As optometrists, we see patients with dry eye disease (DED) on a daily basis. Although we now understand how prevalent DED can be, we sometimes forget that a dry eye diagnosis isn’t always the end of the story. Eye care providers need to start paying closer attention to underlying systemic conditions such as Sjögren’s syndrome (SS) that might exacerbate patients’ dry eye signs and symptoms.

|

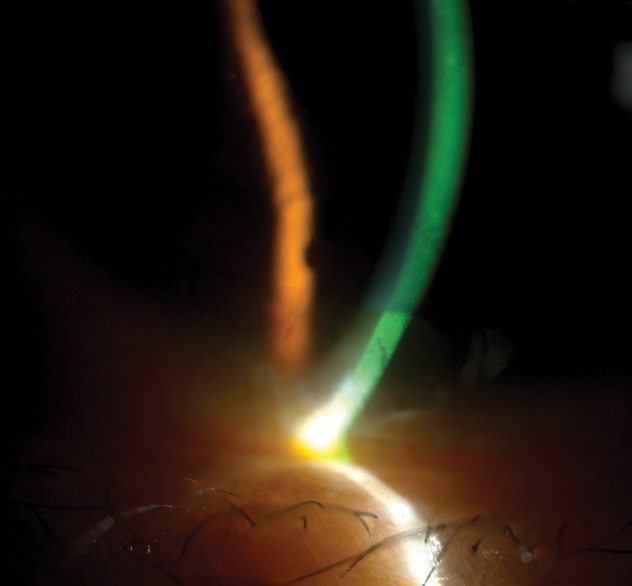

| This Sjögren’s patient with significant dry eye has diffuse inferior superficial punctate keratitis. |

SS is the second most common autoimmune rheumatic disease, affecting between three and six per 100,000 Americans.1 The peak incidence is between the ages of 40 and 60, with a higher predilection in women than men (9 to 1).2 As optometrists, it is inevitable some of your DED patients will need extra care because of this underlying condition. Most challenging is the fact that a dry eye diagnosis in patients with SS can precede systemic symptoms and complications by almost 10 years.3 This article reviews the basics of SS, the diagnostic challenges and clinical pointers for dry eye management.

SS Basics

Autoimmune diseases arise from an immune response against endogenous tissues. SS in particular targets the exocrine glands of mucous membranes and is often referred to as an “autoimmune epithelitis.”4 The autoimmune response in Sjögren’s occurs from mononuclear infiltration of the salivary and lacrimal glands, leading to the hallmark complaints of dry mouth and dry eyes. However, many parts of the body can be affected, leading to complaints of joint and muscle pain, skin rashes, chronic dry cough, vaginal dryness, extremity numbness or tingling and fatigue.3,5 These symptoms can occur years after the onset of the ocular and oral symptoms, and almost 60% of patients presenting with primary Sjögren’s develop these symptoms eventually.3,5

SS can be divided into two categories: primary and secondary. In primary SS, the individual has no secondary disease causing the SS. With secondary Sjögren’s, the disease occurs in conjunction with another autoimmune disease, such as rheumatoid arthritis or systemic erythematous lupus.5

