|

Glaucoma is insidious in its slow progression and its virtual absence of symptoms in the early stages. We eye care practitioners bear the burden of detecting this disease and intervening before visual function is compromised.

We routinely perform tonometry and fundus examinations on all patients to screen for glaucoma, regardless of the patient’s age, ocular or medical history. When patients have elevated intraocular pressure (IOP) or apparent cupping of the optic discs, we aggressively initiate additional evaluation of these “glaucoma suspects.” This zeal may seem warranted, given both the disease’s progressive nature and the fact that roughly half of those who suffer from glaucoma are reportedly undiagnosed.1-4 But, glaucoma affects less than 3% of the adult population in the United States, according to epidemiologic studies.1,2 Further, consider a recent report by Fotis Topouzis, MD, PhD. Speaking at the European Glaucoma Society Congress in Prague regarding a clinical investigation of 2,554 subjects 60 years or older, he said, “Only one-third of the patients who had been previously diagnosed with glaucoma had the diagnosis confirmed in the study. The vast majority were undergoing treatment, and a smaller proportion had had laser or surgery.”5 In other words, many so-called glaucoma patients who had been seen and treated did not have the disease at all when evaluated retrospectively. This raises an intriguing question: are we really underdiagnosing glaucoma? Or, could we actually be overdiagnosing the disease?

Case in Point

A 58-year-old black woman presented for a comprehensive evaluation upon referral from her primary care physician. Due to her declining health and complex therapeutic regimen (she was taking approximately 20 medications daily), she had been placed in a skilled nursing facility. She reported a five-year history of glaucoma, for which she was currently using two topical medications (travoprost 0.004% QHS and dorzolamide 2%/timolol maleate 0.5% BID OU) as prescribed by another eye care provider. She had undergone successful cataract extraction in both eyes, approximately one year prior.

|

|

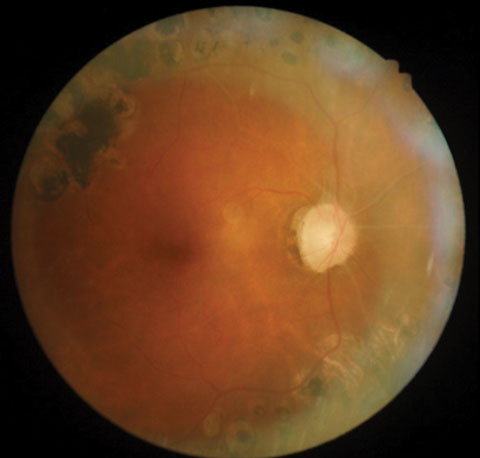

| Posterior pole images from a 58-year-old black female patient. |

Her medical history was positive for Type 2 diabetes, diagnosed at age 23, and treated with insulin. The diabetes had led to proliferative retinopathy for which she’d received panretinal photocoagulation (PRP) in both eyes 10 years earlier. She also had end-stage renal disease, for which she was undergoing kidney dialysis three times a week. A variety of other systemic medications and supplements were prescribed for associated conditions, such as hypertension, coronary artery disease, hypercholesterolemia, Parkinson’s disease, hyperparathyroidism and constipation.

Upon examination, best corrected acuities were 20/40 OD and 20/30 OS. Her visual fields were markedly constricted in both eyes. Extraocular motilities were full, and pupils—while sluggish—reacted bilaterally to light, with no afferent pupillary defect. Examination revealed a healthy anterior segment, with clear media and no evidence of iris neovascularization. IOP was 16mm Hg OD and 17mm Hg OS. Funduscopy revealed extensive scarring of the midperipheral retina in both eyes from prior PRP, and vascular changes consistent with advanced renal disease.

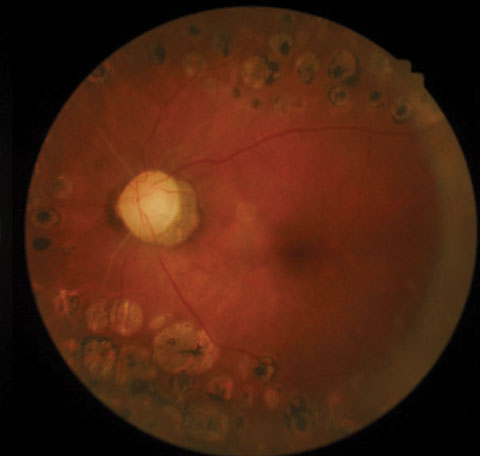

The optic nerves displayed mild pallor (consistent with PRP) and peripapillary atrophy temporally. Moderate, shallow and symmetrical cupping (C/D=0.55) was observed in both eyes, and there was no evidence of disc hemorrhages or retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) defects. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) of the nerves was within normal limits, and aside from a small area of signal loss due to a remnant of fibrotic tissue, the RNFL was intact. Based upon these findings, the patient was instructed to discontinue her glaucoma medications and return in one month for reassessment. At follow-up, IOP was 20mm Hg OD and 21mm Hg OS. Pachymetry measurements revealed central corneal thickness of 530µm OD and 520µm OS. Currently, she is being monitored quarterly, without topical medications.

