The visual system develops throughout different milestone periods in early childhood; however, not everyone is able to acquire or master complex visual skills.1-3 Research shows that 25% of grade school children have vision problems that are often undiagnosed.2,3 Children who struggle with vision disorders may encounter challenges in the classroom, recreational play or sporting activities.

Because of the high prevalence and incidence of vision disorders, primary care optometrists and other healthcare professionals should address this area of concern appropriately. Early intervention is critical because vision problems can develop in adulthood if they are not addressed sooner.1-3 This article briefly reviews some common pediatric vision disorders and discusses possible diagnostic, treatment and management strategies.

|

| Use the NSUCO oculomotor test to assess pursuit eye movements. Click image to enlarge. |

Oculomotor Dysfunction

This common visual disorder is characterized by an anomaly in fixation, saccades or pursuit eye movements.3,4 Symptoms might include a reader losing their place on a page, skipping words or lines of content, re-reading words or reading one word slowly at a time.3,5-7 These disruptions interfere with fluency development and academic motivation.3,6-8 If these deficits are not properly assessed and treated, they may interfere with educational learning, depth perception and sports participation.2,7-9 Over time, patients may develop compensatory habits, such as moving their head or using their finger as a guide during reading, to avoid visual symptoms.1,2,7,8

Different methods exist to assess oculomotor function.3,4,10 The Northeastern State University College of Optometry (NSUCO) oculomotor test is a quick and effective test to check gross oculomotor function.10 It is based on four parameters: ability (how long the child stays with the task), accuracy (saccadic intrusions, refixations for pursuits and by over- or undershoots for saccades), head movement and body movement (ability to control motor overflow).10

To test pursuits, instruct the patient to follow a near rotating target without taking their eyes off of it.10 With saccades, use two different targets and have the patient alternate viewing between each one only when instructed to do so.10 For pediatric patients, bright, and colorful targets help to maintain good visual attention.3,4

Other diagnostic oculomotor tests include the Developmental Eye Movement (DEM) and the King-Devick, which subjectively evaluate linear visuomotor skills, rapid automated naming skills and visual processing speed.6,9,11-13 Specifically, the DEM differentiates automaticity and oculomotor deficits, while the King-Devick test cannot differentiate the two. Objectively, the visagraph (Bernell) and readalyzer (Bernell) use video-oculography to analyze micro-ocular movements and estimate an approximate reading grade level.14 With each test, carefully observe for compensatory head movements or finger guides without giving prior instructions on head and hand positioning.4,11,14

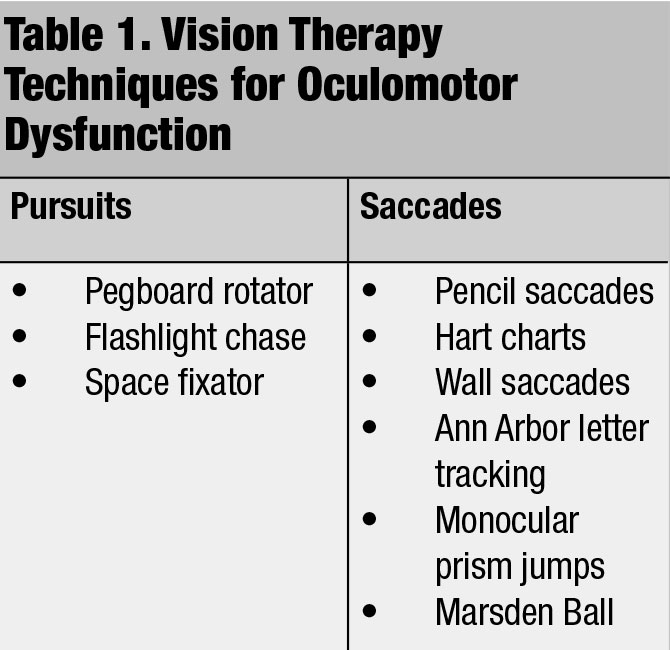

Vision therapy is the treatment of choice for oculomotor dysfunction (Table 1).3,4,7 Use sequential techniques that train both gross and fine oculomotor movements properly.3,4,7 To make these tasks more challenging, consider loading each technique with items such as a metronome or balance board.3,4,7

|

Amblyopia

There are three types of amblyopia: visual deprivation, refractive error and strabismus.15-17 With visual deprivation amblyopia, there is a structural obstruction of the eye that prevents light to enter, resulting in a failed visual response being sent to the brain.16 Several conditions cause visual deprivation amblyopia, such as congenital cataracts, eyelid ptosis and corneal opacities.15-17 Treat the incriminating factor first to eliminate the obstruction prior to addressing this type of amblyopia with therapy.15-17

