11th Annual Pharmaceuticals ReportFollow the links below to read other articles from annual update on pharmaceuticals: Know Your Systemic Meds: The Top 10 to Track Sizing Up Anti-inflammatories in Dry Eye Disease Protocols and Pitfalls of Topical Steroid Use |

Due to their complexity and temperament, ocular infections can be a pain to treat. Finding the right antibiotic requires a thorough understanding of the most likely causative organisms, resistance patterns, patient-specific data and pharmacologic information that may impact the patient’s response to the drug. And we have to do it all while the clock is ticking—the earlier treatment begins, the better the prognosis. However, sometimes, less is more. Exercising discretion in situations where the infection is most likely to be caused by a virus, such as in non-purulent infectious conjunctivitis, has been proven to decrease the spread of resistant organisms.1,2

Into this thicket walks the optometrist, who must navigate carefully and make many decisions to move forward safely.

|

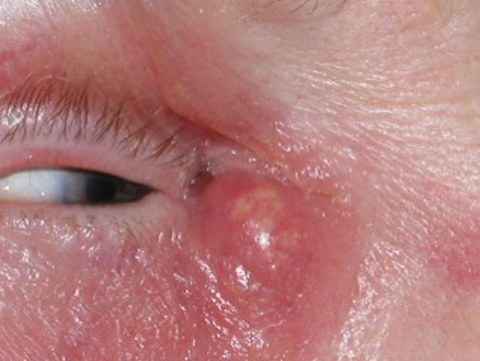

| These images show a patient with dacryocystitis and preseptal cellulitis before being treated with antibiotics. |

|

Chiefs of Staph.

The first key question is whether to use an oral or a topical agent. Oral antibiotics are accepted as the standard of care when treating infections such as hordeolum, preseptal cellulitis and dacryocystitis.3,4 Compared with topical antibiotics, orals produce significant levels in the bloodstream, which provide superior penetration of the lacrimal apparatus and surrounding tissues. For this reason, these infections are more effectively treated with an oral agent.3

Most corneal and conjunctival infections are best managed with a topical fluoroquinolone, perhaps with an oral agent added for more coverage if circumstances warrant.

Common organisms associated with hordeolum, dacryocystitis and preseptal cellulitis include the gram-positive organisms Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis and Streptococcus pneumonia (Table 1). But they also include gram-negative organisms such as Haemophilus influenza and occasionally Pseudomonas aeruginosa.5-7

When choosing an oral antibiotic to treat these relatively common ocular infections, inquire about the presence of allergy, pregnancy, breastfeeding, comorbidities, drug interactions, prior antibiotic use and ability to pay out of pocket for the more costly medications.

|

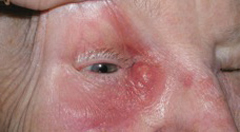

| These images show the same patient from page 52 a week after initiating antibiotic treatment. |

|

MRSA Matters

Since methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is a common colonizer on skin, clinical consideration should be given to determine whether a patient needs antibiotic coverage for this organism. This is typically determined by local prevalence and risk factors.5-7

While sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim (SMX-TMP), doxycycline and clindamycin may not be an OD’s typical “go to” drugs when treating hordeolum, preseptal cellulitis and dacryocystitis, they are important to consider, especially when managing community-acquired (as opposed to hospital-acquired) resistant Staph. aureus MRSA infections (Table 2).33

In the past, practitioners relied on intravenous vancomycin to treat MRSA infections, but today we are fortunate to have SMX-TMP, doxycycline and clindamycin in our MRSA arsenal. Doxycycline is generally considered a “last-line” in the trio of agents that cover MRSA, mainly because of tolerability issues. When a patient fails traditional therapy that covers Staph. aureus, or when a patient is colonized with MRSA, it’s a good time to consider a potential MRSA infection. Susceptibility to MRSA is also heightened in young patients, prisoners and athletes.29,30,33

Table 1. Likely Organisms Responsible for Lid/Adnexal Infections | |

| Hordeolum | Staphylococcus aureus |

| Preseptal Cellulitis | Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae |

| Dacryocystitis | Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa |

| The resolution of this patient’s dacryocystitis and preseptal cellulitis was achieved using antibiotics. |

Beta-Lactams

These antibiotics are widely used to treat upper respiratory tract infections and ocular infections (Table 3).

Amoxicillin and amox + clavulanate. These agents are considered amino-penicillins or extended spectrum penicillins because the amino side-chain extends its coverage to include more gram-negative organisms such as Haemophilus influenza and the Enterobacteriaceae family, such as Escherichia coli, when compared with penicillin VK.

