13th Annual Pharmaceuticals ReportCheck out the other feature articles in this month's issue: How—and Why—to Choose Dry Eye Drugs |

The old medical adage of “first, do no harm” is a guiding principle that has steered those in the medical field since ancient times. The simple directive preaches caution in the uncertain world of diagnostics and therapeutics. In optometry, this mindset often makes clinicians pause before they consider using topical steroids. Adverse reactions from steroid use include, but are not limited to, cataract formation, increased intraocular pressure (IOP), possible secondary infections, delayed wound healing and even central serous retinopathy (CSR).1,2 Although these events can be serious and are worth considering, the benefits of steroids often outweigh their risks.

Pros and Cons

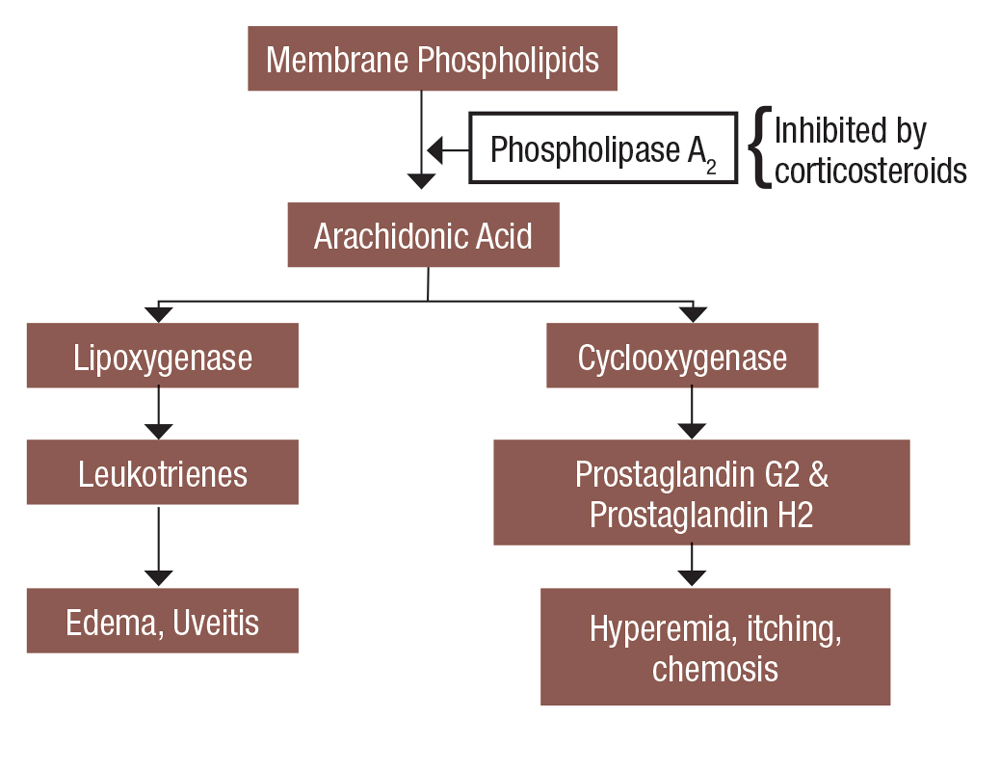

Inflammation is the body’s response to injury or infection, resulting in the release of mast cells, cytokines and other pro-inflammatory mediators.3 Tissue may turn red, become painful or swell during inflammation. In the eye, inflammation may also manifest with injection, blurred vision and photophobia. Ophthalmic corticosteroids, or glucocorticosteroids, are named accordingly because they are similar to the naturally occurring anti-inflammatory hormone, cortisol. They downregulate the inflammatory pathways by inhibiting phospholipase A2.4 Thus, steroids help mediate inflammation by decreasing histamine synthesis, capillary dilation and fibroblast formation (Figure 1).