Where Are We Going Wrong?

There are a number of reasons why practitioners may rush to diagnose glaucoma or incorporate more therapy than is actually required. Unquestionably, the greatest among these is a fear of committing malpractice and subsequently being the target of litigation. Additionally, practitioners may lack the tools and experience necessary to conduct a thorough and accurate assessment of these patients; indeed, some physicians are known to rely solely on tonometry as a basis for their treatment.3 On the other hand, some practitioners may rely too heavily on newer technology, such as OCT or scanning laser polarimetry.6 Using the results of these tests to the exclusion of basic diagnostic considerations (e.g., tonometry, gonioscopy, optic nerve head appearance and visual field assessment) often leads to an erroneous conclusion. Finally, some doctors base their treatment recommendations on the premise that certain glaucoma therapies are prophylactic or “protective” in some way. Unfortunately, without clinical evidence that “neuroprotection” in glaucoma is a reality, this management strategy is likely ill-conceived.7

|

| OCT readings from the same patient. Click image to enlarge. |

The Harm in Overdiagnosis

One certainly could make the argument that it’s safer—from a clinical/legal perspective at least—to initiate IOP-lowering therapy for all those who demonstrate glaucomatous risk factors. Certainly, no ethical practitioner would care to see a patient lose vision from a manageable disorder. However, the implications of overdiagnosis and overtreatment are substantial and must also be considered. A major concern is the growing economic burden of glaucoma therapy, which amounts to roughly $5.8 billion annually.8 If 50% (or more) of these patients don’t actually require medical intervention, the cost savings to our patients and third party payers is substantial.3,9 Additionally, one must weigh the impact on quality of life in terms of obtaining and using medications. Topical IOP-lowering agents, even those requiring just once or twice daily administration, can be inconvenient to use and complicate the patient’s overall drug regimen. Finally, any medical or surgical therapy may predispose toward additional risks and side effects, which must be borne by the patient; if glaucoma is truly not present, then these risks are borne needlessly.

We recommend patience and diligence in making a glaucoma diagnosis or amplifying therapy. Experts agree not all suspects require immediate treatment.10 As easy as it may be to write an initial prescription for latanoprost or brimonidine, we need always be certain that such therapy is actually in the patient’s best interest. Likewise, when a patient is new to the office and offers a history of glaucoma that was treated by another physician, we must maintain a healthy degree of skepticism. Always verify that the diagnosis and that the current treatment strategy is appropriate. Stopping medications for two to four weeks is perfectly acceptable in cases that may seem unusual or questionable.

In the end, remember that glaucoma is not a disease of days and weeks, but rather of months and years. With rare exceptions, we can well afford the extra time it takes to be competent, caring and compassionate providers.

|

1. Friedman D, Wolfs R, O’Colmain B, et al. Eye Diseases Prevalence Research Group. Prevalence of open-angle glaucoma among adults in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol. 2004 Apr;122(4):532-8. 2. Topouzis F, Coleman AL, Harris A, et al. Factors associated with undiagnosed open-angle glaucoma: the Thessaloniki Eye Study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008 Feb;145(2):327-35. 3. Nayak BK, Maskati QB, Parikh R. The unique problem of glaucoma: under-diagnosis and over-treatment. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2011 Jan;59 Suppl:S1-2. 4. Klein R, Klein BE. The prevalence of age-related eye diseases and visual impairment in aging: current estimates. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013 Dec 13;54(14):ORSF5-ORSF13. 5. Topouzis F. Undiagnosed glaucoma vs. over-diagnosis. Presented at: European Glaucoma Society Congress; June 19-22, 2016; Prague. 6. Garway-Heath DF, Friedman DS. How should results from clinical tests be integrated into the diagnostic process? Ophthalmology. 2006 Sep;113(9):1479-80. 7. Doozandeh A, Yazdani S. Neuroprotection in glaucoma. J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2016 Apr-Jun;11(2):209-20. 8. Wittenborn J, Rein D. Cost of vision problems: The economic burden of vision loss and eye disorders in the United States. Prevent Blindness America. June 11, 2013. Accessed: July 21, 2016. www.preventblindness.org/sites/default/files/national/documents/Economic%20Burden%20of%20Vision%20Final%20Report_130611.pdf. 9. Vaahtoranta-Lehtonen H, Tuulonen A, Aronen P, et al. Cost effectiveness and cost utility of an organized screening programme for glaucoma. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2007 Aug;85(5):508-18. 10. Appropriateness of Treating Glaucoma Suspects RAND Study Group. For which glaucoma suspects is it appropriate to initiate treatment? Ophthalmology. 2009 Apr;116(4):710-6. |