Uncorrected refractive error causing amblyopia occurs because the visual information sent to the brain is blurred due to larger refractive errors.15-17 The higher the refractive error, the greater the risk of amblyopia.15-17

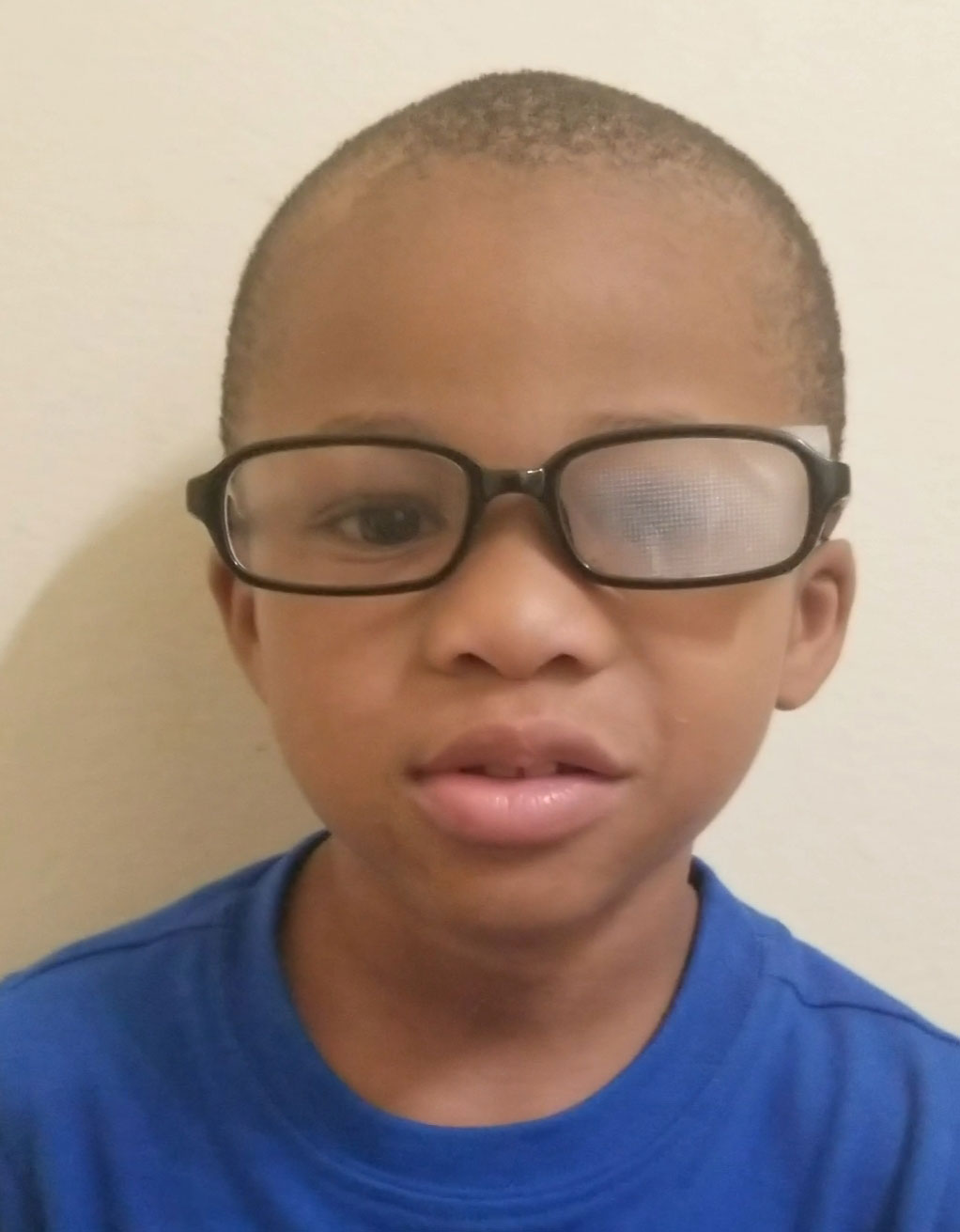

While examining the patient, look for clues that may suggest amblyopia. During visual acuity testing, they may slowly read the letters on the chart, try to peek around the photoper or remove the occluder, allowing the sound eye to see. Optical correction can improve visual acuity in the amblyopic eye.15-17 Light or flexible frames are a good recommendation for children. Head straps or temple cables can also optimize an appropriate fit. Impact resistant polycarbonate lenses should be recommended to all pediatric patients.

Patching is another effective treatment approach in amblyopia, as it forces the brain to receive and process visual information from the amblyopic eye.18-21 Studies show that patching for two hours a day is as effective as longer patching times.15,17 Adhesive patches can be used to ensure patients are receiving effective treatment. Previously, studies recommended near activities during patching hours; however, more recent research shows that patients performing distance activities while patching are as effective in visual recovery.15,17

|

An alternative to patching is pharmacological penalization with cycloplegic agents, which forces the patient to use visual input from their amblyopic eye for near tasks.15-17 Atropine 1% is commonly used in practice and has yielded positive results.21,22 Clinical studies reveal that pharmacological penalization results are similar to patching alone.16,17,21,22 One advantage to this type of therapy is that it increases compliance due to easy installation. It is also good for milder degrees of amblyopia.16,17 Advise patients on possible symptoms of decreased visual acuities in the non-amblyopic eye and increased photosensitivity secondary to mydriasis.16,17

Optical penalization can also be used to blur the spectacle prescription in the good eye while maximizing the prescription in the amblyopic eye.16,17 Bangerter filters are also options where a translucent filter is placed over the lens of the nonamblyopic eye to cause blur.15-17 Cosmetically, they are less noticeable than an eye patch, making them a good option for patients who are conscience of the appearance. For these therapies to work, the patient has to wear their glasses.15-17

Dichoptic treatment is also available, in which patients receive more visual stimulation through higher contrast and brighter images in the amblyopic eye.16,23,24