As with all medications, steroids come with the risk of adverse effects. One of the key concerns many optometrists have when prescribing steroids is their effect on IOP. Up to a third of the population may develop induced ocular hypertension after topical steroid use.5 However, IOP will typically return to pre-treatment levels within three weeks after the cessation of steroid use.6 Posterior subcapsular cataract formation can also be a result of chronic steroid use, both topically and systemically.7

Additionally, steroid use is associated with CSR.8 When this presents, it is imperative that clinicians ask the patient about all of their steroid use, because even over-the-counter topical and inhaled steroids can lead to ocular side effects. Caution must also be used when prescribing steroids with any corneal insult. This is because steroids can suppress the body’s immune response and delay wound healing by downregulating transforming growth factor-β and insulin-like growth factor-I.9,10 On the other hand, because they lower the immune response, steroids are heavily used after corneal grafts to reduce the likelihood of rejection.11

|

Fig. 1. This is a simplified view of how steroids affect the inflammatory cascade. Click image to enlarge. |

Formulation 411

It may seem logical that the incidence and severity of adverse events from steroid use would increase with the strength of the steroid. However, not all steroids are the same, and the medication’s strength is only part of the puzzle. Many steroids are available, each with their own formulation that ultimately affects their potency and the risk of side effects. The specific chemical make-up of each steroid plays a major role in its potential to create an adverse event. Steroid molecules may be attached to acetate, alcohol or phosphate bases—with acetates penetrating an intact cornea the best.12 Additionally, the delivery vehicle also plays a role.

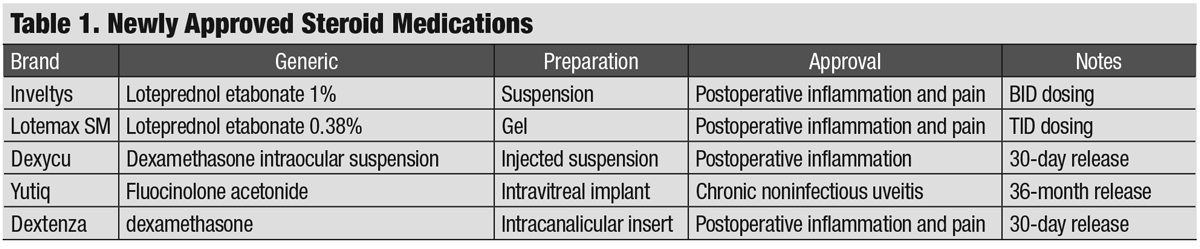

Today’s optometrist not only has to decide on the particular steroid and strength to use, but also if they want a solution, suspension, gel or ointment. Several new options have hit the market in recent years, further complicating the decision (Table 1). Here is a look at the current options and how newer formulations and delivery methods might change your prescribing habits:

Pred Forte (prednisolone acetate ophthalmic suspension 1%, Allergan) has been the workhorse steroid of choice for generations. This product and its generic formulations are suspensions and, therefore, require vigorous shaking prior to instillation. Still, not all suspensions are created equal. A 2007 comparison of branded vs. generic preparations showed that the branded version had smaller and more uniform prednisone particles, which made it more effective in combating ocular inflammation.13 Prednisolone is also available in a phosphate form that is a solution instead of a suspension and therefore does not require vigorous shaking. The phosphate formulation, however, lacks the potency of the acetate form.12

A potent alternative to Pred Forte is Durezol (difluprednate ophthalmic emulsion 0.05%, Novartis). This “designer” steroid adds two fluorine atoms to the prednisone molecule to increase its strength.14 It is approved for the treatment of postoperative pain and inflammation as well as anterior uveitis. Because Durezol is an emulsion, it does not require shaking to deliver an equal amount of active ingredient with each drop. This may be an advantage when treating patients with anterior uveitis who may require dosing every hour with prednisone. Research shows that Durezol four times a day is as good as prednisolone acetate eight times a day; however, it is worth noting that Durezol is more likely to increase IOP than prednisone.15

