|

A 65-year-old white male presented to the emergency room for an evaluation of acute vision loss in his right eye. He said that, while playing golf early in the morning, his vision started to “white out.” Although his vision began to return that afternoon, his acuities were still decreased, prompting him to visit the emergency room. Initial testing revealed his blood pressure was elevated at 180/90. A computerized tomography scan of his brain was unremarkable, at which point we were consulted.

Emergent Workup

Upon examination, our patient denied any pain or neurologic symptoms associated with his vision loss. He denied scalp tenderness, headache or jaw claudication, symptoms of giant cell arteritis (GCA). At a recent visit, his internist told him he had borderline hypertension and cholesterol levels. At that time he was not started on any medication and was instructed to change his diet and engage in exercise.

The patient’s visual acuities were recorded to be 20/100 OD and 20/20 OS. We noted a trace afferent pupillary defect in his right eye.

Anterior and posterior segment exams were both unremarkable, and we noted no vitreous hemorrhage, disc edema, vein occlusion, retinal detachment or maculopathy. The retina seemed well perfused at this point, with no emboli present; however, the patient’s symptoms, recent vascular issues and absence of other clinical findings were highly suspicious for a possible diagnosis of reperfusing central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO).

We admitted the patient and ordered a complete blood count (CBC), complete metabolic panel (CMP), lipid profile, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and c-reactive protein (CRP), as well as an MRI of the brain, MRA of the head and neck, and an echocardiogram. We also discussed the case with the attending physician and recommended the patient be treated for his elevated blood pressure.

|

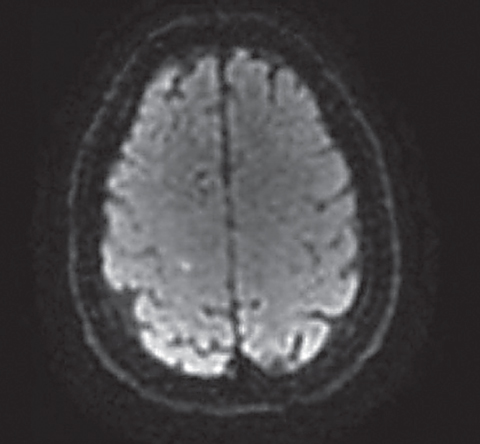

| On MRI, a punctate acute stroke is noted along the medial aspect of the right central sulcus. |

Diagnosis

Upon re-examination 24 hours later, his visual acuity had improved to 20/50 OD. MRI revealed a punctate acute stroke along the medial aspect of the right central sulcus, and MRA revealed 30% stenosis of the proximal right internal carotid artery secondary to an atherosclerotic plaque. The patient’s total cholesterol and LDLs were both slightly elevated; CBC, CMP, ESR and CRP were normal and echocardiogram showed mild tricuspid valve regurgitation.

Our patient was diagnosed with a probable CRAO with an acute cerebrovascular accident (CVA) secondary to an atherosclerotic plaque of the right internal carotid artery. He was started on lisinopril, atorvastatin and clopidogrel and discharged two days later after cardiology and neurology determined he was stable.

Follow Up

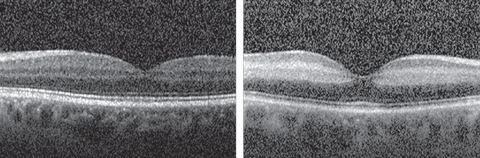

On examination one week later, the patient’s acuity was stable at 20/50 OD. Macular spectral-domain optical coherence tomography showed nerve fiber layer thickening consistent with the acute phase of a CRAO, and fluorescein angiography showed a delay in the filling time of the right eye’s retinal arteries; the results of both tests were consistent with our diagnosis. We noted no additional clinical findings, and he was stable from an ocular perspective.

We instructed him to continue to follow up with his internal medicine, cardiology and neurology doctors for management of his underlying vascular issues and we will monitor him with dilated fundus examinations every three to six months.

|

| The increased reflectivity and thickening of the right eye’s nerve fiber layer (at right) is consistent with the acute phase of a retinal artery occlusion, contrasted with the appearance of the normal nerve fiber layer (at left) in the patient’s left eye. Click image to enlarge. |

Discussion

Although our patient was fortunate, the visual prognosis is generally quite poor for an eye that develops a retinal artery occlusion (RAO). Certain in-office procedures, such as digital massage and anterior chamber paracentesis, can help push through emboli and re-perfuse the retina, but the success of these techniques is quite limited. Therefore, the major goal in managing RAOs has always been to identify the underlying cause and prevent any future episodes, especially to the good eye.

RAOs are most commonly embolic in nature, but they may also result from vasculitic disorders or hypercoagulopathies.1 Historically, the recommended workup included an examination with the patient’s general practitioner, carotid artery ultrasound, echocardiogram and lipid profile within one to two weeks in an outpatient setting.1 Additionally, an ESR and CRP were recommended if patients presenting with CRAO were older or present with symptoms suggestive of GCA as well as evaluation of coagulopathies when suspicious.

However, a number of recent studies reveal a significant link between retinal artery occlusion and acute stroke. In one study, 24.2% of subjects who presented with retinal artery occlusion had acute brain ischemia concurrently, where most of the infarction patterns were small, multiple and scattered.2 More alarming still, 37.5% of these subjects did not present with any neurologic symptoms or findings.2 In another study, researchers looked at the increased incidence of acute stroke and found similar results, with the peak incidence of these events occurring one to seven days after the presentation of the RAO.3

In light of these new findings, our management of retinal artery occlusion has changed significantly. Given the high risk and timing of acute CVA, instead of working up these individuals as outpatients, we are now sending them to the hospital for emergent admission and evaluation for stroke. Additionally, their workup is now much more extensive. These patients will require an MRI of the brain, MRA of the head and neck, echocardiogram, serologic studies to identify cardiovascular risk factors and neurology and cardiology consultations.

Workup for vasculitis and coagulopathies should also be performed when suspicious. Because the co-occurrence of RAO and CVA may not always be apparent, we strongly recommend eye care providers and hospital physicians communicate with one another for guidance regarding evaluation and management.

Although our patient went to the emergency room, often patients experiencing retinal artery occlusion will present to the optometrist’s office first. It is our responsibility to not only manage the RAO and any ocular morbidities but to also refer these patients for emergent stroke evaluation.

1. Varma DD, Lee AW, Chen CS. Central retinal artery occlusion: general overview, diagnosis, and treatment causing sudden vision loss, this rare but troubling condition is linked to cardiovascular disease. Ret Physic. 2013;10(9):24-9. |