Regular follow-ups are important to assess whether the amblyopic eye is strengthening. Improvement with therapies can take weeks to reveal any progress, and compliance can be difficult. While most children show improvements with these therapeutic approaches, not all pediatric patients respond.16,23,24 In my practice, we treat amblyopia first before undergoing strabismic strategy if heterotropic or hypotropic deviations are present.16,23,24

|

Strabismus

According to the American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, this condition affects a little more than 3% of children in the US population.25 Some causes of strabismus include large uncorrected refractive error, paretic extraocular muscles, genetic developmental disorders and trauma.25,26

Depending on the degree of misalignment, patients may present with symptoms of diplopia, blurred vision, headaches, eye fatigue, difficulties with reading and eye strain.1,6 However, some strabismic patients are asymptomatic due to visual suppression of the weaker eye and preferential use of the dominant, or clearer, eye.25 Traditionally, strabismus amblyopia patients have this type of visual profile.25,26

Many clinical techniques can assess strabismus.25,26 Use a transilluminator or near fixating target and observe eye movements in all nine cardinal directions to ensure the proper function of all extraocular muscles and that both eyes are working with each other simultaneously.25,26 While some large angle deviations are obvious, other subtle misalignments may be difficult to pick up.18,25,26

Use cover tests to identify phorias and tropias.26 A unilateral cover test (cover-uncover test) will reveal the presence of a tropia if the clinician looks at the eye not being covered.6 During the unilateral cover test, the strabismic eye will attempt to correct itself either by moving inward (exotropia) or outward (esotropia).26 The alternating cover test (cross-cover test) is used to break fusion to detect a phoria when the clinician observes the eye after it is uncovered.26 Use prism bars or loose prisms to measure the magnitude of the deviation during the test. Titrate the necessary amount of prism until no movement is seen as the occluder is alternately switched from eye to eye.26

The Hirschberg test is another useful clinical tool that detects misalignment using the direct ophthalmoscope or transilluminator.26 During this test, look at the corneal reflex and compare its position to the underlying pupil. Normally, the corneal reflex should lie exactly over the pupil. For every millimeter that the corneal reflex is off-center, it is equivalent to 22 prism diopters of deviation.26