Topical dexamethasone and fluorometholone, like prednisolone, are corticosteroid suspension eye drops that have been available for years. Both medications are less potent than prednisolone and are considered viable alternatives when clinicians need to mitigate the risks of a stronger steroid.1

|

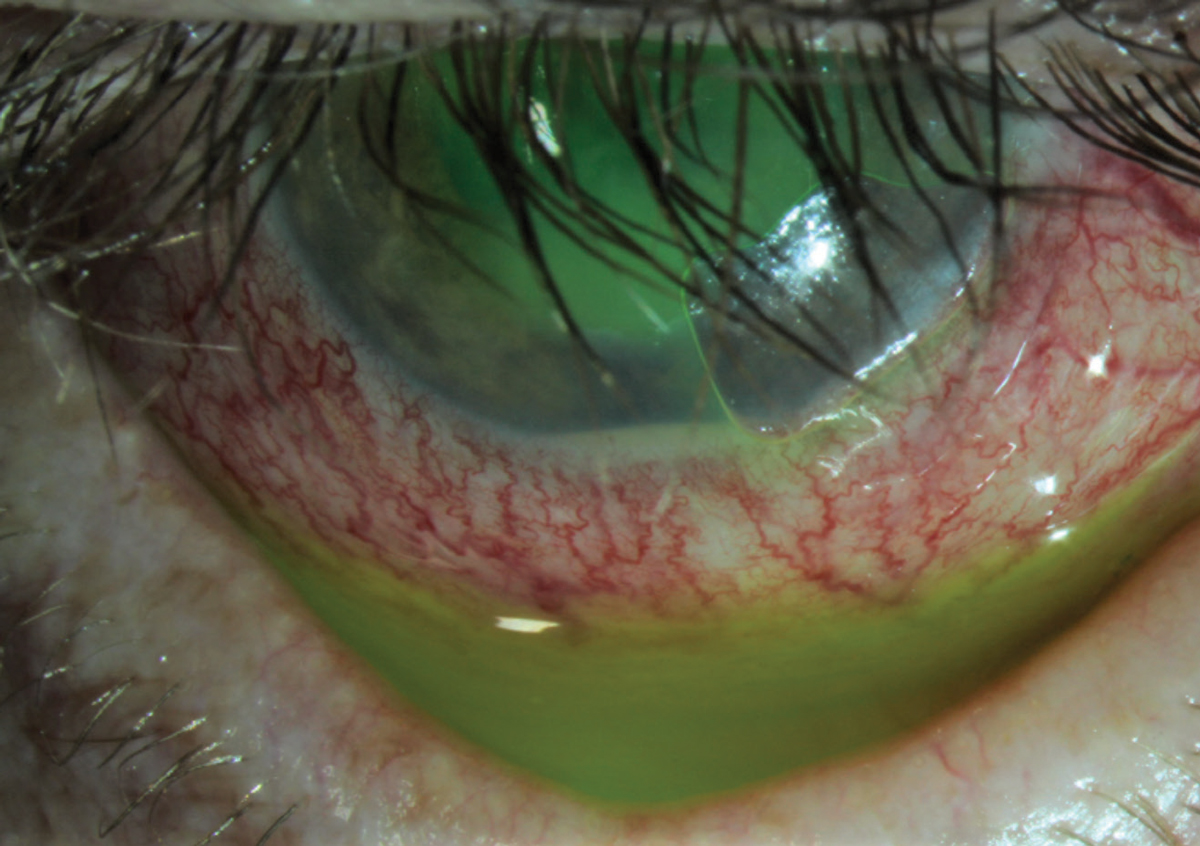

| Fig. 2. This patient presented with a corneal abrasion and hypopyon. He was treated successfully with a bandage contact lens, a topical steroid and a topical antibiotic. Click image to enlarge. |

To further decrease the risk of increased IOP or other events, many optometrists will look to “soft steroids.” These are active compounds that deactivate in a predictable manner during systemic absorption.16 An example of a soft steroid is loteprednol. Two of the oldest and most well-known are Alrex (loteprednol etabonate ophthalmic suspension 0.2%, Bausch + Lomb) and Lotemax (loteprednol etabonate ophthalmic suspension 0.5%, Bausch + Lomb). The weaker of the two, Alrex, is approved for temporary relief of the signs and symptoms of seasonal allergic conjunctivitis.

