|

Q:

I have a patient with a suspicious white spot in the cornea, with a history of contact lens overwear and poor compliance. How do I handle this case?

A:

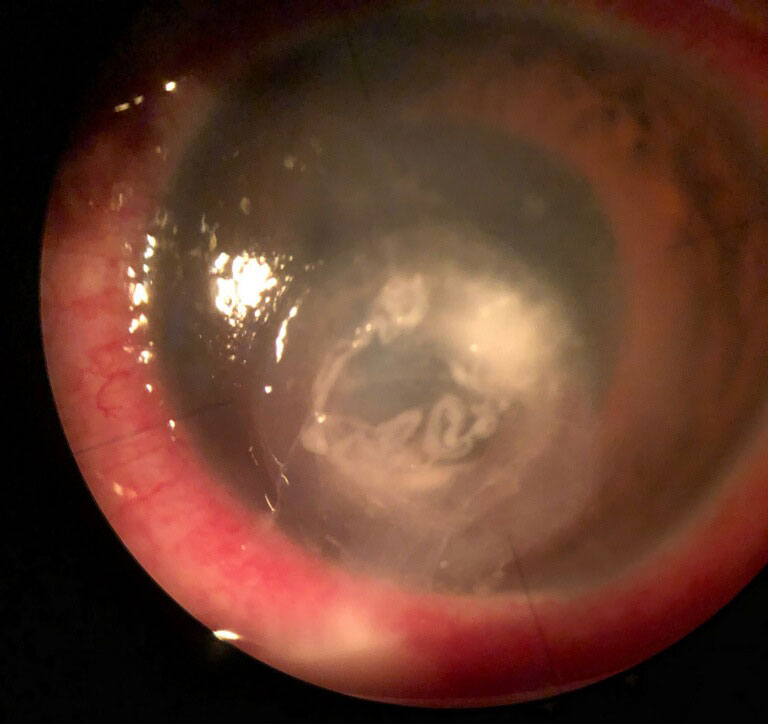

“Deciding whether a patient has a corneal ulcer (bacterial infection) vs. a corneal infiltrate (sterile inflammation) can be one of the more challenging decisions we make,” says Chris Cakanac, OD, of Your Family Eye Doctors in Murrysville, PA. While the two appear as whitish corneal lesions on a red eye, a closer look can offer clues, he notes. An ulcer is defined as a bacterial infection, often with an overlying epithelial defect and associated stromal infiltration. Ulcers tend to irritate the eye much more than an infiltrate. Expect severe diffuse conjunctival injection, often with a significant anterior chamber reaction or even hypopyon.

Infiltrates tend to have less injection and minimal anterior chamber reaction. “If there is no fluorescein staining (or just a trace), it is usually an indication you are dealing with a corneal infiltrate,” Dr. Cakanac says.

Other differentiators include more pain in the infectious ulcer patient, as opposed to only light sensitivity and irritation in the infiltrate patient. A few other general characteristics, although there are always exceptions, include:

(1) Ulcers are single lesions more often than infiltrates, which can be multiple.

(2) Ulcers tend to be larger (2mm or more) while infiltrates are smaller.

(3) Infiltrates tend to accumulate along the limbus; a response to hypoxia from contact lenses or Staph. exotoxins in a blepharitis patient. Also look for blood vessel ingrowth.

“So, poor contact lens compliance related to overwear and poor hygiene, along with chronic Staph. lid disease, are often the culprits behind both ulcers and infiltrates,” Dr. Cakanac adds.

|

| Determining the nature of a white corneal lesion requires a closer look. Click image to enlarge. |

Treatment Protocols

In days gone by, the standard of care for a corneal ulcer was to obtain a culture and sensitivity on every one, according to Dr. Cakanac. As our therapeutic agents have dramatically improved, cultures and sensitivities are now reserved for cases threatening the visual axis or not responding to treatment.

“If you’re a practitioner who likes rules, consider the ‘1-2-3 rule’—culture any ulcer within 1mm of the visual axis, any ulcer with two or more infiltrates or any ulcer with a larger than 3mm epithelial defect,” Dr. Cakanac says. And you may want to culture the contact lens case as well.

Successfully treating an ulcer (infection) requires an antibiotic. By contrast, an infiltrate (sterile inflammation) requires a steroid. When in doubt, it is always safer to begin with a topical antibiotic. The steroid can always be added later. For early lesions, a commercially available fluoroquinolone is usually adequate. For more serious ulcers, the standard is still the combination of either cephazolin fortified to 50mg/ml or vancomycin fortified to 25mg/ml to cover gram-positive organisms, as well as tobramycin fortified to 14mg/ml to cover gram-negative strains.

“Know where your nearest compounding pharmacy is and what their hours are, so that in an emergency you can get drops made up,” Dr. Cakanac advises.

Once considered a contraindication, adding a topical steroid to antibiotic therapy for an ulcer can decrease overall ocular inflammation, pain and possibly scarring, many experts now believe. The Steroids for Corneal Ulcers Trial showed that while adding a steroid did not statistically improve visual outcomes, there was no increased risk of corneal perforation.1

Corneal infiltrates usually respond to most topical steroids in standard doses. “If the diagnosis is in question, use a concurrent topical antibiotic,” Dr. Cakanac notes.

| 1. Jacob MK. Idiopathic orbital inflammatory disease. Oman J Ophthalm. 2012;5(2):124-5. |