The first visual corrective option for any strabismic patient should be spectacles to improve visual acuity, stereopsis and ocular alignment.26 Plus lenses in accommodative esotropia cases may aid with focusing and visual discomfort symptoms.25-27 Other treatment options include prisms, vision therapy and patching.18,26

If spectacle or prism correction do not improve the misalignment, surgical intervention is available to correct the deviation.26 The Infantile Esotropia Observation Study showed that infants who had surgery at six months experienced better stereoscopic outcomes at four years of age compared with infants who underwent surgery after six months.27,28

Early intervention is required in constant deviations that do not improve with spectacles or other noninvasive treatment options.26,27 Only then should you consider surgery to correct the deviation and improve stereopsis ability.25,26

|

| Optical penalization can be used to treat amblyopia. Click image to enlarge. |

Accommodative & Vergence Disorders

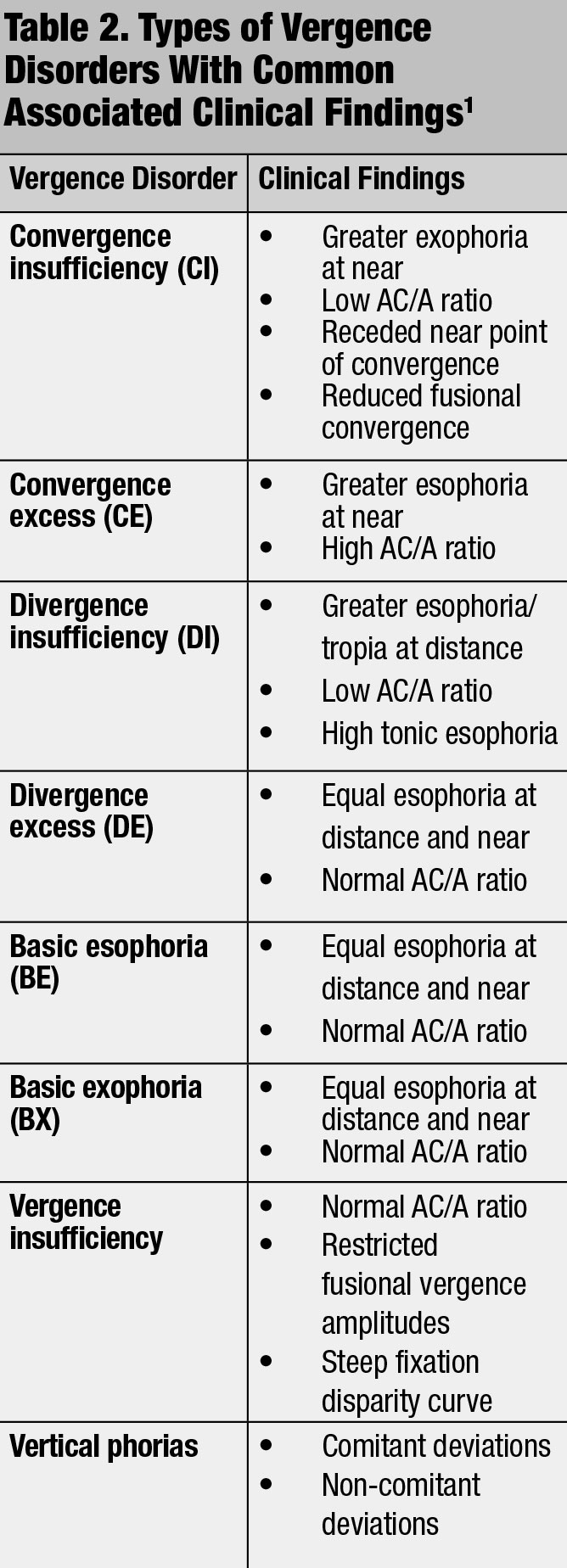

School-aged patients, especially third and fourth graders who have reading difficulties, diagnosed learning disabilities or poor academic performance should have a comprehensive vision exam to evaluate for underlying accommodative and vergence problems. These conditions can have a significant impact on the increased near viewing demand and workload.1-3,7