Lotemax, with more than twice the potency of Alrex, is approved for pain and inflammation after cataract surgery along with other inflammatory conditions such as iritis and allergic conjunctivitis.17 While Lotemax was initially released (and is still available) in a suspension form, it is also available as an ointment and a gel. The ointment is approved for use after multiple ocular surgeries, including LASIK, cataract, minimally invasive glaucoma surgeries and Descemet’s stripping endothelial keratoplasty.17

Two gel formulations exist, Lotemax gel (loteprednol etabonate 0.5%, Bausch + Lomb) and Lotemax SM (loteprednol etabonate 0.38%, Bausch + Lomb). Both have similar indications as the suspension and ointment. One major benefit of the gel formulation is that it ensures a consistent amount of active drug in each drop without the need for shaking.18 Additionally, the gel vehicle remains on the ocular surface longer than a suspension, which helps maximize absorption potential.19

The newest member of the family is Lotemax SM, which uses what the manufacturer calls “submicron technology” to help the medication adhere to the ocular surface. This is designed to improve penetration to the targeted tissues, including presence within the aqueous humor.20,21

With four different Lotemax products to choose from, clinicians have to consider several factors when deciding what to prescribe, including efficacy, availability and affordability. Ointments are great because they don’t require shaking, stay on the eye and can provide some lubrication. However, they can blur vision, and some patients may struggle to instill the proper one-half inch ribbon dose. Lotemax gel and Lotemax SM do not need shaking and may require less dosing, but new products may be more expensive and not as widely available.

In August 2018, Inveltys (loteprednol etabonate ophthalmic suspension 1%, Kala Pharmaceuticals) was approved for postoperative pain and inflammation after ocular surgery. The manufacturer states that Inveltys uses mucus-penetrating nanoparticles to penetrate the ocular surface and reach its target tissue.22 Inveltys is unique among ocular steroids in that it was approved for twice-a-day dosing; other corticosteroids require at least three to four drops a day after surgery.23 This may be particularly useful for patients who require the help of others to instill their medications, have dexterity limitations or have active lifestyles and may be at risk for poor compliance. Postoperative regimens are usually determined by the surgeon, but if you are comanaging cataract surgery, it may be worth your time to discuss this option with your referring surgeon.

|

| Click image to enlarge. |

Dropless Options

Because patient compliance usually increases as the number of medications and dosage decreases, companies have been working to provide steroid options with decreased dosing. To that end, two new medications have been approved that hope to eliminate the need for postoperative steroid drops altogether.

Dexycu (dexamethasone intraocular suspension 9%, EyePoint Pharmaceuticals) is indicated for the treatment of postoperative inflammation. This drug is injected behind the iris and into the posterior chamber after cataract surgery and is slowly released for up to 30 days.

The second drug is Dextenza (dexamethasone ophthalmic insert 0.4mg, Ocular Therapeutix); it delivers a corticosteroid to the eye by way of an intracanalicular insert. Dextenza is a preservative-free insert placed in the lower puncta after surgery. The drug is also slowly released over a 30-day period. Since it is resorbable, there is usually no need to remove it.

The big advantage of these alternative pathways is minimizing patient burden. Fewer drops often equal better compliance and can reduce the amount of preservative on the corneal surface, which could lead to increased patient comfort. Optometrists may also like the dosing control provided by Dextenza and Dexycu. With these medications, there is less worry about the consistency of drug delivery to the target tissue. Side effects can still occur and need to be monitored in the postoperative period.

