|

A 63-year-old Hispanic male presented with a sudden onset of blurred vision and inferior visual field loss in the left eye that started about one hour before coming in. Because he was scared, he came immediately. His past ocular history was unremarkable. He began wearing OTC reading glasses approximately 15 years ago, and his medical history was significant for hypertension, coronary artery disease and back pain.

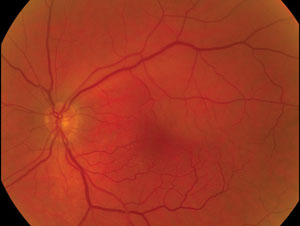

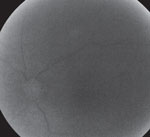

On examination, best-corrected visual acuity was 20/20 OU. Confrontation visual fields were full to careful finger counting in the right eye. In the left eye, there was an obvious inferior depression. This was also seen on Amsler grid testing. His pupils were equally round and 3+ reactive with a trace afferent pupillary defect on the left side. The anterior segment was unremarkable in both eyes. Dilated fundus exam of the right eye was normal. Exam of the left eye showed changes (Figure 1). An OCT and fluorescein angiogram (FA) were obtained and an early frame of the angiogram is available for review (Figure 2).

| ||

| Fig. 1. Above, fundus image shows the 63-year-old Hispanic male patient’s left eye. The patient reported sudden onset of blurred vision beginning one hour prior. Fig. 2. At left, a fluorescein angiogram of the same eye. |  | |

Take the Retina Quiz

1. What is the significant finding on the FA?

a. The FA is normal.

b. It shows a branch retinal vein occlusion (BRVO).

c. It shows a branch retinal artery occlusion (BRAO).

d. There is a delay in the arterial phase.

2. What is the correct diagnosis?

a. Anterior ischemic optic neuropathy.

b. BRVO.

c. Central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO).

d. BRAO.

3. How should this patient be managed?

a. Observation only.

b. Carotid artery work up, including Doppler studies.

c. CRP and sed rate.

d. Anti-VEGF injection.

4. What is the prognosis?

a. Return to normal visual function.

b. Painless progressive vision loss.

c. Will likely develop optic atrophy.

d. Has a good chance of developing neovascular glaucoma.

For answers, see below.

Diagnosis

It appears our patient has a BRAO involving the superior temporal artery of the left eye, although this may also represent a reperfused CRAO. The clinical findings are consistent with a BRAO because there is an area of retinal whitening superotemporal to the macula that begins along the arcade and extends inferiorly and stops adjacent to the macula. We observed a clear delineation of the retinal whitening—which represents ischemia and swelling of the photoreceptors—and the normal retina. Because it does not directly involve the fovea, the acuity remained 20/20, although threshold visual field testing shows a relative paracentral scotoma corresponding to the area of retinal whitening.

| |

| Fig. 3. The patient’s visual fields test results. |

It is possible this may have started out as a CRAO and reperfused itself before it had a chance to cause massive retinal ischemia, as is usually seen in a CRAO. The FA shows a significant delay in the arterial phase of the angiogram.

The image provided was shot at 30 seconds, and you can see the fluorescein dye just beginning to fill the arteries. In a normal patient, this happens by about 10 seconds.

| |

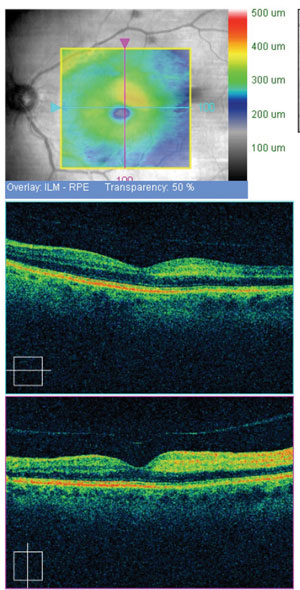

| Fig. 4. Images from the patient’s OCT evaluation. |

Discussion

Both BRAO and CRAO develop as a result of emboli that pass from other parts of the body, most commonly the carotid artery, into the eye and, depending on the size of the embolus, blocks blood flow to the retina, resulting in ischemia to the tissues. Larger emboli may completely block perfusion into the central retinal artery, whereas a smaller one may pass through the central retinal artery and occlude a branch or even a smaller arteriole. In some instances, the plaque may be visible on clinical exam, although we were not able to see the plaque in our patient, which is not unusual because the occlusion is not always permanent, but instead may last for only a few seconds or minutes. Though often transient, the damaging effects of the ischemia may be permanent. That’s why the diagnosis and management of BRAO and CRAO are time-sensitive. The duration of the occlusion is the most critical factor in determining visual recovery; the window of opportunity for recovering useful vision in a CRAO is between 90 minutes and 240 minutes.1 If it is less than 90 minutes, the retina may suffer no significant damage; more than 240 minutes, the retina will suffer massive irreversible damage. Our patient presented within 60 minutes from the time he noted visual changes, and it appears the embolus passed through the retinal circulation with only mild damage to the retinal tissue.

Treatment

If discovered at the earliest stage, ocular massage or re-breathing carbon dioxide may help to dislodge the embolus or provide enough dilation of the retinal artery to allow the plaque to pass.

Most BRAOs do not require any treatment, and visual recovery is dependent on the location and duration of the occlusion.

Our patient was lucky, since he maintained 20/20 acuity; however, his inferior visual field depression remained persistent.

He was referred to his cardiologist, and carotid artery studies were obtained and came back with minimal blockage.

1. Hayrey, SS. Prevalent misconceptions about acute retinal vascular occlusive disorders. Progress in Retinal and Eye Research, 2005;24:493-519.Retina Quiz Answers:

1) d; 2) d; 3) b; 4) a.