|

JadeE S. Schiffman, M.D.; Rosa A. Tang, M.D.; and Sonali Singh, M.D. |

A 36-year-old white female presented, complaining of constant periorbital headaches on the right side, accompanied by ptosis and miotic pupil.

Some four weeks earlier the patient developed a temporal scintillating scotoma in her right eye; this lasted 15-30 minutes. An acute, painful headache, also on the right side, followed. Hours later, this became a constant, dull 3/10 periorbital muscle ache. The constant daily headaches were not associated with nausea, vomiting, lacrimation, conjunctival redness or photophobia. Though she initially denied any precipitating event, the patient then recalled that on that day, prior to her photopsia, she made a forceful head, neck and body turn to the left to prevent her baby from falling.

Five days after that event, she experienced a flickering fortification spectrum. She took Imitrex (sumatriptan), but the headache did not subside. In fact, it got worse. She later took ibuprofen, which decreased the intensity.

|

| A positive Paredrine test in which the right pupil did not dilate to 5%, indicating a postganglionic Horners syndrome. |

Nine days later, the patient noticed that her right pupil appeared smaller, and that her right upper lid was ptotic. She denied anhydrosis, facial redness, and arm or hand pain. She did note that the right portion of her face felt congested.

A day later10 days after the initial eventthe patient saw her physician, who treated her for a sinus headache with a decongestant. Still, she experienced no relief. A week later, a neurologist diagnosed her with a partial right Horners syndrome, but no pharmacological testing or neuroimaging was done.

There was no history of surgery, chiropractic manipulation, iris heterochromia or change in facial sensation. She denied any vision loss, blurred vision or diplopia.

The patients medical history was unremarkable. She was taking ibuprofen and had no known drug allergies. Her family medical history was positive for migraines.

Diagnostic Data

Best-corrected visual acuity was 20/20 O.U. at distance and near. In light, the pupils measured 3.5mm O.D. and 4mm O.S. The anisocoria was greater in the dark, with the pupils measuring 4mm O.D. and 6.5mm O.S. A dilation lag was present in the right eye.

The motility exam was normal. Paredrine (hydroxyamphetamine) testing was positive for Horners syndrome O.D. There was a slight right lid ptosis, and margin to reflex distance was 2mm on the right and 2.5mm on the left. The orbital structures appeared unremarkable. All other findings were unremarkable.

Diagnosis

We diagnosed a post-ganglionic right Horners syndrome with concurrent headache and scintillating scotomas. We suspected that the Horners was secondary to a right internal carotid artery dissection.

|

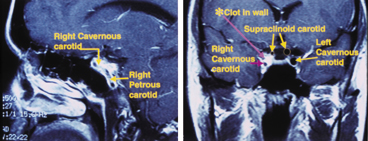

| Sagittal MRI (left) shows the ICAD in the wall of the petrous and cavernous sinus segments. Coronal MRI (right) shows significant narrowing of the carotid lumen in the cavernous sinus and supraclinoid segments of the right ICA. |

Treatment and Follow-up

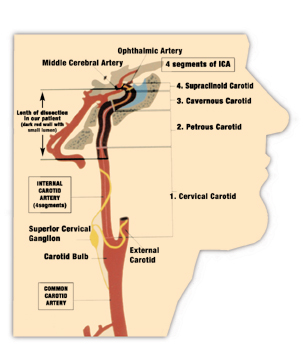

Emergency MRI and MRA of the head and neck showed an extensive right carotid artery dissection that started in the cervical portion of the carotid (extracranial) artery. It extended through the petrous, intracranial (cavernous sinus) and supraclinoid portions, and to the right middle cerebral artery.

A large subintimal hemorrhage and an intramural thrombus, both of which are life-threatening, were present. There was severe narrowing at the petrous and cavernous portion of the internal carotid artery (ICA), but not total occlusion.

The patient was hospitalized immediately due to the risk of acute stroke, and placed on heparin anticoagulation therapy. She was then placed on Coumadin (warfarin) for six months and followed by the neurology department. The patient is now symptom-free and is expected to be taken off Coumadin.

Discussion

Carotid artery dissection (CAD) causes ischemic stroke in 2% of the general population, but accounts for 10-25% of ischemic strokes in the young to middle-aged population.1 Though no predilection for sex has been documented, the condition may be more common in women.2

Dissections of the carotid artery result when blood penetrates through a tear in the inner arterial wall and accumulates within the wall. This process narrows the true lumen, putting the patient at risk of embolus in the carotid segment.1,3,4 Should the clot break free, an embolic event to the ipsilateral eye or brain could occur.

ICAD usually occurs in the extracranial carotid segment; fewer than 10% of dissections occur intracranially.4 The extracranial ICA is more mobile and easily injured, as the ICA may be compressed against the first or second cervical vertebra.1,2,5

Minor events that involve a hyperextension or rotation of the necksuch as coughing, vomiting, sneezing, chiropractic manipulation and prolonged telephone usemay precipitate an ICAD in 25-41% of patients.2,4,6 This patients forceful head and neck turn likely caused her condition, though the extensive intracranial component suggests a possible arterial abnormality.

