|

|

|

I recently examined two new patients: one was referred for a diabetic retinal examination and the other to establish care. Each was referred by separate primary care providers. The patients’ presentations seemed similar at first glance. But, first impressions can be misleading.

Diagnostic Data

The first patient, Alice, is a 59-year-old white female diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes mellitus, for which she was recently prescribed metformin to help drive down her rising glucose levels. She was also on Zyrtec (cetirizine, McNeil), low-dose (81mg) aspirin QD, Aciphex (rabeprazole, Eisai) and Synthroid (levothyroxine, AbbVie).

The second patient, Barry, is a 64-year-old white male who hadn’t had an eye exam in several years, but was nudged to do so by his family doctor. He was taking lisinopril, amlodipine and Crestor.

Alice was a low myope with best-corrected visual acuity of 20/20-1 OD and OS. Barry too was a myope and also best corrected to 20/20-1 OD and OS. Pupils were normal in each patient and their extraocular motilities were full in all positions of gaze.

|

|

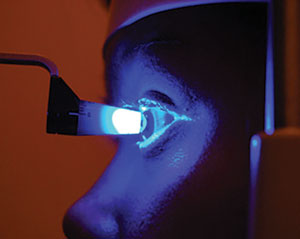

| Both patients presented at their initial visits with uncontrolled glaucoma, with intraocular pressures measured in the 30s. Do you begin topical drops that day, or do you need more information first? Photo: Mark M. Cheung, OD |

Anterior chamber angles in each patient were open, as estimated by the Van Herick method. Alice’s intraocular pressures measured 32mm Hg OD and 34mm Hg OS at 3:15pm. Barry’s IOP measured 33mm Hg OD and 38mm Hg OS at 3:55pm. Corneal thicknesses for Alice measured 542µm OD and 556µm OS, while Barry’s were 560µm OD and 558µm OS.

Upon dilation, each had early nuclear sclerotic lens changes that correlated with their best-corrected visual acuities; Barry also had a few cortical spokes not encroaching on the visual axis. Each patient had posterior vitreous detachments OU.

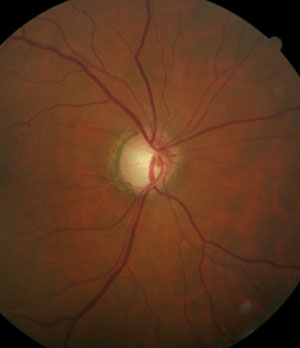

Alice had normal-sized optic nerves, with cup-to-disc ratios of 0.50 x 0.65 OD and 0.60 x 0.65 OS, with a somewhat thinned neuroretinal rim inferotemporally. Barry also had normal-sized optic nerves, with cup-to-disc ratios of 0.55 x 0.70 OD and 0.60 x 0.75 OS, also with neuroretinal rims that do not follow the ISNT rule.

We obtained Heidelberg Retina Tomograph-3 (HRT-3, Heidelberg Engineering) imaging of the optic nerves at the initial visits, which corroborated the described cup-to-disc ratios and thinned neuroretinal rims.

Retinal vascular examination of each patient was similar in that mild arteriolar sclerotic retinopathy was present in both eyes. Alice’s macular evaluation was unremarkable except for mild retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) granulation consistent with her age, whereas Barry had some fine RPE mottling OU with some drusen in the temporal foveal avascular zone (OD>OS). Peripheral retinal evaluations in each patient were unremarkable.

Diagnosis

At each patient’s initial visit, I diagnosed uncontrolled glaucoma.

The question now: What is the very next step for these two patients? Should they begin medication right away, or await further testing?

Discussion

Clearly, both patients have glaucoma and need intervention to prevent further damage. However, it’s not feasible to perform all necessary baseline testing during the initial work-up, so we scheduled both patients for follow-up visits to obtain the remaining information.

Now, why not just medicate these patients at the conclusion of their initial visits? After all, the patients will be on medications anyway. And with IOPs as elevated as they are, shouldn’t the patients be medicated now to help stave off further damage?

