|

A 53-year-old Hispanic female presented with intermittent ocular irritation and itchiness in both eyes for the past year. She does not use any drops. In addition, she reported transient episodes of dimming vision, and sometimes her vision even gets dark for several seconds. This started six months ago and happens about once a week. She felt this was occurring in both eyes.

Her medical history was significant for well-controlled hypertension. She was on amlodipine, atenolol, enalapril and lisinopril. She also reported having had brain surgery in the early 1990s in Nicaragua for removal of a frontal lobe tumor. She felt like she fully recovered from this operation and did not have any lasting effects.

On examination, her entering visual acuity with glasses measured 20/20 OU at distance and near. Confrontation visual fields were full-to-careful finger counting in both eyes. Her ocular motility testing was normal, and the pupils were equally round and reactive without an afferent pupillary defect. The anterior segment was unremarkable. Intraocular pressures measured 19mm Hg OU.

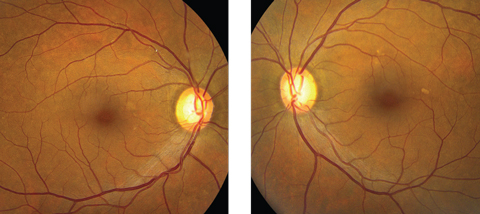

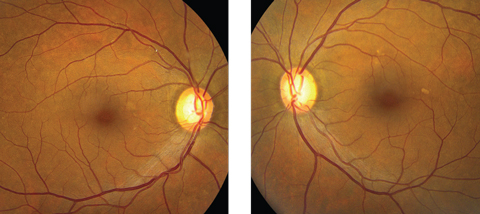

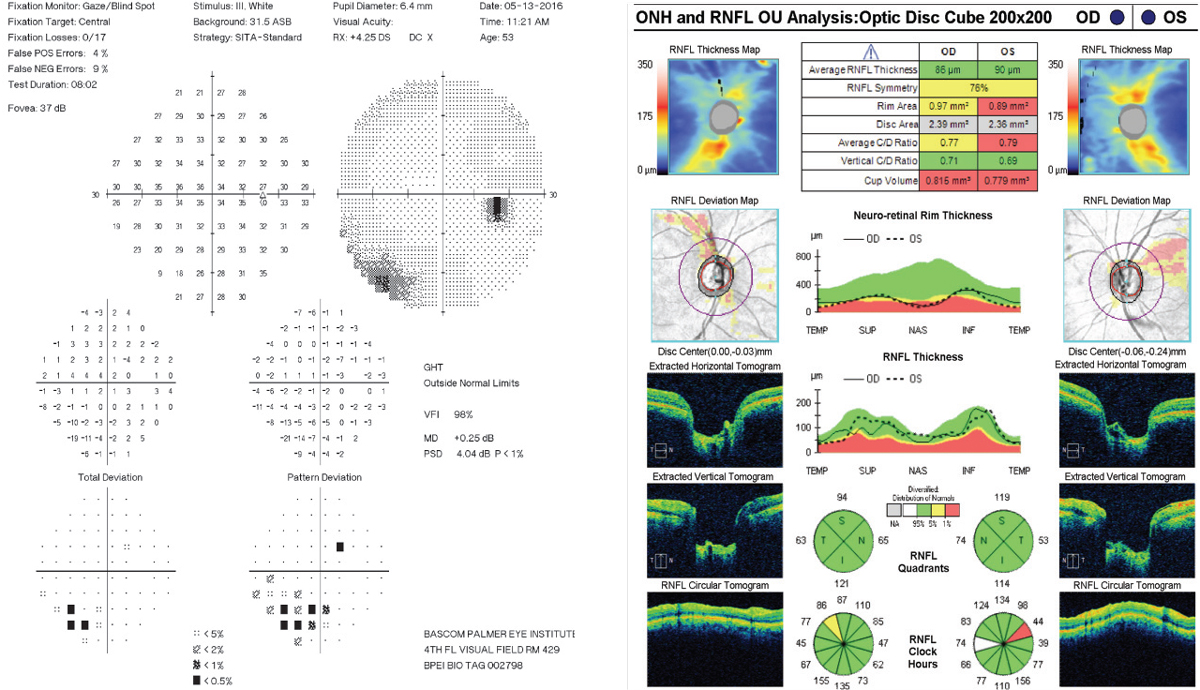

Her dilated fundus exam showed changes (Figure 1). An OCT and visual field was also obtained and is also available for review (Figures 2).

|

| Fig. 1. These fundus photographs show our 53-year-old Hispanic patient. Although her initial complaint was a red eye, can you identify any other pathology here? Click images to enlarge. |

Take the Retina Quiz

1. How would you describe the patient’s symptoms?

a. Usual presbyopia changes.

b. Transient ischemic attacks.

c. Amaurosis fugax.

d. Visual aura.