|

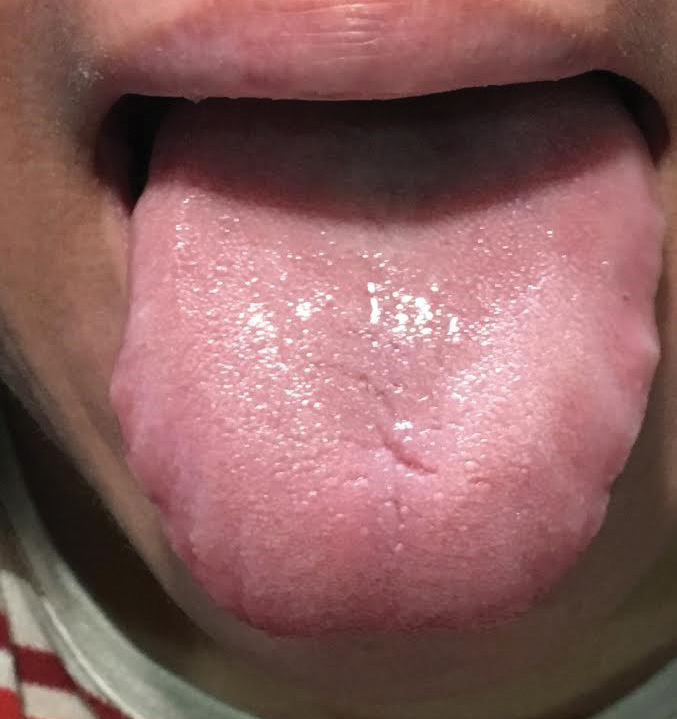

| This patient with both SS and lupus has central fluorescein staining. The central coalesced superficial punctate keratitis is causing decreased vision and discomfort. Click image to enlarge. |

As with other autoimmune diseases, SS involves both genetic and environmental factors.6 The largest genetic predisposition to SS is the human leukocyte antigen, specifically HLA B-8, HLA DR-w2 in women and HLA DR-w3 in men.2 Roughly 10% to 15% of patients with Sjögren’s will have systemic extraglandular manifestations due to lymphocytic infiltration surrounding the epithelium of target organs—such as the liver, kidneys and bronchi—and can present with the clinical picture of vasculitis, arthralgia or arthritis.7 When examining these patients, clinicians should check their skin, as cutaneous involvement is common and can present as xeroderma in 67% of patients, eyelid dermatitis in 40%, annular erythema in 9% and cutaneous vasculitis in 5% to 10% of patients with Sjögren’s.2

Additional symptoms of fatigue, depression, myalgia and arthralgia can affect patients’ quality of life both before and after an SS diagnosis.3,8 Patients with SS also have increased risk of cerebrovascular events, myocardial infarction, arthritis, neuropathies and vasculopathies, Raynaud’s phenomenon, pulmonary fibrosis, renal tubular acidosis and, due to internal organ damage, lymphomas, specifically non-Hodgkin B-cell lymphoma.8,9

Table 1. 2012 ACR Proposed Classification Criteria for SS3 |

| The classification of Sjögren’s syndrome will be met in patients who have at least two of the following three objective features: |

| 1. Positive serum anti-SS-A/Ro, anti-SS-B/La or positive rheumatoid factor and ANA >1:320 |

| 2. Labial salivary gland biopsy exhibiting focal lymphocytic sialadenitis with a focus score >1 focus/4mm2 |

| 3. Keratoconjunctivitis sicca with ocular staining score >3 (assuming the individual is not currently using daily eye drops for glaucoma and has not had corneal surgery or cosmetic eyelid surgery in the last five years) |

Diagnostic Puzzle

SS diagnosis can be difficult because of the associated symptoms and comorbidities.8 Experts have sought to create diagnostic guidelines for patient inclusion in clinical and research trials. The American-European Consensus Group (AECG) developed a criteria in 2002 for use in clinical trials with the following parameters: subjective ocular and oral dryness, dry eye testing using Schirmer’s test, reduced salivary flow, positive salivary gland biopsy and positive autoantibodies against SS-A and SS-B, with the last two as mandatory requirements.10,11

The American College of Rheumatology (ACR), in conjunction with the Sjögren’s Collaborative Clinical Alliance (SICCA), established a different guideline for clinical research in 2012. This eliminated the subjective complaints, requiring two out of three objective measurements: (1) biomarker positivity (Ro or La) or positive rheumatoid factor (RF), (2) antinuclear antigen (ANA) or labial salivary gland biopsy findings and (3) keratoconjunctivits sicca (Table 1).3 Between the AECG and ACR guidelines, the AECG identified more SS patients, but the ACR was able to identify Sjögren’s patients earlier.10

In 2016, the ACR and the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) combined both the AECG and ACR guidelines to form a new standard for research practices.12 The new guidelines also included systemic manifestations and sicca symptoms with a weighted score assigned to each parameter including: positive salivary gland, anti-SSA/Ro-positive, ocular staining, Schirmer’s test, salivary flow rate (Table 2).3,5 A diagnosis is made after patients scored four or greater based on the guidelines. The AECG and the ACR/EULAR guidelines showed a good correlation and consensus in diagnosing SS in clinical and research trials, with an increase in early diagnosis with the ACR/EULAR guidelines.12