Additionally, these agents have good coverage against sensitive Staph. aureus and even Streptococcus pneumoniae when given in high doses. Keep in mind that coagulase-negative Staph. species (e.g., Staph. epidermidis) show a decent amount of resistance to these agents and may not be a reasonable choice in a patient infected with this organism. Neither MRSA nor Pseudomonas aeruginosa is susceptible to these agents.9,10

Mechanistically, these agents inhibit bacterial cell wall synthesis by plugging into penicillin-binding proteins. This results in bacterial cell death. The addition of the beta-lactamase enzyme inhibitor clavulanate provides increased protection for amoxicillin against hydrolysis when it’s exposed to infections caused by organisms that produce beta-lactamase, including Haemophilus influenzae and Moraxella catarrhalis.

While traditional penicillin has impaired gastrointestinal absorption when given with food, amoxicillin is relatively stable. Additionally, amoxicillin plus clavulanate has improved gastrointestinal tolerability when given with food and is generally recommended that patients take it with a meal. While both amoxicillin and amoxicillin plus clavulanate are both fairly well-tolerated, the latter is more likely to cause nausea and vomiting. Drug interactions with these two agents are miniscule, and the regimen is generally considered safe to take while pregnant.9-11

Cephalexin. A first-generation cephalosporin, this has gram-positive coverage similar to amoxicillin, but is considered more stable against hydrolysis by beta-lactamase–producing organisms. MRSA and Pseudomonas aeruginosa are not susceptible to this agent. Side effects with cephalexin are well-tolerated and include miniscule drug interactions. In general, cephalexin has also been considered safe in pregnancy.9,10

Allergy ambiguities. Decades of clinical research have allowed us to fine-tune our understanding of penicillin allergies and the potential cross-reaction between a penicillin allergy and other beta-lactam antibiotics (Table 4). While some sources report cross-reactions between penicillins and cephalosporins occurring as often as 10% of the time, other research suggests that this is an exaggeration. Nevertheless, the mere “potential” of this cross-reaction has created a culture in which physicians tend to avoid beta-lactam agents and overuse the broader spectrum agents such as macrolides and fluoroquinolones.

When evaluating a patient who claims to possess a “penicillin allergy,” practitioners should investigate the specific nature of the allergic reaction to the drug. Researchers estimate that 90% of patients who claim to be allergic to a penicillin are not actually allergic.9,10,12-14

Typically, the cephalosporins, possessing similar side chains, increase the likelihood of a cross-reaction. For example, cephalexin is more likely to cross-react with a patient who has penicillin allergy compared with a drug lacking the side chain (e.g., cefuroxime axetil). If a patient is listed as having an allergy to a cephalosporin, it’s wise to consider that claim to be true. Also, a cross-reaction from a cephalosporin to a penicillin is rare.12-15

Table 2. Dosing Regimens for Community-Acquired MRSA29,30,33 | |

| Sulfamethoxazole+Trimethoprim DS | 800mg/160mg; take one tab BID x 10 days |

| Clindamycin | 300mg to 600mg TID x 10 days |

| Doxycycline | 100mg BID x 10 days |

|

| This patient presented with a visible dacryocystitis infection, which required antibiotic treatment. |

Meet the Macrolides

The macrolide class of agents includes erythromycin, clarithromycin and azithromycin. Erythromycin is incredibly well-known to cause nausea and vomiting and is typically taken three to four times per day. For obvious reasons, this agent is rarely used in eye care.

Clarithromycin, on the other hand, causes a moderate amount of nausea and vomiting and is dosed BID. As it shows no real benefit over azithromycin, it is used less.

The third agent in this class, azithromycin, proves fairly well-tolerated and is reported as having the fewest drug interactions. It has become the drug of choice for infections requiring a macrolide treatment. It is taken twice daily on the first day and then once for another four days. Due to the post-antibiotic effect, five days of therapy treat bacteria systemically for approximately 72 hours past the last dose.18

Table 3. Dosing Regimens for Beta-Lactam Agents | |

| Amoxicillin | 500mg BID-TID x 10 days 875mg BID x 10 days* |

| Amoxicillin+Clavulanate | 500mg/125mg BID-TID x 10 days 875mg/125mg TID x 10 days* |

| Cephalexin | 500mg BID x 10 days |

| * higher dose = increased S. pneumoniae coverage. | |

|

| This 28-year-old patient’s redness is due to hordeolum and cellulitis. |

When Side Effects Set In

Pharmacologically, once we move away from inhibitors of bacterial cell wall synthesis (beta-lactams), we begin to see more side effects from antibiotics because they have an effect on bacterial cells and mammalian cells that are rapidly dividing. Examples of these rapidly dividing cells include those found in the skin, gut and bone marrow.16,17

Mechanistically, the macrolides are protein synthesis inhibitors and bind to the 50S ribosomal subunits in susceptible organisms. Staph. aureus and Strep. pneumoniae are generally less sensitive to azithromycin as compared with the beta-lactam agents.

