11th Annual Pharmaceuticals ReportFollow the links below to read other articles from annual update on pharmaceuticals: Know Your Systemic Meds: The Top 10 to Track One Size Won't Fit All: Treating Ocular Infection Protocols and Pitfalls of Topical Steroid Use |

Dry eye disease (DED) is a multifactorial disorder of the ocular surface that severely impacts vision and quality of life. Risk factors that contribute to DED include age, gender, hormones, autoimmune disorders, local environment, use of video displays, contact lens wear and exposure to medications/preservatives, all potentially leading to secretory or evaporative DED, or both.1 Inflammation is another key risk factor. The Tear Film and Ocular Surface Society’s Dry Eye Workshop II definition recognizes the impact of inflammation, saying, “Dry eye is a multifactorial disease of the ocular surface characterized by a loss of homeostasis of the tear film, and accompanied by ocular symptoms, in which tear film instability and hyperosmolarity, ocular surface inflammation and damage, and neurosensory abnormalities play etiological roles.”

With this more finely honed understanding of DED in mind, optometrists must make controlling inflammation a priority. This article will review the optometrist’s role in diagnosing inflammation in the clinical setting, including options to best treat inflammatory dry eye disease with the tools currently available.

|

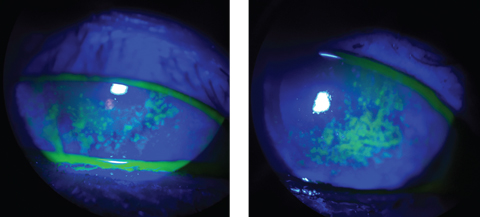

| The sodium fluorescein staining used in these patients reveals a compromised corneal surface due to DED. Click images to enlarge. |

Identification and Classification

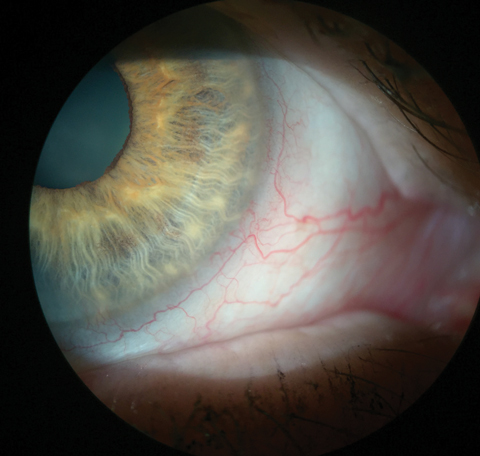

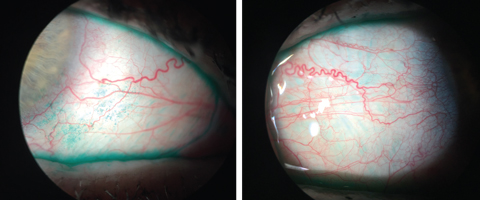

Inflammation on the ocular surface can be overt or covert in its presence. Conjunctival hyperemia, or redness, is a hallmark of ocular inflammation that can be objectively evaluated by anterior segment photography or with the use of grading scales, such as the Efron Grading Scales.2,3 Vital dyes are also valuable in the detection of ocular surface damage often seen alongside inflammation. The use of sodium fluorescein or lissamine green vital dyes are particularly helpful in identifying and visualizing the devitalized cells on the conjunctiva.

Tear chemistry can also be associated with ocular surface inflammation. Using a system designed to measure tear osmolarity (e.g., TearLab Osmolarity System, or I-Pen [I-Med Pharma]) is one way to quantify inflammation. For patients without inflammation, their hyperosmolarity will read less than 300mOsm/L.1,4 With this quantification, physicians can engage their patients by providing pretreatment and post-treatment results. Research shows matrix metalloproteinases, specifically matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9), is a byproduct of inflammation and cell insult and, now that an MMP-9 detection test (e.g., InflammaDry Detector, Quidel) is available, we can count that as yet another biomarker of inflammation.1,5

The clinical symptoms of inflammation include end-of-day burning, stinging, dry, irritated, scratchy, watery and itchy eyes.2 If a patient presents with these clinical signs and symptoms, therapeutic intervention is indicated. As soon as patients can be categorized as mild-to-moderate—by either exhibiting corneal staining signs, decreased tear film break-up time or complaining of DED symptoms—anti-inflammatory medications are justified.

|

| This patient’s injected blood vessels indicate inflammation. In this eye, it can be seen without any vital dyes. Click image to enlarge. |

The Right Stuff

When deciding which anti-inflammatory to use, keep in mind each drug’s mechanisms of action.

Corticosteroids act on various inflammatory responses, including intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1)-mediated cell adhesion, cytokines/chemokines/MMPs expression and induction of lymphocyte apoptosis.6-8 Simply put, corticosteroids have a broad-spectrum mechanism of action when it comes to controlling inflammation. However, their long-term use in ocular conditions is not recommended because of steroid-related side-effects such as increased intraocular pressure and cataract formation.9 Thankfully, not all corticosteroids are created equal. A “soft” steroid such as loteprednol or fluorometholone could be used for four to six weeks without having to worry about the long-term side effects. Sometimes I will also pulse the soft steroid BID to TID dosage for one week on and two weeks off, then repeat as needed with close clinical follow ups.