Biopsy of the minor salivary glands remains the most specific test to diagnose Sjögren’s syndrome and is a necessary component for the AECG and ACR guidelines.3 Though invasive, a biopsy is specific for SS; however, damage may have already occurred in the glandular systems.3 It is important that the salivary gland biopsy be performed by a trained professional and be reviewed by an experienced pathologist.3 Two noninvasive procedures, salivary gland ultrasonography and acoustic radiation force impulse of the parotid and submandibular glands, can also aid in identifying anatomical and functional damage in patients diagnosed with SS.3,13

Table 2. 2016 ACR/EULAR Primary SS Classification Criteria3,5 | |

| Item | Score |

| Labial salivary gland with focal lympocytic sialadenitis and focus score >1 foci/4mm2 | 3 |

| Anti-SSA/Ro positive | 3 |

| Ocular staining score <5 (or van Bijsterveld score <4) in a least one eye | 1 |

| Schirmer’s test <5mm/5min in at least one eye | 1 |

| Unstimulated whole salvia flow rate <0.1mL/min | 1 |

| The classification of primary SS applies to any individual who meets the inclusion criteria, does not have any of the exclusion criteria and has a score of greater than or equal to 4. | |

Inclusion criteria

| |

Exclusion criteria

| |

SS in Your Office

DED is one of the hallmark signs of SS, which requires optometrists to be an integral part of identifying and comanaging the disease. Since ocular symptoms can precede the systemic effects of SS, diagnosing DED can often be the first step in identifying SS in a patient. Clinicians should suspect SS when patients present with difficult dry eye, inflammation and dry mouth.14 Aqueous DED (ADDE) is commonly associated with SS because T-cells attack the lacrimal glands, resulting in cell death and tear hyposecretion.14 SS patients also have a poor mean meiboscore and meibomian gland expressability compared with non-SS dry eye patients, indicating a correlation between SS and evaporative DED (EDE).9

In the clinical setting, ODs know dry eye can adversely affect patients’ quality of life. Those with SS report functional disability comparable with patients affected by lupus.8 Surveys and questionnaires can help clinicians form a subjective understanding of patients’ dry eye symptoms to help tailor treatment appropriately. The Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI) correlates the symptoms of DED with its effect on visual function and can be incorporated into clinical practice to successfully grade the degree of DED from normal, mild to moderate and severe.15,16 The McMonnies questionnaire, the Standard Patient Evaluation of Eye Dryness questionnaire, the Symptom Assessment in Dry Eye survey and the Impact of Dry Eye on Everyday Life survey are a few other questionnaires that are also used for clinical and research trials.17 Though questionnaires can provide valuable information, they are not enough to confirm a diagnosis of DED or SS.18