2. What is the significant finding seen in this patient?

a. Advanced optic nerve cupping.

b. Nerve fiber layer defects.

c. Thrombin in the retinal vein.

d. Cholesterol plaque in the retinal artery.

3. How would you classify these changes?

a. Calcific.

b. Thrombin.

c. Cholesterol.

d. Fibrin.

4. What is the correct diagnosis for this patient?

a. Whitman plaque.

b. Hollenhorst plaque.

c. Branch retinal artery occlusion.

d. Advanced glaucoma with nerve fiber layer defect.

5. How should this patient be managed?

a. Observation.

b. Immediate referral for carotid evaluation.

c. Begin treatment with prostaglandin eye drops for IOP control.

d. Visual field and OCT testing.

For answers, see below.

|

| Fig. 2. How do you explain the visual changes, at right, in the patient’s right eye? Based on the RNFL, could this patient have glaucoma? Click images to enlarge. |

Diagnosis

Our patient is describing symptoms consistent with amaurosis fugax, which is a transient loss of vision in one eye. It is usually fleeting, lasting seconds to minutes and results from transient retinal ischemia. It is most commonly due to an embolism or plaque from the ipsilateral carotid artery, but can occur from a number of other causes associated with transient ischemic attacks.1

If the plaque is small enough, it will continue to pass through the retinal circulation with zero to minimal noticeable effects on vision. Larger plaques can cause a complete blockage of the artery, which in turn can lead to severe ischemia and permanent loss of vision. If this occurs at the level of the optic nerve or more posterior, a complete central retinal artery occlusion can occur. If the blockage occurs along one of the branches of the central retinal artery (CRAO), a branch retinal artery occlusion can occur. Though vision loss may occur with a branch retinal artery occlusion (BRAO), it is much less devastating than a central retinal artery occlusion.

So, what is going on with our patient? On the fundus exam of the right eye, an obvious plaque can be seen along the superior temporal artery. The presence of a plaque is a clear “marker” for possible carotid artery disease or heart disease. Is this what is causing our patient to have amaurosis fugax?

Discussion

Three main types of retinal arterial emboli exist; Hollenhorst plaques, calcific emboli and platelet-fibrin plaques.

Hollenhorst plaques, perhaps the most common, are highly refractile and often glisten when the light from the indirect lens shines on the plaque. Hollenhorst plaques represent cholesterol emboli that originate from atheromatous lesions in the ipsilateral carotid artery or from the aorta. They usually become lodged in the bifurcation of one of the branches of the central retinal artery. In most instances, patients are asymptomatic and are discovered as part of a routine exam.

Calcific plaques are not refractile and have a dull white appearance. They tend to be larger and can be associated with heart valve or aorta calcification.

Platelet-fibrin emboli also dull-white in appearance but are more elongated. They are also associated with carotid artery disease.

The plaque seen in our patient did have a refractile, glisteny appearance, so it is likely a Hollenhorst plaque; however, it is difficult to determine if our patient’s symptoms are a result of the Hollenhorst plaques passing through her retinal circulation. What’s more, even though we only see a single plaque, she had others. Most patients with Hollenhorst plaques are asymptomatic; clearly our patient has symptoms and this deserves serious attention.

Carotid artery disease is one of the major causes of stroke. Stroke itself is one of the most common causes of mortality and severe disability in adults. Patients who have had a stroke will often have preceding ischemic events such as transient ischemic attacks, amaurosis fugax, or both.1,2 For that reason, patients with these symptoms need a full cardiac work up, as well as carotid artery studies such as carotid duplex Doppler ultrasound. Hypercoagulable testing (antiphospholipid antibodies and homocysteine levels) and angiography may be helpful in certain cases.3

Our patient was made aware of our findings and was referred to her primary care physician that same day. We sent her there with a letter explaining our findings and was told that if she was not able to see her primary care physician that day, she should go within the week and that, if she experienced any further symptoms, she should go to the local emergency room.

She was seen one month later for follow up of her symptoms as well as for a glaucoma work-up (IOP, visual fields and OCT). She had not experienced any more amaurosis. She had seen her primary care physician and carotid Doppler studies were performed and were normal. She scheduled an echocardiogram in a few weeks’ time. Her OCT was normal but she did have a corresponding visual field defect in the same area of the Hollenhorst plaque.

She returned two years later, still doing fine and had not had any further symptoms.

1. Hayreh SS, Zimmerman MB. Amaurosis fugax in ocular vascular occlusive disorders: prevalence and pathogeneses. Retina. 2014;34(1):115-22. |