| Access sessions, exhibit hall and special events through the Academy event planner. |

Not all optometrists are low vision gurus, but everyone sees patients who could benefit from this intervention—and that doesn’t have to mean a referral, according to Erin Kenny, OD, FAAO, and Carlo J. Pelino, OD, FAAO. The two lecturers spent Wednesday morning discussing several common ocular conditions that often leave patients with vision loss. Even preliminary recommendations for low vision aides can go a long way for patients with vitreomacular traction and macular holes, diabetic retinopathy, glaucoma, retinal detachment and retinitis pigmentosa. Attendees learned about the visual sequelae from these pathologies and some of the common low vision management techniques that can help.

Traction and Holes

The duo began with vitreomacular traction and macular holes, first reviewing how the vitreoretinal interface becomes detached in the first place.

“Everyone’s vitreous, for the most part, will detach in the same way,” Dr. Pelino explained. “It will start by detaching on one side, then the other and finally the fovea will detach completely.”

This can cause reduced vision, the most concerning being a central scotoma, Dr. Kenny added.

“During the exam, the patient may be fine with the distance acuity, but struggle with near vision,” she noted. “That’s because distance testing often focuses on individual letters while near vision testing uses continual text, which is more affected by that central scotoma.”

Clinicians should recommend near vision glasses and stay away from progressives, she advised. In addition, eccentric viewing training can help the patient learn to shift the scotoma away from their central viewing. “Adding magnification can really make reading possible for some of these patients,” according to Dr. Kenny.

|

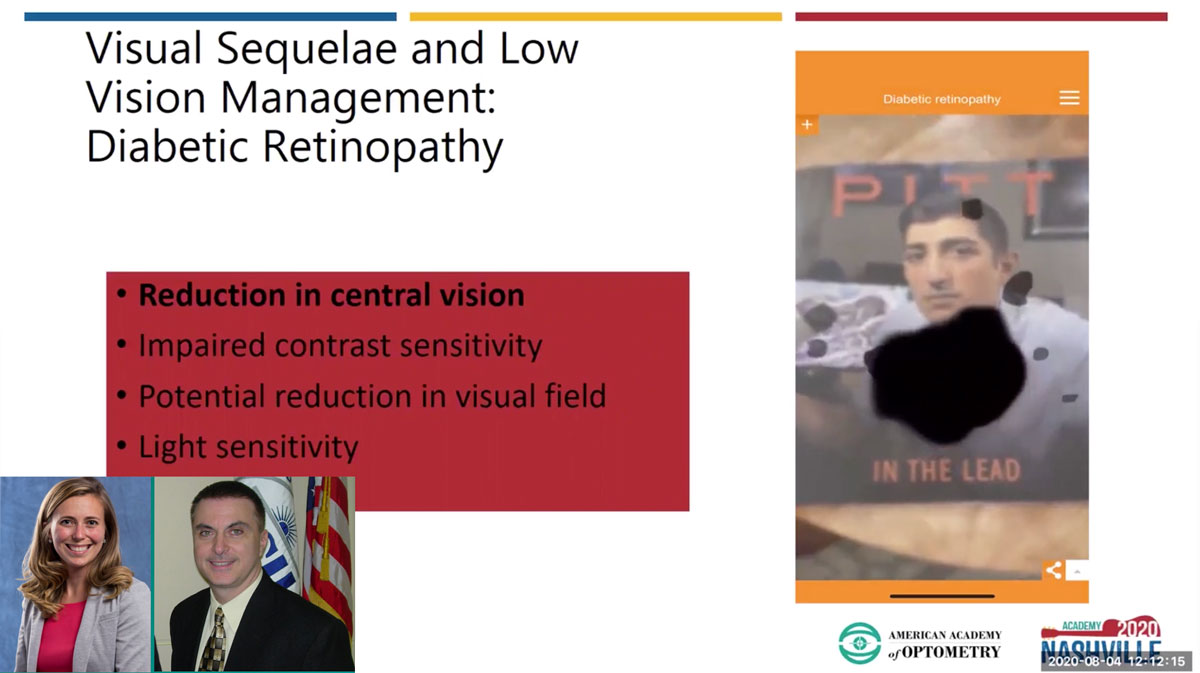

| Dr. Kenny demonstrated the visual effects of diabetic retinopathy, including progressing central vision loss and reduced contrast sensitivity. Click image to enlarge. |

Diabetes Epidemic

Next on the list was diabetes, which affects nearly 10% of the American population, “so it’s something we all see, Dr. Pelino stressed. And if left unchecked, the condition can lead to sight-threatening diabetic retinopathy (DR). Clinicians should get into the habit of screening patients for signs of diabetes beyond simply asking about the patient’s hemoglobin A1C, he added. Cholesterol levels, blood pressure, anemia, sleep apnea and smoking can all exacerbate retinopathy, he said.

“Vitamin D levels are important for all individuals, whether they have diabetes or not, but it’s especially important for these patients because it has multiple roles,” Dr. Pelino said. “Most people are happy with levels around 25ng/mL, but studies really show it should be 32ng/mL or higher because vitamin D helps to decrease inflammation, allows insulin to be released and allows the receptors to work better.”

DR can affect all aspects of a patient’s vision, but Dr. Kenny focused on central vision loss, walking attendees through a quick review of calculating the right magnification power. The key is starting with the patient’s visual goal and an accurate near refraction, she said.

“If a patient is holding a newspaper at 33cm, you will need a +3.00D add, but if they hold it at 25cm, they should use +4.00D add,” she explained. “That add has to match up with the working distance. The power calculation won’t work if that’s not accurate.”