|

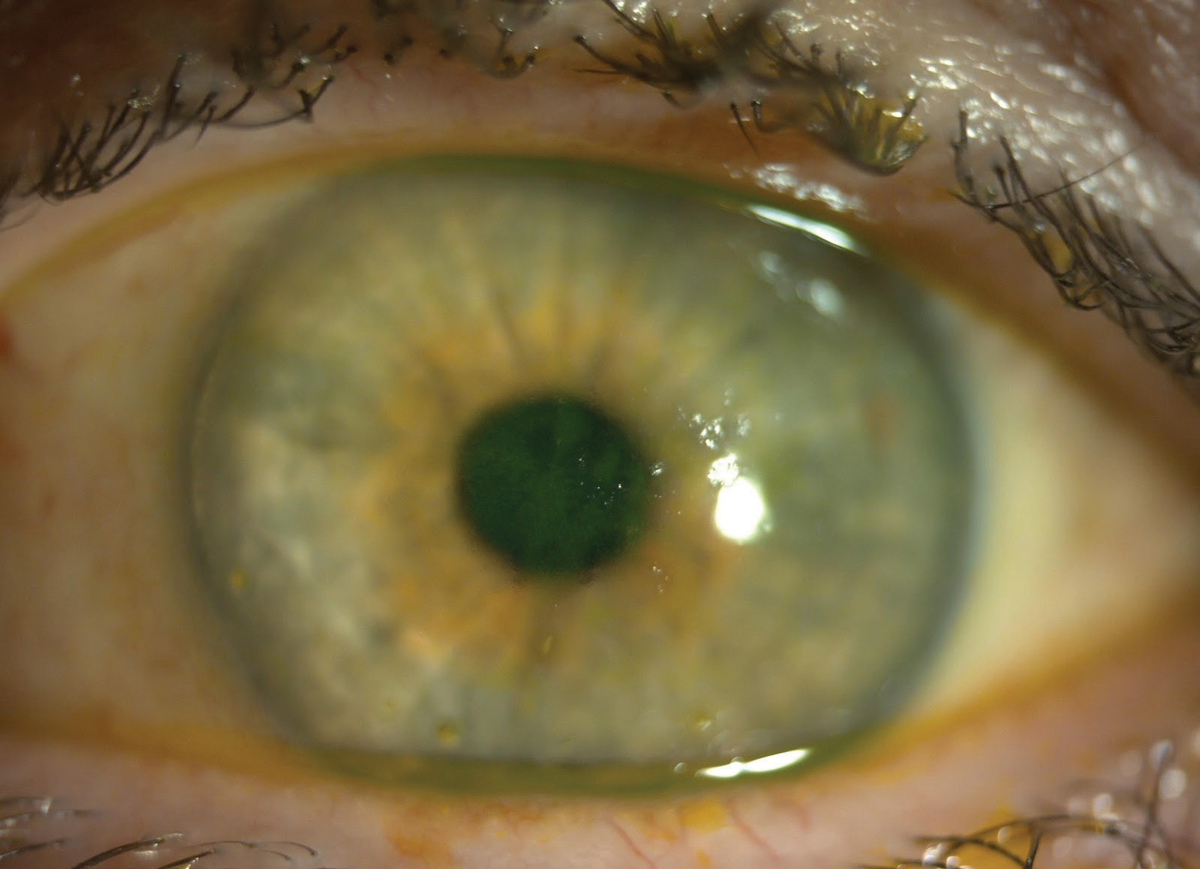

| It is important to examine skin and cutaneous involvement. A patient may have a sore, cracked tongue that can be suggestive of Sjögren’s. |

Using the OSDI, clinicians can connect patient responses with clinical findings. Patients often complain of burning, stinging, foreign body sensation, itching, pain and blurred vision with some improvement upon blinking. Tear film irregularities show a decreased tear meniscus; instead of the normal 1mm, dry eye patients will have a reduced tear strip.18 Thus, ocular dyes and tear secretion tests, such as Schirmer’s test, can help diagnose DED. The tear film and conjunctiva are best evaluated through the use of fluorescein, rose Bengal and lissamine green vital dyes. With fluorescein, the tear film is assessed for dark spots, which indicate the tear break-up time (TBUT). Normal TBUT is greater than 10 seconds, and anything less than 10 seconds is indicative of DED.14,17 Schirmer’s test measures total tear secretion rate, therefore differentiating between ADDE and EDE, as ADDE occurs due to lacrimal gland dysfunction.16 Schirmer’s test without topical anesthetic quantifies reflex tear secretion, while testing with topical anesthetic quantifies basal tears. A patient tests positive for DED with measurements of <5mm to 7mm for reflex tear secretion and <3mm for basal secretion.14,17

The Sjö test (Bausch + Lomb) is a billable laboratory or in-office blood test for biomarkers specific for SS, including the traditional SS biomarkers anti-SS-A/R0, anti-SS-B/La, ANA, and RF, as well as new biomarkers such as salivary gland protein-1, parotid secretory protein and carbonic anhydrase VI.3,14 If results return positive for SS, refer the patient to a rheumatologist for further management and testing. The addition of the new biomarkers allows for better sensitivity and specificity because of their possible early detection of SS.3 Case reports show patients who had an early diagnosis of SS tested positive for the new biomarkers after they had already tested negative for the traditional biomarkers.3

