|

History

A 26-year-old Caucasian female presented for an eye examination without any chief complaints. She had not had an eye evaluation in more than five years and wanted to update her medical status.

She reported no history of ocular disease or systemic illnesses of any kind. She also denied having allergies of any kind.

Diagnostic Data

Her best-corrected visual acuity was measured at 20/20 OU. An external examination was deemed to be normal and no evidence of afferent pupillary defect was seen.

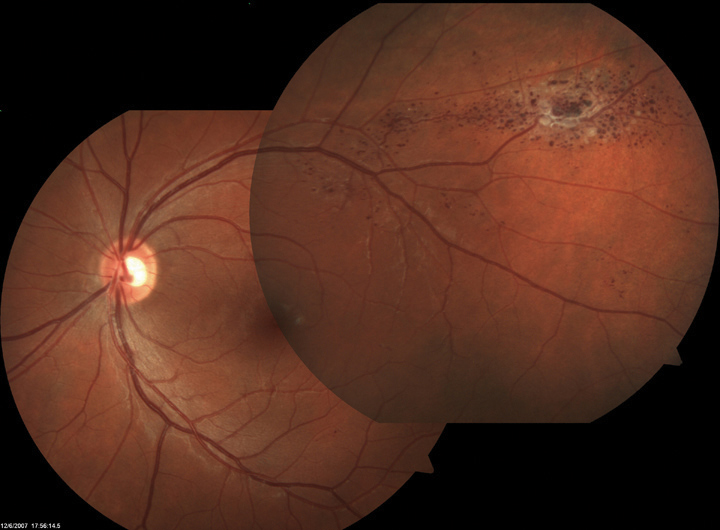

A refractive evaluation, however, uncovered that she had a mild hyperopia of +0.50D. Biomicroscopy revealed normal lids and lashes in both eyes with normal, healthy anterior segment structures. The intraocular pressures for both of her eyes was measured at 16mm Hg with the use of Goldmann applanation. The pertinent posterior segment finding is documented in the fundus photographs provided.

Your Diagnosis

Does the patient’s case presented require any additional tests, history or information? What steps would you take to manage this patient? Based on the information provided, what diagnosis would you make? What is the patient’s most likely prognosis?

|

| The findings in these fundus photographs portray a 26-year-old patient who presented without any complaint. Does the imaging provide insight into any signs of ocular disease? |

Additional testing

Additional testing might include fundus photography, optical coherence tomography, fluorescein angiography and magetic resonance imaging (MRI) to rule out similar lesions inside the head.

The diagnosis in this issue is cavernous hemangioma of the retina (CHR). Cavernous hemangioma of the retina and or optic disc are rare lesions. First noted in 1971, they are deserving of their own classification as unique entity.1-3 Universally benign, they represent asymptomatic, congenital malformations of the retinal blood vasculature that are non-progressive, usually unilateral, with a propensity for increased frequency in women.4 Since they produce no dysfunction unless they occur in the macula (producing decreased acuity) or bleed (produce the symptom of floating spots), they often remain undiscovered until they are observed via fundoscopy. They are rarely a source of intraocular hemorrhage.1-4 When they do produce spontaneous vitreous bleeding, without treatment the episodes are often recurrent and significant.3

CHR are easily recognized by their characteristic saccular "grape-like" appearance.1,3,4 While the tumors are generally considered to be static and not capable of growth, the literature documents two cases of cavernous hemangioma of the optic nerve which demonstrated an increase in size.1 The fluorescein angiographic features include a normal arterial and venous supply, extraordinarily slowed venous drainage, no arterio-venous shunting, no disturbances of vascular permeability, no secondary retinal exudation and the unique formation of isolated clusters of vascular globules with plasma/erythrocyte sedimentation surrounding the main body of the malformation.4

Cavernous hemangioma of the retina, optic nerve or choroid may serve as the ocular component of the neuro-oculo-cutaneous phacomatosis sometimes referred to as cavernoma multiplex.5 The literature has documented a case in which a cavernous hemangioma interfered with oculomotor nerve function causing oculomotor disturbances, ptosis and visual impairment via a compressive etiology.6

Cavernous hemangioma of the retina is considered a hamartoma (from the Greek meaning a benign overgrowth of mature cells normally found in the affected area). Typically they have an autosomal dominant inheritance pattrern.2,7,8 They affect both sexes equally and can be seen in all ethnicities.3 Most individuals have a single lesion (consisting of multiple saccular components) in one eye with no other ocular or systemic anomalies.3 However, on occasion the disturbance can be found demonstrating multiple lesions in one retina along with abnormal vascular lesions of the skin and central nervous system (CNS).3 The lesions themselves consist of clustered, large, thin-walled, intraretinal vessels lined with normal, healthy, vascular endothelium, that have taken the shape of round saccules.3 As the tumor evolves it displaces and replaces the sensory retina in that zone.3 There is no recognized malignant potential.1-7

These lesions rarely require therapeutic intervention over the lifetime of the patient.1-7 They do necessitate any restriction of activity and typically remain stable and unchanged over the course of time. However, because of their vascular nature and their potential to serve as markers for alternate locations, there is always some risk of other lesions in the head.1-7 Unfortunately, these unusual formations may also exist in the brain.6 While rare, the possibility of intracranial hemorrhage must be viewed as a life threatening sequellae.6 For these reasons individuals with cavernous hemangioma of the retina should be referred for neuroimaging.2-7 Advice should be offered to family members, with or without fundus findings, to also seek neuroimaging so that absence of the malformation can be confirmed or so that neurosurgical prophylactic treatment can be advised.2,7

When these lesions interfere with functioning either by impingement via growth or by exudation, shrinkage and or closure can be attempted with photodynamic therapy.9-11 Verteporfin-based photodynamic therapy has been demonstrated to exhibit some success in achieving closure of large retinal capillary hemangiomas.8-11 When performed using the appropriate technique, the hemangiomata exposed to the treatment either shrunk in size or underwent complete closure with resultant mitigation of excessive exudation and the creation of overlying fibrosis.9-11 Unfortunately, a side effect of the process is potential tractional macular puckering.9 In most instances the treatment successfully improved the visual acuity.9-11

Cavernous hemangioma of the retina are considered to stable intraretinal lesions. The same tumor seen on the optic disc has the potential for growth, causing vitreous hemorrhage and therefore should be closely monitored. The presence of either retinal cavernous hemangioma or choroidal hemangioma should alert the clinician to search for features suggestive of systemic and familial involvement. The principle differential diagnoses include exudative retinal telagiectasis and Coat’s disease, the vascular Von Hipple Lindau tumor and the arteriovenous malformation (Racemose hemangioma/Wyburn Mason syndrome).

This patient also had a slightly enlarged cup/disc ratio. The patient was scheduled for fundus photography of the nerves to document the discs and also fundus photography of the CHR. The low risk (no Drance hemorrhage, no disc notch, no nerve fiber layer drop out, young age, normal intraocular pressure, no family history of glaucoma, no evidence of migraine headache) of glaucoma made further baseline studies optional at a later time. The patient was referred to a retinologist for definitive diagnosis and to rule out the need for fluorescein angiography and to rule out the need for neuroimaging. The retinologist agreed with the diagnosis and obtained and and MRI of the head (which was negative). The patient was educated and scheduled for biannual follow up evaluations without restrictions or limitations on activity.

1. Kushner MS, Jampol LM, Haller JA. Cavernous hemangioma of the optic nerve. Retina. 1994;14(4):359-61. |