Ratios below and above the normal convergence induced by accommodation per unit of accommodation (AC/A) ratio, 4:1, have been implicated in binocular vision problems (Table 2).1,3,7 Incorporate accommodative testing into the phoropter routine by adding plus or minus lenses until the patient first notices unresolved blur.3 Monocular estimate method (MEM) retinoscopy is a binocular test performed behind the phoropter using a reading card that can attach to the face of the retinoscope. Similar to standard retinoscopy, neutralize the “with” (lag of accommodation) or “against” (lead of accommodation) motion with the appropriate lenses until no movement is observed.1,3,7 Other dynamic retinoscopy (e.g., Nott) tests can check accommodation abilities.1,3,7

Convergence insufficiency is the most common vergence disorder affecting the ability to maintain proper binocular eye alignment on near targets, resulting in visual discomfort at near.3,7 Assess vergence skills in office with techniques such as near point convergence and fusional divergence and convergence tests to assess the efficiency abilities of this system.

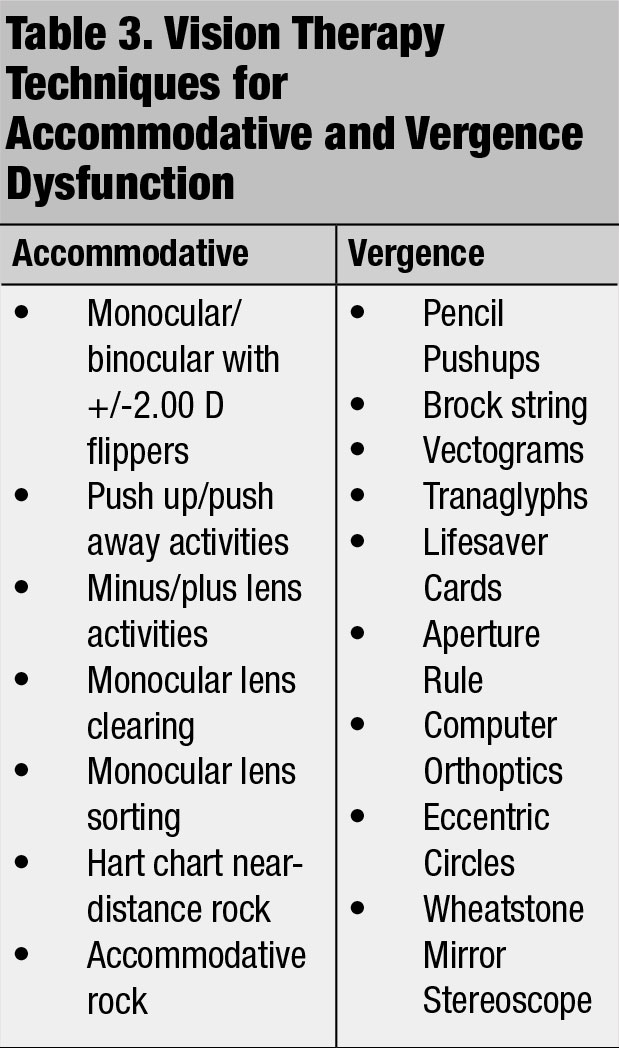

Recommend corrective lenses, vision therapy (Table 3) or orthoptics as treatment options to improve deficient accommodative and vergence skills.1,3,4 Specifically, add a plus lens for accommodative dysfunction to improve the patient’s focusing skills.1,3,4 Vision therapy techniques can be loaded with increasing plus/minus lenses or prism amounts.4 Carefully monitor for suppression during vergence therapy techniques.1,3,4

If children present with any of these vision disorders, they may experience challenges when reading, writing and computer use, ultimately lowering their educational potential.

As primary eye care providers, we have a duty to advocate for our younger patients. We must recommend comprehensive eye exams with careful assessments for the presence of vision disorders. If present, we must offer the appropriate treatments and advise regular follow-ups.

Dr. McGhee practices at Chiasson Eye Center and Bond Wroten Eye Clinic in Louisiana.

