|

One of the biggest challenges in ocular surface disease is that the term itself is a misnomer: in very many cases, although the effects manifest on the ocular surface, the disease process takes place on the eyelids. So, when managing dry eye, it is imperative that you begin your clinical and diagnostic assessment with the eyelids and the problems that can occur there.

This concept was first emphasized in the International Task Force’s Dysfunctional Tear Syndrome Delphi Approach Report, and most recently as a primary recommendation from the Dry Eye Summit held in Dallas-Fort Worth this past December.1 It helps you realize the part blepharitis plays in dry eye disease—whether it’s anterior blepharitis affecting the eyelashes and eyelids or the posterior blepharitis at work in meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD). Blepharitis affects all ages and all ethnic groups; in one survey ophthalmologists and optometrists reported that 37% to 47% of all patients they saw had blepharitis.2

Not All Blepharitis Cases are the Same

I started my first dry eye clinic almost 20 years ago, and I have to admit that in the early days I treated all blepharitis as if it were the same. Not only did I fail to differentiate between the types of anterior blepharitis, at the time I truly didn’t know to look for posterior blepharitis or MGD. No wonder I struggled for so many years in managing these patients, despite my practice’s focus on dry eye disease management.

Fortunately, newer research has paved the way for a better understanding of the disease. That, combined with chronic clinical defeat or frustration, forces you to solve these problems and uncover insights worth implementing in clinical practice. One of those insights is to diagnose not simply “anterior blepharitis” but also the type of anterior blepharitis, and then customize your treatments accordingly.

Blepharitis is simply defined as inflammation of the eyelids. Because of this overly broad definition, many forms of lid disease qualify as “blepharitis,” including some—such as periorbital eczema in cases of atopic keratoconjunctivitis—that we wouldn’t normally feel inclined to define that way. Below, we’ll focus on three common anterior blepharitis types and discuss their key symptoms, signs and treatment options.

Staphylococcal Blepharitis

The organisms Staphylococcus epidermis and Staphylococcus aureus are ubiquitous on the human body. For multifactorial reasons, certain patients develop an overabundance of these bacteria, leading to complaints that typically include:

| |

| The debris on these eyelashes indicates Staphylococcal blepharitis. |

• mattering/crusting

• debris on the lashes

• irritated or swollen eyelids and eyelash margins

• hordeola development

• eyelid ulceration, in severe cases

• potential conjunctival involvement

The classic appearance of Staph. blepharitis is described as yellowish debris or collaretes, matter or discharge and erythema and hyperemia of the eyelid margins.3 This condition can lead to damage of the eyelid margins, including ductal metaplasia, tear film instability and even primary and postsurgical infections.

Treatment for Staph. blepharitis should include eyelid hygiene involving commercial foam surfactant cleansers, warm compresses and hypochlorous acid-based cleansers for more severe forms. Topical antibiotics are effective in acute cases where the bacterial component is the primary cause.4 In chronic cases, the condition becomes more inflammatory, and combination agents (antibiotic/steroid drops and ointments) seem to work well in treating the infection and inflammation.5,6 You can also provide in-office mechanical treatments to reduce the bacterial colonization to a proper level.

Long-term maintenance is best achieved with patient education about the chronic nature of the disease and that there is no known cure, along with routine use of commercial eyelid cleansers.7

Demodex Blepharitis

The eyelid mites Demodex brevis and Demodex folliculorum become more prevalent as we age, and studies have shown that the majority of blepharitis cases in patients above age 60 are caused by Demodex.8 Patients with rosacea are much more likely to experience Demodex blepharitis as well. The average healthy person has over 2,000 Demodex mites on their body at any given time.9 Overabundance results in a presentation of clear ‘sleeves’ and debris that appear to be focused primarily at the base of the lashes.

| |

| Collarettes around the base of the lashes is a sign this blepharitis is caused by Demodex. |

The most common complaint of patients is itching of the lid margins and, in longstanding cases, madarosis or loss of lashes. Perhaps the most common way that it has traditionally been diagnosed is as a last resort, when the presentation is unresponsive to other treatments.10 As clinicians, we should raise our level of suspicion and awareness in at-risk patients rather than allowing it to be a diagnosis of exclusion.

Treatment requires the use of tea tree oil, and most effective treatments are usually approaching a concentration of 50%. Formulations above 50% are often too strong for the ocular surface and can be uncomfortable to the patient. There are a number of commercial in-office ‘kits’ available to treat this form of blepharitis and appear to be superior or at least less uncomfortable than creating a 50% tea tree oil solution on your own.

High concentrations or impurities in tea tree oil can be uncomfortable for patients, so companies have found novel ways to minimize that concentration or the toxins that could be present. The Ocusoft Demodex kit adds buckthorn seed oil to the tea tree oil, as both ingredients have been shown to be effective against Demodex mites. Cliradex (BioTissue) isolates the active ingredient in tea tree oil, known as 4-terpineol, in its Cliradex Complete kits, thus avoiding many of the potential toxins that could be present in commercial tea tree solutions.

