|

|

|

Q: I recently saw a patient referred from the local emergency department with a severe alkali burn (fertilizer) to the conjunctiva and cornea. His eye was irrigated copiously for 40 minutes for the chemical insult prior to presenting to our office. How valuable is pH testing in cases like this one, i.e., those that have been copiously irrigated? Is it considered passé?

A: Litmus paper can be helpful in certain instances; however, it does not take precedence over immediate and aggressive irrigation following an ocular chemical injury.

“Alkalis penetrate the conjunctiva and cornea quite readily, while acids precipitate on the surface, which tends to limit their penetration and injury severity. Consequently, alkali injuries are generally more damaging than acid injuries,” says Christopher J. Rapuano, MD, director of cornea service at Wills Eye Hospital in Philadelphia. Examples of alkali offenders include ammonia (fertilizers or refrigerants), lye (cleaning agents) or lime (building materials). Damage can vary depending on the type of chemical, how much entered the eye and when initial irrigation began.

|

|

|

|

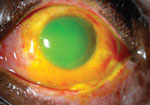

There is a total corneal epithelial defect and a large conjunctival epithelial defect after a severe chemical injury in the left eye of this patient. Note that the conjunctiva has begun to epithelialize nasally, near the canthus.

|

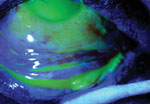

Using cobalt blue light after fluorescein dye, the corneal and conjunctival

epithelial defects are highlighted. Note the large bulbar conjunctival epithelial defect, but the majority of the palpebral conjunctival epithelium is intact. |

|

| Photos: Chris J. Cakanac, OD | ||

The primary goal of irrigation following a chemical injury is to reestablish a pH level of approximately 7.5, the pH level of healthy human tears, Dr. Rapuano explains. “If the initial pH is much higher or lower than that, it will usually take more fluid for longer periods of time than if the initial pH is close to 7.5,” he says. Consequently, he adds, there is no exact quantity of fluid or duration of effort established as a minimum to achieve adequate irrigation.

It is in this situation that pH testing is useful: first, to check initial pH before irrigation (if possible) or upon arrival after being irrigated elsewhere, and then once or twice at 20-minute intervals to monitor irrigation efforts. Note, however, that the effectiveness of irrigation by evaluating with litmus paper has never been scientifically studied.1

Ocular irrigation can be performed by dripping either water or saline from an IV bag or nasal cannula, or using a Morgan lens, Dr. Rapuano says. He suggests considering the possibility that foreign material—for example, wet concrete, which is alkaline in nature—might adhere to the eye if the pH remains abnormal after copious irrigation. Check the lid area and fornix with double eversion, then carefully remove any particulate material and excise devitalized tissue.

J. James Thimons, OD, ophthalmic medical director at Ophthalmic Consultants of Connecticut, points out that pH testing can also help in certain unique cases. “In patients exposed to chemical agents, pH testing is a useful adjunctive tool for the clinician in cases where either the agent is unknown or the actual pH is outside of the routine chemicals that are seen in primary care practice,” he says.

However, Dr. Thimons cautions, the somewhat limited shelf-life of test strips can confound pH testing. “Due to infrequent use, test strips can become ineffective and demonstrate inaccurate pH levels,” he says. “The remedy to this concern is to periodically test the strips on normal patients to ensure accuracy.” Error can also result from the presence of too little or too much tear film, which can alter pigment levels in the strip response, and from using the strips too soon after irrigation. n

1. Foster CS, Azar DT, Dohlman CH. Smolin and Thoft’s The Cornea: Scientific Foundations and Practice. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2004.