defined as CSME may still benefit from focal laser. Yet, the management of each case is assessed on an individual basis.

Studies such as the Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network’s Protocol V may in fact help us to better assess the efficacy of anti-VEGF therapy in cases where the visual acuity is 20/25 or better.2 This study compares three approaches to management in patients with center-involved DME but good visual acuity: (1) prompt use of laser plus deferred anti-VEGF, (2) observation plus deferred anti-VEGF and (3) prompt use of anti-VEGF therapy.

Researchers hope the results will reveal how long anti-VEGF therapy can be deferred and the impact of observation or laser treatment in such cases. There is still debate as to the prompt use of anti-VEGF: does the benefit justify accepting the known risks, and what is the optimal number of injections needed to maintain vision? Hopefully, Protocol V’s results will shed some light.

1. Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study Research Group. Early photocoagulation for diabetic retinopathy. ETDRS report number 9. Ophthalmology. 1991 May;98(5 Suppl):766-85. |