In addition to the tea tree oil, these kits often contain a double-sided brush—one side for applying the solution and the other side for scrubbing the lid margins. You could also use a mechanical in-office cleaner. This treatment should be performed after applying topical anesthetic to the upper eyelid margins. Wait three to five minutes and then repeat the anesthetic and treatment. Most patients require multiple treatments and should be advised to use the other products in the kits at home each night. Patients will typically mention burning or tingling during or after the procedure. Be sure that during treatment, patients keep their eyes closed at all times to avoid corneal abrasion.

This form of blepharitis is chronic, and patients must expect it to return, but hopefully not for months or years. Maintenance may help and can involve Cliradex pads periodically or commercial cleansers such as Oust Demodex Cleanser (Ocusoft) or SteriLid (TheraTears) that have a small amount of tea tree oil present, not likely sufficient for a primary treatment but perhaps for maintenance after the in-office treatments used on a consistent daily basis.

Seborrheic Blepharitis

A third form of blepharitis is the dematologic condition known as seborrheic blepharitis. This is often described as oily or greasy eyelid deposits, mild conjunctival injection and inferior punctate epithelial erosions; however, it rarely produces any effects on the eyelashes.11 Patients with this form of blepharitis will often present with complaints that focus on the eyelids themselves, including irritation, redness and occasionally itching.

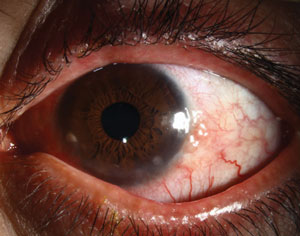

| |

| It’s also common for patients to have both anterior and posterior blepharitis simultaneously, as seen here. Photo: Christine Sindt, OD |

This condition is best treated with a topical corticosteroid such as triamcinolone cream 0.1% or, if you are concerned about the patient getting the product in the eyes, an ophthalmic steroid such as Lotemax (loteprednol, Bausch + Lomb) or fluorometholone ointment (FML, Allergan). Patients should use corticosteroids on the eyelids for no more than two to three weeks. Fluorinated steroids, for example, have been shown to cause eyelid thinning or discoloration with long-term use.12

This form of blepharitis is also chronic and will return. Patients may be able to keep it maintained with daily use of commercial lid scrub surfactant cleansers.

Each of these forms of blepharitis has a different presentation, and each also has a different approach to treatment. Maintenance therapies (lid hygiene) are similar among the subgroups, yet various options exist depending on presentation and severity. Finally, it is important for patients to understand that blepharitis, like arthritis, is a condition that cannot currently be cured.13 But like arthritis, if under the good care of a doctor and with steady compliance, patients can go months or years with few symptoms. Understanding the types of anterior blepharitis in presentation and treatment will better help you manage this common ocular surface disease that affects millions of patients.

1. Behrens A, Doyle, JJ, Stern L, et al. Dysfunctional tear syndrome: a delphi approach to treatment recommendations. Cornea. 2006;25:900–7.2. Lemp MA, Nichols KK. Blepharitis in the United States 2009: a survey- based perspective on prevalence and treatment. Ocul Surf. 2009;7(2 suppl):S1-14.

3. Oto S, Aydin P, Ciftcioglu N, Durson D. Slime production by coagulase-negative staphylococci isolated in chronic blepharitis. Eur J Ophthalmol. 1998;8:1-3.

4. Yactayo-Miranda Y, Ta CN, He L, et al. A prospective study determining the efficacy of topical 0.5% levofloxacin on bacterial flora of patients with chronic blepharoconjunctivitis. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2009;247:993-8.

5. Chen M, Gong L, Sun X, et al. A multicenter, randomized, parallel-group, clinical trial comparing the safety and efficacy of loteprednol etabonate 0.5%/tobramycin 0.3% with dexamethasone 0.1%/tobramycin 0.3% in the treatment of Chinese patients with blepharokeratoconjunctivitis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2012;28:385-94.

6. White EM, Macy JI, Bateman KM, Comstock TL. Comparison of the safety and efficacy of loteprednol 0.5%/tobramycin 0.3% with dexamethasone 0.1%/tobramycin 0.3% in the treatment of blepharokeratoconjunctivitis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24:287-96.

7. Lindsley K, Matsumura S, Hatef E, Akpek EK. Interventions for chronic blepharitis (review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;16:5.

8. Zhao YE, Wu LP, Hu L, Xu JR. Association of blepharitis with Demodex: a meta-analysis. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2012;19:95-102.

9. Szkaradkiewicz A, Chudzicka-Strugala I, Karpinski TM, et al. Bacillus oleronius and Demodex mite infestation in patients with chronic blepharitis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:1020-5.

10. Zhao YE, Wu LP, Hu L, Xu JR. Association of blepharitis with Demodex: a meta-analysis. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2012;19:95-102.

11. Pflugfelder SC, Karpecki PM, Perez VL. Treatment of blepharitis: recent clinical trials. The Ocular Surface. 2014 October;12(4).

12. Shlivko IL, Kamensky VA, Donchenko EV, Agrba P. Morphological changes in skin of different phototypes under the action of topical corticosteroid therapy and tacrolimus. Skin Res Technol. 2014 May;20(2):136-40.

13. Lindsley K, Matsumura S, Hatef E, Akpek EK. Interventions for chronic blepharitis (review). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;16:5.