While not used in optometric practices, injectable steroids are also available. Ozurdex (dexamethasone 0.7mg intravitreal implant, Allergan) is approved for the treatment of macular edema from vein occlusions, diabetic macular edema and for non-infectious uveitis. After insertion, the implant releases 100ug/ml to 1,000ug/ml of the drug for the first two months and then becomes undetectable after seven to eight months.24 The use of intraocular steroids for macular edema seems to be decreasing along with an increased use of anti-VEGF drugs, possibly because of the increased risk of elevated IOP with intraocular dexamamethasone.25

More recently, Yutiq (fluocinolone acetonide 0.18mg intravitreal implant, EyePoint Pharmaceuticals) was approved for chronic noninfectious posterior uveitis. The Yutiq implant delivers a sustained release of drug for up to 36 months. This may be a great alternative to an oral systemic steroid; the local injection eliminates the risks of non-compliance and systemic side effects.26

DO’s and DON’Ts of Steroid UseAlthough steroids provide effective treatment for many ocular conditions, several contraindications exist. Ultimately, the benefit must outweigh the risk. Topical ocular steroids have low systemic absorption, but their side effects can be considerable. Here are a few dos and don’ts when prescribing steroids:1 1. DO hit the inflammation hard and fast. The eye is considered an immune-privileged site, as it can control immune responses to protect the visual system’s delicate components.2 Thus, evidence of inflammation within the eye is uncommon and should be treated promptly to avoid any harmful effects of chronic inflammation. Typically, treatment with a steroid that can penetrate the cornea and treat the anterior chamber inflammation, such as prednisolone acetate or Durezol, is most appropriate. Clinicians should consider dosing every hour to two hours while awake initially. 2. DON’T taper too quickly. Avoiding a fast taper will minimize risk of rebound inflammation. Regarding anterior chamber inflammation, the rule is not to begin your taper until you notice a two-fold improvement in inflammation (based on the Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature criteria).3 However, prolonged use of topical steroids leads to an increased risk of potential adverse effects.4 3. DO refer for potential periocular or intraocular steroid treatment. For intermediate and/or posterior inflammation, cystoid macular edema and recalcitrant cases of uveitis, referral for possible treatment with subtenon’s or intravitreal injections is warranted. 4. DON’T allow refills. One of the added benefits of topical steroids is that they provide almost instant relief of discomfort. However, they are not always safe and appropriate to use, and patients shouldn’t have ongoing access. When another ocular condition presents, patients may be tempted to refill the prescription that made them better previously, but this could be problematic if they have a herpetic, bacterial or fungal infection. 5. DO educate your patient on the formulation. Due to the different ophthalmic formulations, clinicians must educate patients on which steroids require shaking. Patients can easily related to the analogy that a suspension is akin to salad dressing; it requires vigorous shaking to ensure that the medication mixes well before installation—an imperative step for successful treatment. 6. DON’T be afraid to treat the inflammation in a known steroid responder. Because chronic inflammation can cause significant damage to the immune-privileged site of the eye, quelling inflammation even in a steroid responder is necessary. In these patients, start a topical hypotensive agent along with the steroid and continue until the patient is done with the steroid. Additionally, be sure to check intraocular pressure at each visit.

|

Off-label, On Target

The on-label approval for most steroids is for pain after surgery, anterior uveitis or allergy—but there are times when using them off-label may be appropriate (Figure 2):

Dry eye. Clinicians often say that early dry is hard to diagnose and easy to treat, while advanced dry eye is easy to diagnose and hard to treat. Symptomatic patients with chronic inflammation from dry eye disease (DED) can get fast relief with topical steroid drops. The Tear Film and Ocular Surface Society’s Dry Eye Workshop II reported that topical steroids are useful at breaking the cycle of inflammation associated with DED. Also, patients given steroids before or with the initial treatment of cyclosporin did better than patients who were only given cyclosporin.27