|

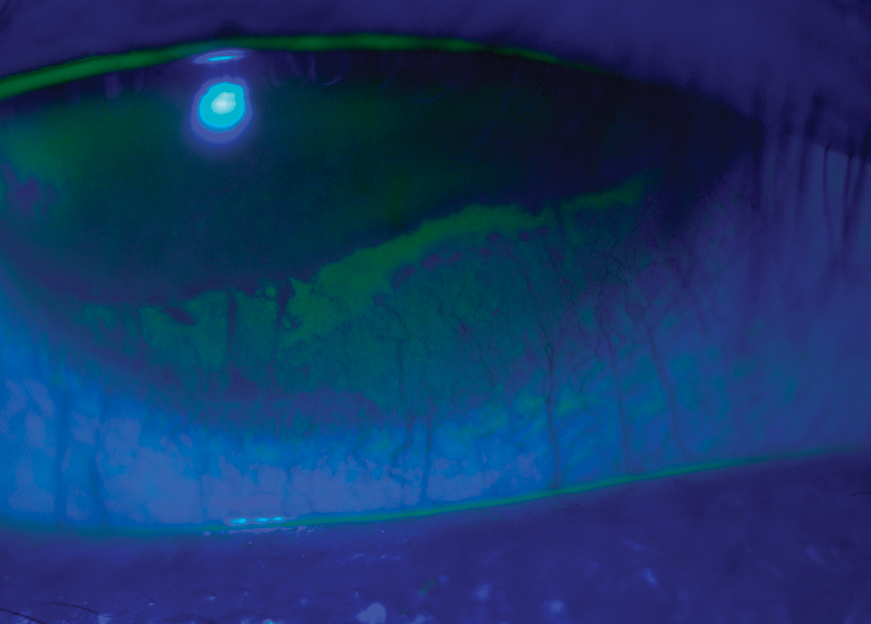

| Before being diagnosed with SS, this gas permeable contact lens wearer presented complaining of severe dry eye, dry mouth and vaginal dryness. This image shows her severe dry eye and superficial punctate keratitis along the entire lower half of her cornea. She experienced some relief with Xiidra and punctal plugs. |

Treatment

With no cure for SS, the therapeutic goals are aimed toward eliminating the hallmark complaints of dry eye and dry mouth. Clinicians should target treatment based on the severity of the disease. Mild dry eye can be alleviated with simple changes, such as modifying the environment (e.g., reducing time spent in dry or windy environments). Other methods include eyelid hygiene and following a diet high in omega-3 fatty acids.17

As DED progresses beyond what these simple changes can manage, artificial tears become the first line of therapy. The ingredients in artificial tears, mainly a polymeric base or a viscosity agent, are designed to increase the amount of time the tears are on the ocular surface, thereby increasing the tear meniscus.17 Different classes of artificial tears have different formulations, and some may work better with certain patients. For example, some contain potassium and bicarbonate ions while others are designed to configure the lipid portion of the tear film.17 Although no studies prove any particular artificial tear is superior, specific ingredients to watch out for include preservatives such as benzalkonium chloride and EDTA, which can be toxic and worsen dry eye. Gel tears and ophthalmic ointments are thicker and last longer on the ocular surface, but can cause temporary blurred vision. Ointments are best reserved for nighttime use and can help to relieve dry eye symptoms during sleep.

The Tear Film and Ocular Surface Society’s Dry Eye Workshop II report includes “inflammation of the ocular surface” in its definition of DED, and studies show the presence of inflammatory cells, such as lymphocytes in the ocular surface.14 Anti-inflammatory drops help control the inflammatory response in keratoconjunctivitis sicca, especially in patients with moderate to severe dry eye that present with SS. Although cases show subjective and objective improvement in dry eye symptoms and signs with corticosteroids, the possible side effects of elevated intraocular pressure and posterior subcapsular cataracts deter long-term use.