1. American Optometric Association Consensus Panel on Care of the Patient with Accommodative and Vergence Dysfunction. Accommodative and Vergence Dysfunction. St. Louis, MO: American Optometric Association; revised 2017. 2. Schuhmacher H. Vision and Learning: A Guide for Parents and Professionals. Hamburg:Tredition; 2017. 3. Scheiman M, Wick, B. Clinical Management of Binocular Vision: Heterophoric, Accommodative, and Eye Movement Disorders. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2013. 4. Damari DA. Vision Therapy for Non-Strabismic Binocular Vision Disorders A Evidence-Based Approach. OptoWest; 2013. www.academia.edu/36635747/Vision_Therapy_for_Non-Strabismic_Binocular_Vision_Disorders_A_Evidence-Based_Approach. Accessed June 3, 2019. 5. Kulp M, Schmidt P. The relation of clinical saccadic eye movement testing to reading in kindergartners and first grades. Optom Vis Sci. 1997;74(1):37-42. 6. Powers M, Grisham D, Riles, P. Saccadic tracking skills of poor readers in high school. Optometry. 2008;79(5):228-34. 7. Rouse M. Optometric assessment: visual efficiency problems. In: Scheiman M, Rouse M, eds. Optometric Management of Learning-related Vision Problems. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Mosby Elsevier; 2005:335-67. 8. Ayton LN, Abel LA, Fricke TR, McBrien NA. Developmental eye movement test: what is it really measuring? Optom Vis Sci. 2009;86(6):722-30. 9. Palomo-Álvarez C, Puell, MC. Relationship between oculomotor scanning determined by the DEM test and a contextual reading test in schoolchildren with reading difficulties. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2009;247(9):1243-9. 10. Maples WC. NSUCO Oculomotor Test. Santa Ana,CA: Optometric Extension Program Foundation; 1995. 11. Garzia RP, Richman JE, Nicholson SB, Gaines CS. A new visual verbal saccade test; the developmental eye movement test (DEM). J Am Optom Assoc. 1990;61(2):124-35. 12. Luna B, Velanova K, Geier CF. Development of eye-movement control. Brain Cogn. 2008;68(3):293–308. 13. Moiroud L, Gerard CL, Peyre H, Bucci MP. Developmental Eye Movement test and dyslexic children: A pilot study with eye movement recordings. PLOS One. 2018;12(9):e0200907. 14. Webber A, Wood J, Gole G, Brown B. DEM test, visagraph eye movement recordings, and reading ability in children. Optom Vis Sci. 2011;88(2):295-302. 15. Rouse M, Cooper J, Cotter S, et al. Care of the patient with amblyopia: the American Optometric Association Optometric Clinical Practice Guidelines. 2004. www.aoa.org/documents/optometrists/CPG-4.pdf. Accessed June 3, 2019. 16. Arnold R. Amblyopia risk factor prevalence. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2013;50(4):213-7. 17. Jenewein E. Amblyopia: when to treat, when to refer? Rev Optom. 2015;152(12):48-54. 18. Mohney BG, Cotter SA, Chandler DL, et al. A randomized trial comparing part-time patching with observation for intermittent exotropia in children 12 to 35 months of age. Ophthalmology. 2015;122(8):1718-25. 19. Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group. The clinical profile of moderate amblyopia in children younger than seven years. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120(3):281-7. 20. Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group. The course of moderate amblyopia treated with patching in children: experience of the amblyopia treatment study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;136(4):620-9. 21. Scheiman MM, Hertle RW, Kraker RT, et al. Patching vs. atropine to treat amblyopia in children aged seven to 12 years: a randomized trial. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126(12):1634-42. 22. Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group. The course of moderate amblyopia treated with atropine in children: experience of the amblyopia treatment study. Am J Opthhalmol. 2003;136(4):630-9. 23. Wallace D, Chandler DL, Beck RW, et al. Treatment of bilateral refractive amblyopia in children three to <10 years of age. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;144(4):487-96. 24. Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group. Effect of age on response to amblyopia treatment in children. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129(11):1451-7. 25. American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. Strabismus. February 26, 2019. aapos.org/glossary/strabismus. Accessed June 3, 2019. 26. Caloroso EE, Rouse MW, Cotter SA. Clinical Management of Strabismus. Boston: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1993. 27. Birch E, Stager D, Wright K, Beck R. The natural history of infantile esotropia during the first six months of life: Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group. J AAPOS. 1998;2(6):325-9. 28. Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group. Spontaneous resolution of early-onset esotropia: experience of the Congenital Esotropia Observational Study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;133(1):109-18. |