On the contrary, Haemophilus influenzae is generally more sensitive to azithromycin than to the beta-lactam agents. While azithromycin is generally well tolerated, with occasional mild gastrointestinal complaints, it may cause QT prolongation (a heart arrhythmia) in susceptible patients. It has miniscule drug interactions and is generally considered safe in pregnancy.16-18

Table 4. Penicillin Allergy Quick Facts12-14

|

Face the Fluoroquinolones

The fluoroquinolone group of systemic antibiotics includes levofloxacin, ciprofloxacin, moxifloxacin and gemifloxacin, colloquially knows as the “respiratory fluoroquinolones,” for their excellent Strep. pneumoniae coverage. The ophthalmic fluoroquinolones are also divided into two categories. The earlier-generation topical agents include ciprofloxacin and ofloxacin. The newer “fourth-generation” topical fluoroquinolones include besifloxacin, moxifloxacin, levofloxacin and gatifloxacin.22-26

Ciprofloxacin. This earlier-generation agent is another frequently used oral fluoroquinolone. While it no longer provides reliable Strep. pneumoniae coverage, it does have relatively good efficacy against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Both ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin have decent coverage against Haemophilus influenzae but no appreciable MRSA coverage.

Levofloxacin. Due to the differences in spectrum of coverage between ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin, ocular infections are generally treated with levofloxacin if and when a fluoroquinolone is necessary. If a pseudomonal infection is suspected or confirmed, consider ciprofloxacin instead. While levofloxacin may have sufficient pseudomonal coverage, it should be reserved for gram-positive infections to decrease potential resistance issues.11,19-26

Table 5. Oral Fluoroquinolone Dosing | |

| Levofloxacin | 500mg daily x 10 days |

| Moxifloxacin | 400mg daily x 10 days |

| Gemifloxacin | 320mg daily x 5 days* |

| Ciprofloxacin | 500mg to 750mg BID x 10 days** |

| * Coverage for resistant S. pneumoniae may not be sufficient.20-21,27-28 ** Choose only if P. aeruginosa is suspected or documented.19-21 | |

Gemifloxacin and moxifloxacin. As members of the “respiratory fluoroquinolone” group, gemifloxacin and moxifloxacin have bacterial coverage similar to levofloxacin. Occasionally, a Strep. pneumoniae isolate may be more sensitive to one agent than another in this group; however, they are generally considered fairly equivalent from an empiric treatment perspective. In some situations levofloxacin and moxifloxacin may have slightly broader coverage against highly resistant Strep. species. While less well known, both gemifloxacin and levofloxacin are generally considered interchangeable with levofloxacin in the management of gram-positive infections. Levofloxacin has slightly improved gram-negative activity.20,21,27,28

A Word About ResistanceAntibacterial resistance has been a concern since World War II, when we saw our first global distribution of penicillin. At the core of this problem lies the inability of practitioners to recognize how their individual prescribing practices can and will directly impact the future success or failure of antibiotics. Additionally, evolving organisms are growing resistant to antibiotics much faster than the rate at which we are able to produce new antibiotics to fight them. As physicians, it’s our responsibility to practice discretion when managing infectious diseases, in hopes of preventing—at all costs—the rise of antibiotic-resistant organisms. This should be done by avoiding the use of antibiotics for infections that are likely of viral origin and by choosing narrow-spectrum antibiotics at therapeutic doses for appropriate durations of treatment.34,35 |

These drugs are bacterial DNA synthesis inhibitors. It’s generally accepted that fluoroquinolones have chelation drug interactions, which result in a decrease in systemic absorption when the drug is given with di- and trivalent cations (e.g., multivitamins, calcium, iron). As such, any dietary supplements that are cations should be given either two hours prior or four hours after the fluoroquinolone.19-26

Adverse effects associated with fluoroquinolone antibiotics are perhaps their most notable drawback. They are generally contraindicated in pregnancy, breastfeeding and in children younger than 18 years old, due to the corresponding risk of arthropathy.20,21 Photosensitivity of the skin, resulting from all fluoroquinolones (and QT prolongation from the respiratory fluoroquinolones) are listed as potential side effects for these agents as well.20,21

Additionally, the risk of tendon rupture in the shoulder and Achilles has been well documented; it seems more likely to occur in elderly patients and in those taking systemic corticosteroids.31 While practitioners once suspected a correlation between fluoroquinolone use and the presence of a retinal detachment, newer research has debunked this.36 Additional research and clinical anecdotes will further determine the severity of this risk.32,33

The expanding role of the optometrist requires a multi-dimensional perspective on the treatment of infections that typically require systemic therapy. Additionally, staying current on resistance patterns, drug interactions and side effects is critical to one’s ability to choose the appropriate agent as well as one that will best encourage patient compliance.

Dr. Offerdahl-McGowan is an assistant professor of biomedicine at Salus University.

Dr. Caldwell is an ocular disease consultant in Duncansville and Johnstown, PA, and a past president of the Pennsylvania Optometric Association.

1. Morrow G, Abbott R. Conjunctivitis. Am Fam Physician. 1998;57(4):735-46. |