Steroid use in DED may be short- or long-term; thus, it may be wise to choose a soft steroid or one that has a lower risk of adverse effects.28 Flarex (fluorometholone, Eyevance Pharmaceuticals) or loteprednol are good choices and are usually dosed two to four times a day, depending on signs and symptoms.

|

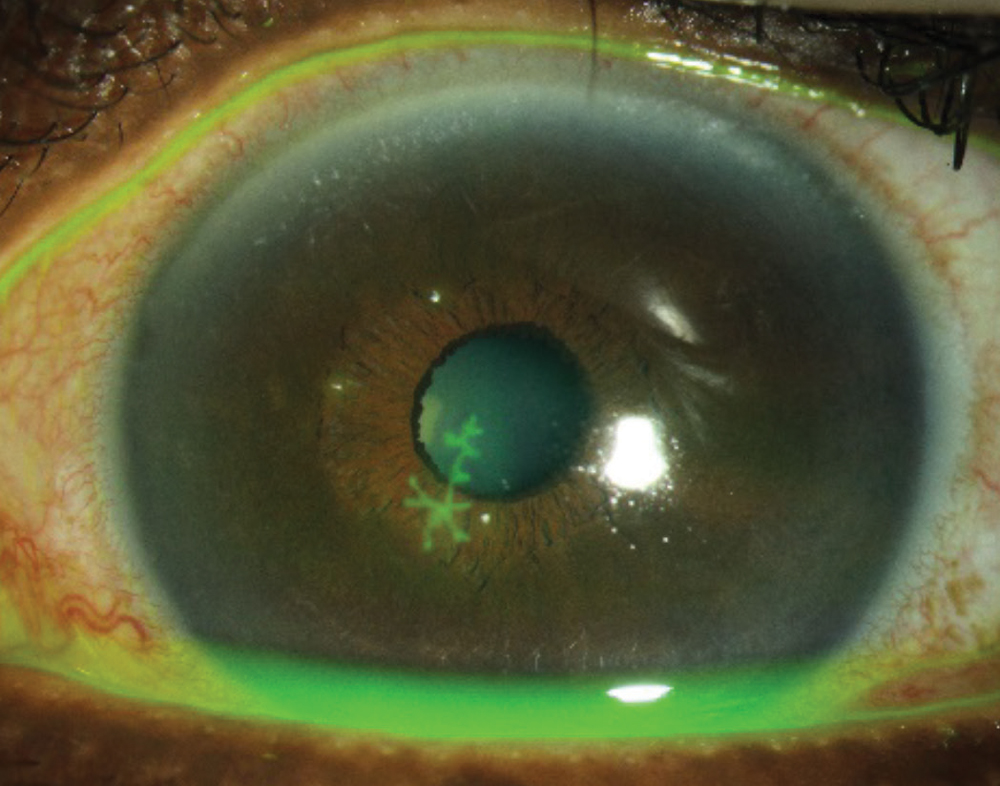

| Fig. 3. Clinicians should avoid prescribing steroids for an epithelial herpetic infection, but they are helpful for cases of stromal herpetic keratitis. Click image to enlarge. |

Corneal ulcers. Many ODs shy away from using topical steroids when the corneal epithelium is not fully intact. This is likely due to the fact the steroids can delay wound healing and have the potential to suppress the immune response, which may lead to an increased risk of infection. However, the Steroids for Corneal Ulcers Trial looked at the use of topical steroids after 48 hours of antibiotics in cases of corneal ulcers and found that long-term vision improve with no safety concerns when steroids were used as an adjunctive therapy for infections not caused by Nocardia.29,30 We have routinely treated non-central corneal ulcers with a combination of steroids and antibiotics with great success. We prefer two-in-one medications such as Tobradex (dexamethasone 0.1%/tobramycin 0.3%, Eyevance Pharmaceuticals) or Zylet (loteprednol 0.5%/tobramycin 0.3%, Bausch + Lomb) over two separate prescriptions. While there is a certain amount of risk with this approach, it can be mitigated with careful patient education and close follow-up.