Cyclosporine (CsA) is another anti-inflammatory medication used to combat inflammation associated with DED. In a large multicenter study, 0.05% to 0.1% CsA treatment significantly reduced HLA-DR expression and to a lesser extent expression of other inflammatory and apoptotic markers in patients with moderate-to-severe DED.10,11 Topical CsA increase goblet cell density and conjunctival production of immunomodulatory transforming growth factor beta-2 (TGF-ß2) in DED patients.12 In 2003, Restasis (topical cyclosporine 0.05%, Allergan) received approval from the FDA to increase tear production in patients whose tear production is presumed to be suppressed due to ocular inflammation associated with keratoconjunctivitis sicca.1 Because of the mechanism of action of CsA, the anti-inflammatory effects usually won’t take place until after at least four to six weeks of starting therapy.10,11 This won’t be the best medication to use if you have a patient with acute inflammation. Also because of the immunomodulator properties of CsA, it is a good option to treat autoimmune disease associated dry eyes, such as Sjögren’s syndrome.

Lifitegrast is an anti-inflammatory drug that was approved by the FDA in 2016 for the treatment of the signs and symptoms of DED. Xiidra (topical lifitegrast 5%, Shire) is the first dry eye medication that targets integrin signaling as a lymphocyte function-associated antigen-1 (LFA-1) antagonist that blocks coupling of LFA-1 and ICAM-1.13 LFA-1 is found on the surface of the T-cell. By blocking the interaction between LFA-1 and ICAM-1, it is thought that one of the inflammatory cycle is prevented. In the OPUS-1 clinical study, there was a significant improvement in signs such as inferior corneal staining, but not in symptoms.14 The subsequent OPUS-2 study established significant improvement in the eye dryness score, and this was confirmed in OPUS-3.15,16 Symptomatic relief occurred as early as two weeks after initiating treatment for patients with moderate DED.

After determining the severity of the inflammation in a DED patient, whether by having a positive response to the InflammaDry test, or by simply grading the clinical signs; the optometrist can then decide if a topical steroid is needed to quickly decrease the overall inflammation along with either Restasis or Xiidra. If the inflammation is particularly severe, you might considering using a soft steroid with both Restasis and Xiidra together, as their mechanisms of action are different. However, if the inflammation isn’t so severe it requires a topical steroid, lifitegrast (for faster symptom relief) and CsA (if the patient has autoimmune disease associated DED) without the steroid is acceptable.

|

| The lissamine green staining here highlights the devitalized cells on the conjunctiva, which indicate ocular surface disease. Click images to enlarge. |

Complementary Treatments

Controlling inflammation is a vital step in reducing DED symptoms, but optometrists can also treat mechanical issues that can be (but aren’t always) the root cause of dry eye. For instance, patients with meibomian gland dysfunction have obstructed glands and may be able to find relief once they are unclogged. A conservative approach involves using heat therapy in the form of a warm compress that is directly applied to the lids to try to reduce the viscosity of the meibum within. A more aggressive approach involves in-office treatments, such as Lipiflow (Tearscience), a thermal pulsation device that simultaneously heats the meibum and pulsates to liberate the melted meibum out of the glands.

Diet is another aspect in which we can directly affect the level of inflammation in the eye. Oral supplementation with omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, eicosapentaenoic acid or docosahexaenoic acid found in fish oil all decrease the production of pro-inflammatory mediators, such as prostaglandin E2, and cytokines.18 Gamma-linolenic acid (GLA) is also an omega-6 with anti inflammatory properties.19 HydroEye (Science Based Health) provides the necessary GLA formulation through black currant seed oil.

Another contributor to inflammation is blepharitis from the lids.20 The etiology of the condition is not fully understood, but low-grade bacterial infection (primarily Staphylococcus), Demodex mites, environmental factors and certain systemic disease have all been implicated as potential contributors.20

The Combo Approach

Topical antibiotic-corticosteroid combination products are useful for decreasing the bacterial load as well as managing the inflammation.20 Concerns of antibiotic resistance and long-term exposure to the corticosteroids comes to mind when using these type of medications. After a short course of a topical antibiotic-corticosteroid combo medication, you may want to switch the patient to a type of hypochlorous acid (HOCl) cleanser such as Avenova (NovaBay) or Acuicyn (Sonoma Pharmaceuticals) to keep the bacterial levels at bay.21 HOCl is a natural product made by neutrophils to kill microorganisms.22 Oral doxycycline is another tool that can be used to control inflammation via MMP suppression.23 A maintenance dose of 50mg BID can be prescribed for up to three months to try to control the inflammation systemically.

Topical steroids should not be used long-term without frequent monitoring because of the potential side effects. They can be used initially to control the acute stage of inflammation and then tapered off. CsA in the form of Restasis is safe to use long term but requires continued use to achieve its anti-inflammatory properties and also can take up to two months before noticing any improvement in DED symptoms.24 Xiidra is also safe to use long term and can work on the current inflammatory response for faster resolution.15,16

Dr. Dang is an optometrist practicing in a multi-speciality eye clinic in Bakersfield, California. His clinical practice covers a broad spectrum of ocular care with a unique clinical focus on ocular surface disease and dry eye.

1. Baudouin C, Irkeç M, Messmer E, et al. Clinical impact of inflammation in dry eye disease: proceedings of the ODISSEY group meeting. Acta Ophthalmol. 2018 Mar;96(2):111-119. |