Dissections of the ICA rarely extend past the base of the skull or occur within the petrous and intracavernous sinus segments.3 Patients with spontaneous dissections may have an underlying arteriopathy due to a connective tissue disorder, such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome or Marfans syndrome.1,6

Acute or persistent pain along the pathway of the internal carotid artery, unilateral headaches and pupil miosis should alert you to the presence of an ICAD. Clinical manifestations of ICAD include:

Horners syndrome. Painful Horners occurs in 50% of cases.2 Postganglionic Horners results from damage to the sympathetic pathway distal to the superior cervical ganglion (SCG). In ICAD, the clot in the wall causes ischemia of the vasa nervosum or compression of the sympathetic fibers surrounding the affected carotid artery. Ipsilateral ptosis, miosis and facial anhidrosis over the nasal brow area result. Sweat glands to the cheek and chin are spared if the lesion is postganglionic or beyond the SCG.2,8

Unilateral head, face or neck pain. Ipsilateral head pain is present in 70-80% of ICADs;7 there may be orbital and periorbital facial pain.

Ipsilateral cerebral or retinal ischemia. This occurs within hours to days in about 80% of patients.1

Visual symptoms occur when an embolus from the damaged arterial wall travels to the ophthalmic artery and its branches, or from retinal hypoperfusion secondary to stenosis of the carotid artery. The ischemia may be temporary or permanent. In 41% of patients with extracranial ICAD, the time between the onset of symptoms, such as amaurosis fugax, and the onset of stroke ranged from a few minutes to 31 days.2,4,6,9

Ipsilateral cranial nerve palsies. These occur in about 12% of ICAD patients.The hypoglossal nerve is commonly affected due to direct compression or ischemia.1,2 Multiple cranial nerve palsies are possible.

|

| The right petrous, cavernous and supraclinoid carotid lumens were severely narrowed. |

Conventional four-vessel angiography has been the gold standard for diagnosing ICAD, but MRI and MRA have become the preferred noninvasive diagnostic and follow-up tools.1-3,6 MRI with fat-suppression differentiates small intramural hematomas from the surrounding soft tissue. Ultrasonography, though less sensitive than MRI or MRA, may show signs of stenosis. Dynamic helical computerized tomographic angiography detects dissecting aneurysms, but exposes the patient to high amounts of X-ray.2

Unless contraindicated, patients with spontaneous carotid or vertebral dissections should undergo anticoagulation treatment with intravenous heparin followed by oral warfarin, because 90% of infarcts in extracranial ICADs may be embolic in origin.1,4,6 Antiplatelet therapy also is necessary, because the mechanism for intracranial dissections is more hemodynamic, and because anticoagulants carry the risk of subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Patients should undergo MRA after three months of anticoagulation therapy. If vessel wall irregularities still exist, anticoagulation is continued for three months; otherwise antiplatelet treatment may begin.2,4,6 If anticoagulation therapy fails to relieve symptoms of ischemia, surgical treatment, such as balloon dilation or stenting, may be considered.2,6,10

Improvement usually occurs within three months. The prognosis depends on the severity of the ischemia before treatment. Complete resolution occurs in more than 50% of patients. The reported death rate is less than 5%. There is a 4% risk of a second ICAD. This risk decreases 1% each following year. Anticoagulation and antiplatelet therapy do not prevent recurrence.1,2,6

As clinicians, we must take a thorough history and pay attention to the presenting signs. Otherwise, ICAD may have devastating consequences, such as stroke. Until proven otherwise, consider a third-order Horners with an ipsilateral eye, head or neck pain of sudden onset to be the result of an ICAD.1

Ms. Petrilla, a fourth-year student at University of Houston College of Optometry, won second prize in Review of Optometrys recent Student Case Report Challenge with this paper.

1. Schievink WI. Spontaneous dissection of the carotid and vertebral arteries. N Engl J Med 2001 Mar 22;344(12):898-906.

2. Stapf C, Elkind MS, Mohr JP. Carotid artery dissection. Annu Rev Med 2000;51:329-47.

3. Bousson V, Levy C, Brunereau L, et al. Dissections of the internal carotid artery: three-dimensional time-of-flight MR angiography and MR imaging features. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1999 July;173(1):139-43.

4. Zetterling M, Carlstrom C, Konrad P. Internal carotid artery dissection. Acta Neurol Scand 2000 Jan;101(1):1-7.

5. Hughes KM, Collier B, Greene KA, Kurek S. Traumatic carotid artery dissection: a significant incidental finding. Am Surg 2000 Nov;66(11):1023-7.

6. Khimenko LP, Esham HR, Ahmed W. Spontaneous internal carotid artery dissection. South Med J 2000 Oct;93(10):1011-6.

7. Guillon B, Biousse V, Massiou H, Bousser MG. Orbital pain as an isolated sign of internal carotid artery dissection. A diagnostic pitfall. Cephalalgia 1998 May;18(4):222-4.

8. Biousse V, Touboul PJ, DAnglejan-Chatillon J, et al. Ophthalmologic manifestations of internal carotid artery dissection. Am J Ophthalmol 1998 Oct;126(4):565-77.

9. Ramadan NM, Tietjen GE, Levine SR, Welch KM. Scintillating scotoma associated with internal carotid artery dissection: report of three cases. Neurology 1991 July;41(7):1084-7.

10. Hemphill JC 3rd, Gress DR, Halbach VV. Endovascular therapy of traumatic injuries of the intracranial cerebral arteries. Crit Care Clin 1999 Oct;15(4):811-29.