The answer to those questions boils down to your level of suspicion for imminent damage during that next week or two until the follow-up visit.

Progression can occur rapidly in open-angle glaucoma patients, typically when high IOP coincides with a frail neuroretinal rim, in the “perfect storm” of risk.

Certainly, in the presence of advanced disease (and these patients have moderate to moderately advanced disease already) with a frail, thin neuroretinal rim that is clearly showing advanced damage, therapy at the conclusion of the initial visit is warranted.

The same holds true for significantly elevated IOP (and the argument can be made here that each patient’s IOP is significantly elevated already) that puts the patient not only at risk for further nerve damage but also retinal vein occlusion or ischemia in the presence of poor ocular perfusion. Again, initiate therapy at that visit.

But, in cases such as these—involving open angles and no evidence of angle closure—keep in mind that glaucoma is chronic in nature.

Build a Better Baseline

There is another important aspect to consider for patients who are going to be chronically medicated: establishment of a baseline untreated IOP, upon which the efficacy of all future therapy is based.

|

|

|

|

|

Patients diagnosed with open-angle glaucoma will be medicated for the rest of their lives. Make sure you have a good handle on the baseline IOP so you fully understand the therapeutic effect. |

For each of these patients, we have only one set of IOP readings so far. Now, here’s where the two cases diverge—and it highlights the need to assess pre-treatment IOP. In both cases, though IOPs were high and damage existed, I chose not to medicate on the first visit, and instead will initiate therapy after their follow-up visits. Why wait to medicate? Because one IOP reading generally doesn’t tell us enough—and it’s simply not prudent to treat glaucoma, or almost any disease, without having a good clinical assessment of the starting point.

So, their follow-up visits certainly included a second IOP measurement as well as those other remaining pieces to the glaucoma puzzle—threshold visual fields, gonioscopy, stereo photography, optical coherence tomography of the retinal nerve fiber and ganglion cell layers, and ultrasound biomicroscopy.

In both patients, results of follow-up testing were consistent with open-angle glaucoma, with good correlation between structure and function.

But the take-home lesson is in each patient’s second IOP readings. Alice’s IOPs measured 25mm Hg OD and 26mm Hg OS, while Barry had IOPs of 33mm Hg OD and 37mm Hg OS. Obviously, Alice had a larger variation from the initial readings, whereas Barry’s IOPs were about identical to his original pressures.

This, in turn, plays a big role in what we would consider our starting point of unmedicated IOP. Barry’s case is straightforward: unmedicated IOPs were in the low 30s OD and mid-30s OS. Alice, on the other hand, had pre-medicated IOPs of upper 20s to low 30s OU—a broader range correlating with the variances in IOP.

At the end of each of their second visits, I prescribed Zioptan (tafluprost 0.0015%, Akorn) HS OU. I’ve seen each patient twice since that visit; Alice has average medicated IOPs of 24mm Hg OD and OS. Barry has average medicated IOPs of 23mm Hg OD and OS.

Both patients are experiencing a reduction in IOP on medication, but are they (relatively) equally controlled? I think Barry, at this point, is more stabilized than Alice, simply because he has had a 40% reduction in IOP from a relatively stable baseline. Alice, on the other hand, may be stabilized, but I can make the argument that she might not be fully stabilized. Because Alice had a greater variation from baseline to medicated, it hints that she might still fluctuate. Only time will tell.

So, these two patients, with similar initial findings and similar responses to medical therapy, differ in my assessment and certainty of stability at this early stage of therapy—all because of the second IOP measurement for each patient. Had I not obtained that second pretreatment IOP for each patient, the therapeutic effect and assessment of stability may well have been considered equal.

Therefore, in the large majority of recently diagnosed glaucoma patients, obtain several pre-treatment IOP measurements to better assess a baseline. Remember, that baseline is the essential metric upon which all future therapy is judged, so get as accurate a measurement as possible.