Herpetic stromal eye disease. Certainly, one of the greatest risks when prescribing steroids is that of herpes simplex keratitis. The classic corneal dendrite is pathognomonic for an epithelial herpetic infection (Figure 3). When dendritic ulcers are present, clinicians should avoid topical steroids, as they may prolong the infection and lead to a larger geographic ulcer. These ulcers can be treated either by topical or oral antiviral medications.

However, in the case of stromal herpetic keratitis without epithelial ulceration, topical steroids should be prescribed at dosages reflective of the amount of inflammation present. This is typically done in conjunction with oral antivirals to reduce the risk of epithelial involvement.31

Steroids are an integral part of optometric practice, and we are fortunate to have many topical options at our disposal. Knowing what makes each drug unique is critical when selecting the best opti for your patient. A strong, deep penetrating steroid may not be needed for mild ocular surface inflammation. Contrarily, a less potent steroid will not get the desired results for severe uveitis. Being aware of the potential adverse effects that may occur when prescribing steroids and how to address them will allow a clinician to treat patients with confidence. In the ever-changing world of pharmaceuticals, the best eye drop for your patient may not be a drop in the near future.

Dr. Sterling practices in Greenville, NC, and is the trustee of administrative affairs for the North Carolina Optometric Society. He is a fellow of both the American Academy of Optometry and the Scleral Lens Education Society.

Dr. DeMarco practices in Kernersville, NC.

Contents in this publication do not represent the view of the US Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government.