Restasis (cyclosporine, Allergan) is FDA-approved to treat moderate to severe DED, and studies show significant improvement in corneal signs, such as fluorescein staining and increased tear production, after using cyclosporine 0.05%; as many as 59% of patients had increased tear production.17 Burning is one of the side effects of cyclosporine use, which can be alleviated by a low-dose steroid during the first two weeks of use.17 Studies have yet to show any contraindication in using cyclosporine for an extended period; after three years, patients did not report any adverse effects.17

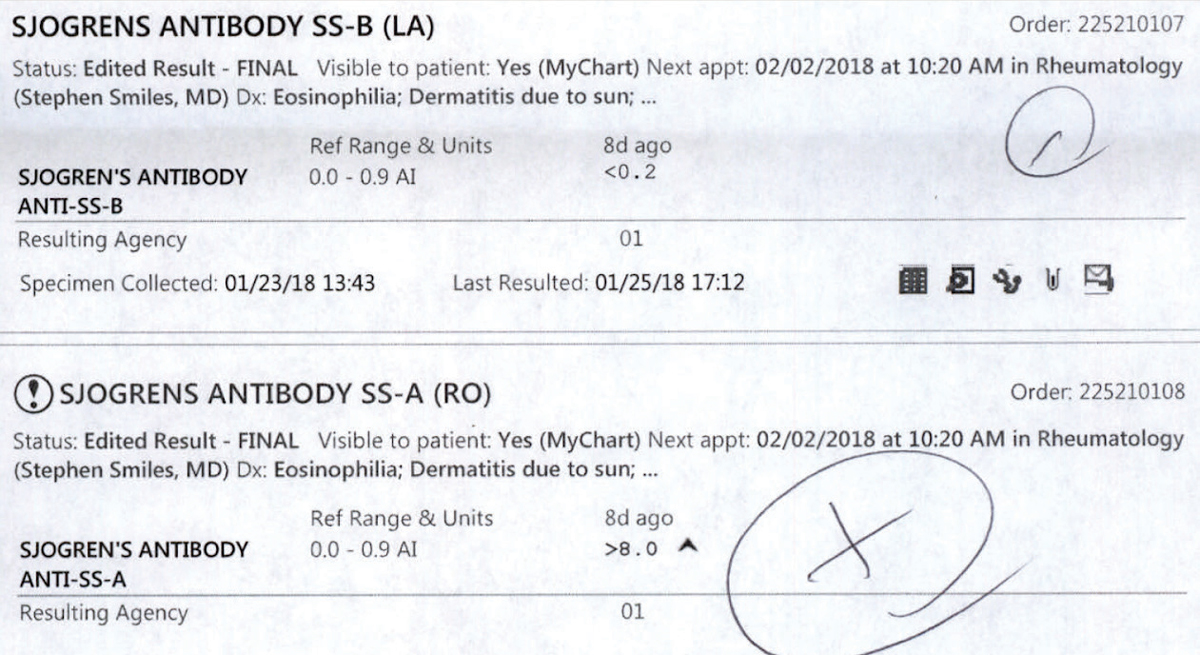

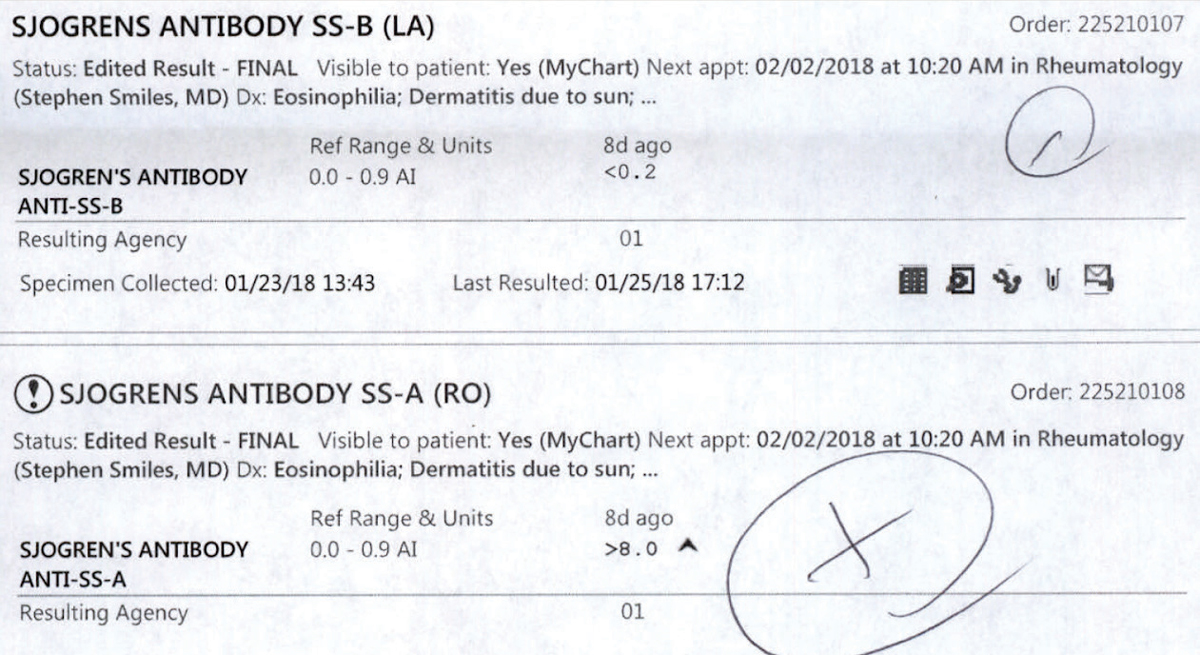

|

| These lab results for a patient sent for Sjögren’s bloodwork are postitive for SS-B and SS-A antibodies. Click image to enlarge. |

Xiidra (lifitegrast, Shire), also FDA-approved for treatment of DED, inhibits inflammatory cells and affects the T-cell mediated immune response, thereby decreasing inflammation.14 Early trials show improvement in corneal staining and subjective complaints in dry eye symptoms; however, since it is a newer medication, long-term studies are pending.14 Possible side effects include ocular burning and dysgeusia, or a change in taste sensation.19

Punctal plugs remain a popular option for treating DED. Their purpose is to retain natural and artificial tears on the eye for a longer period. Studies show improvement in clinical signs and subjective improvement, such as through the OSDI questionnaire, after punctal occlusion. It is important to understand with punctal occlusion there will be an increase in pro-inflammatory cells on the ocular surface.20

Other, less common therapies include secretagogues and autologous serum. In the case of secretagogues for SS, oral pilocarpine and cevimeline cause tear secretion from the lacrimal gland and saliva from the salivary glands. Salagen (MGI Pharma) and Evoxac (Daiichi Sankyo) are secretagogues approved for treatment of dry mouth, but not specifically for dry eye; however, off-label use shows improvement in dry eye symptoms and clinical signs.17 Autologous serum can be used for severe dry eye patients who have exhausted all other treatments without