California HealthCare Foundation (CHCF) used a pattern-recognition learning process—deep learning—to detect diabetic retinopathy (DR), according to an article recently published in the Economist. CHCF, in partnership with EyePACS, challenged a community of data scientists to find a way to detect DR in fundus images for a grand prize of $50,000. Competitors were able to train statistical models of learning to detect signs of retinopathy, even in its more subtle presentations, the article says.

According to Benjamin Graham, PhD, assistant professor at the University of Warwick and winner of the competition, the computer agreed with a doctor’s opinion 85% of the time. “Computers could be used to give a second opinion, with differences in diagnosis being flagged for further review, or to highlight areas of interest in images to make it easier for the human grader to process them,” Dr. Graham says. “They don’t have to be 100% reliable to be useful—human graders certainly are not 100% reliable.”

| |

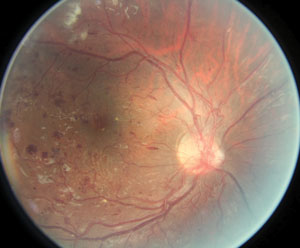

| Healthy and disease images, such as this fundus image showing diabetic retinopathy, were used to train computers to recognize the condition. Photo: EyePACS. |

Doctors agree on a diabetic retinopathy diagnosis 84% of the time, Jared Teo of the CHCF says in the article.

Additionally, Dr. Graham’s results showed that two computers agreed with each other 93% of the time, higher than the computer-doctor agreement. He suggests two possible explanations for the lack of agreement. “The computers are making systematic errors, and totally missing information available to the human grader, […] or the human graders make mistakes, and the computers have learnt to classify the images more accurately that humans. The truth is likely to be a mix of the two.”

The possibility of automated screening technologies carries both positives and negatives, according to Steven Ferrucci, OD, chief of optometry at the Sepulveda VA and professor at the Southern California College of Optometry. Nearly 15 years ago, he was involved in a pilot program that evaluated a tele-retinal program designed to remotely review diabetic patients’ fundus photos for DR. “It was clear that this system had its plusses, such as allowing care to patients who traditionally would not have access,” he says. However, “while we could often assess the retinopathy, it became apparent that this was simply a tool for screening one single aspect of the patient’s ocular health, not a full assessment.” The same limitation applies to this new technology as well, he says.

A computer program can be taught to look for specific signs of DR, but cannot provide a comprehensive exam, he explains. It may miss things like glaucoma or a peripheral retinal tear, putting the patient at further risk. The program cannot understand the intricacies of patient care either,

Dr. Ferrucci says. “Obviously, there are liability issues here that would need to be addressed. Where technology can certainly help take better care of our patients, […] it must be tempered against its inherent pitfalls.”