| 1. Weiner G. Savvy steroid use. AAO. www.aao.org/eyenet/article/savvy-steroid-use. May 5, 2016. Accessed January 15, 2020. 2. Shah SP, Desai CK, Desai MK, Dikshit RK. Steroid-induced central serous retinopathy. Indian J Pharmacol. 2011;43:607-8. 3. Coutinho AE, Chapman KE. The anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive effects of glucocorticoids, recent developments and mechanistic insights. Molec Cell Endocrinol. 2011;335(1):2-13. 4. Comstock TL, Decory HH. Advances in corticosteroid therapy for ocular inflammation: loteprednol etabonate. Int J Inflam. 2012;2012:789623. 5. Kersey JP, Broadway DC. Corticosteroid-induced glaucoma: a review of the literature. Eye. 2006;20:407-416. 6. LeBlanc RP, Steward RH, Becker B. Coricosteroid provocative testing. Invest Ophthalmol. 1970;9:946-48. 7. Hart WM. Adlers Physiology of the Eye: Clinical Application. St. Louis: Mosby-Year Book; 1992. 8. Chan LY, Adam RS, Adam DN. Localized topical steroid use and central serous retinopathy. J Dermatol Treatment. 2016;27(5):425-426. 9. Petroutsos G, Guimaraes R, Giraud JP, Pouliquen Y. Corticosteroids and corneal epithelial wound healing. Br J Ophthalmol. 1982;66(11):705-08. 10. Wicke C. Effects of steroids and retinoids on wound healing. JAMA Surg. 2000;135(11):1265-70. 11. Kadmiel M, Janoshazi A, Xu X, Cidlowski JA. Glucocorticoid action in human corneal epithelial cells establishes roles for corticosteroids in wound healing and barrier function of the eye. Exp Eye Res. 2016 Nov;152:10-33. 12. Leibowitz H, Kupperman A. Uses of corticosteroids in the treatment of corneal inflammation. In: Leibowitz H, ed. Corneal Disorders: Clinical Diagnosis and Management. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1984:286-307. 13. Roberts CW, Nelson PL. Comparative analysis of prednisolone acetate suspensions. J Ocular Pharmacol Ther. 2007;23(2):182-87. 14. Yamaguchi M, Yasueda S, Isowaki A, et al. Formulation of an ophthalmic lipid emulsion containing an anti-inflammatory steroidal drug, difluprednate. Int J Pharm. 2005;301(1-2):121-8. 15. Sheppard JD, Toyos MM, Kempen JH, et al. Difluprednate 0.05% versus prednisolone acetate 1% for endogenous anterior uveitis: a phase III, multicenter, randomized study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2014;55(5):2993-3002. 16. Howes J. Development of soft drugs for ophthalmic use. In: Ocular Therapeutic and Drug Delivery: A Multidisciplinary Approach. Lancaster: Technomic Publishing;1996;122(2):171-82. 17. Baush + Lomb. Lotemax Ointment (Loteprednol Etabonate) 0.5%. www.lotemaxointment.com. Accessed January 15, 2020. 18. Coffey MJ, Decory HH, Lane SS. Development of non-settling gel formulation of 0.5% loteprednol etabonate for anti-inflammatory use as an ophthalmic drop. Clin Ophthalmol. 2013;7:299-312. 19. Coffey MJ, Decory HH, Lane SS. Development of a non-settling gel formulation of 0.5% loteprednol etabonate for anti-inflammatory use as an ophthalmic drop. Clin Ophthalmol. 2013;7:299-312. 20. Cavet ME, Glogowski S, Lowe ER, Phillips E. Rheological properties, dissolution kinetics, and ocular pharmacokinetics of loteprednol etabonate (submicron) ophthalmic gel 0.38. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2019;35(5):291-300. 21. Fong R, Silverstein BE, Peace JH, et al. Submicron loteprednol etabonate ophthalmic gel 0.38% for the treatment of inflammation and pain after cataract surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2018;44(10):1220-29. 22. Schopf L, Enlow E, Popov A, et al. Ocular pharmacokinetics of a novel loteprednol etabonate 0.4% ophthalmic formulation. Ophthalmol Ther. 2014;3(1-2):63-72. 23. Kim T, Sall K, Holland EJ, et al. Safety and efficacy of twice daily administration of KPI-121 1% for ocular inflammation and pain following cataract surgery. Clin Ophthalmol. 2018 Dec;13:69-86. 24. Poornachandra B, Kumar VBM, Jayadev C, et al. Immortal Ozurdex: A 10-month follow-up of an intralenticular implant. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2017;65(3):255-57. 25. Laine I, Lindholm JM, Ylinen P, Tuuminen R. Intravitreal bevacizumab injections versus dexamethasone implant for treatment-naïve retinal vein occlusion related macular edema. Clin Ophthalmol. 2011 Nov;11:2107-12. 26. Appold K. New product applications: Yutiq implant for chronic noninfectious posterior-segment uveitis. Retinal Physician. April 1, 2019, www.retinalphysician.com/issues/2019/april-2019/new-product-applications-yutiq-implant-for-chroni. Accessed January 15, 2020. 27. Sheppard JD, Donnenfeld ED, Holland EJ, et al. Effect of loteprednol etabonate 0.5% on initiation of dry eye treatment with topical cyclosporine 0.05%. Eye Contact Lens. 2014;40:289-96. 28. Pleyer U, Ursell PG, Rama P. Intraocular pressure effects of common topical steroids for post-cataract inflammation: are they all the same?. Ophthalmol Ther. 2013;2(2):55-72. 29. Srinivasan M, Mascarenhas J, Rajaraman R, et al. The steroids for corneal ulcers trial (SCUT): secondary 12-month clinical outcomes of a randomized controlled trial. Am J Ophthalmol. 2014;157(2):327-333.e3. 30. Srinivasan M, Mascarenhas J, Rajaraman R, et al. Corticosteroids for bacterial keratitis. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012;130(2):143-150. 31. White ML, Chodosh J. Herpes simplex virus keratitis: a treatment guideline - 2014. Am Academy Ophthalmol. www.aao.org/clinical-statement/herpes-simplex-virus-keratitis-treatment-guideline. Accessed January 2020. |