improvement. The patient’s own blood is used to create the serum because the shared biochemistry between the serum and natural tears improves efficacy.17 The serum has a host of components that aid in improving the ocular surface, including fibronectin, vitamin A, cytokines, growth factors and anti-inflammatory factors.17 Research shows symptoms and corneal signs improve after using autologous serum, although careful handling is important to prevent infections due to contamination.17

To properly manage and treat DED associated with SS, clinicians must understand the systemic disease as a whole. SS should be a priority in our differentials for patients with DED. By looking at all relatable symptoms, including any secondary autoimmune disease and specific complaints of a dry, cracked tongue, clinicians can help to diagnose SS sooner and initiate treatment in a timely manner. Because SS is also associated with comorbidities such as depression and fatigue, an early diagnosis and subsequent treatment will allow patients an improved quality of life.

Prompt referral to and comanagement with rheumatology will help provide the appropriate care for the patient. Autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and systemic erythematous lupus that occur concurrently with SS will need to be managed by rheumatology as well. Anti-rheumatic drugs used for these autoimmune diseases have also shown beneficial for those diagnosed with SS.8

Treating and managing these patients may seem systematic, with lifestyle modifications and artificial tears as initial starters; however, each patient will respond differently to treatment. Therapy must be modified as signs or symptoms change, but relieving subjective and objective complaints will remain imperative to improving quality of life.

Dr. Sherman is an instructor in Optometric Science (in Ophthalmology) at Columbia University Medical Center, NY. She specializes in complex and medically necessary contact lens fittings and ocular disease.

Dr. Shuja is an optometrist at New York-Presbyterian Hospital.

1. Jonsson R, Vogelsang P, Volchenkov R, et al. The complexity of Sjögren’s syndrome: Novel aspects on pathogenesis. Immunology Letters. 2011;141(1):1-9. |