As for the low vision technology, she recommended starting with full field microscopes or hand magnifiers—and don’t forget about proper illumination, she warned. “Patients need the magnification, but they also need the improved contrast that comes with better illumination.”

If they have a smartphone, accessibility settings can make a huge difference, Dr. Kenny added. She showed her audience how to access a zoom option and a magnifier on the iPhone, which is “definitively something you should be showing your patients if they have a smartphone,” she said.

Lighting is Key

Glaucoma is something we see every day, Dr. Pelino said, and it’s a chronic progressive optic neuropathy that’s really the end-stage of many other conditions. It’s also a three-pressure disease, not just intraocular pressure (IOP).

“Think of the normal tension glaucoma patient,” he explained. “Their IOP is in the normal range, but their intracranial pressure might be low, or their ocular perfusion pressure might be low. We need to get away from just looking at IOP and instead start looking closely at the optic nerve,” he advised.

Glaucoma, particularly primary open-angle, starts with peripheral field loss and progresses to central field loss, which can be accompanied by reduced contrast sensitivity and increased glare sensitivity. For these patients, the lighting is crucial, according to Dr. Kenny.

“Increased age requires increased illumination due to the loss of light transmittance and light scatter of short wavelengths, and this is true for any patient, not just the glaucoma patient or your low vision patient,” she said. “As we get older, we need more light.”

When it comes to recommending lighting sources, it’s important to understand that the closer the light is to the material, the more illumination you will have—it’s more about distance to the target and less about the wattage of the lighting source itself, she noted.

To combat glare, Dr. Kenny prefers to start with the transmittance before playing around with tints and filters—but be careful about the type of glare you are talking about, she warned.

“If a patient says glare is really bad, make sure you ask if it’s glare from the computer screen, the phone, TV or if the glare is particularly bad outside,” she said. “Depending on the type of glare, that will change our approach.”

She prefers fit-overs or clip-ons in lieu of transition lenses for those with low vision because they already have a hard time adapting to lighting changes; a transition lens isn’t going to help.

|

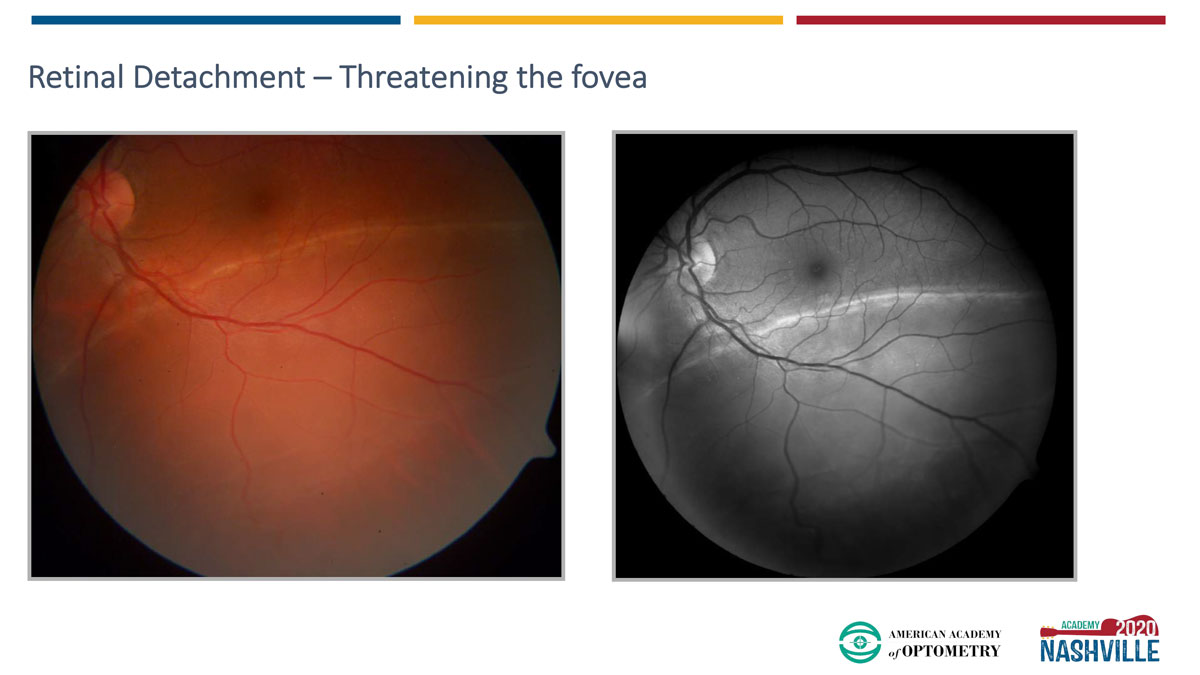

| Dr. Pelino’s 29-year-old patient with high myopia presented with a complaint of superior vision loss. The dilated fundus exam revealed a retinal detachment threatening the fovea—a true emergency. Click image to enlarge. |

Lost Connection

Next up was retinal detachment, which, depending on the type, can present with anything from flashes and floaters to a “curtain” over part or all of their visual field, explained Dr. Pelino.

These patients need a referral to a retina specialist for surgical intervention, he said, whether that’s laser retinopexy, a scleral buckle, cryotherapy or C3F8 or SF6 “gas bubble” as a tamponade.

They will also need help adapting to the post-op visual sequelae, if present. If they have complete vision loss, optometrists shouldn’t shy away from recommending auditory options, such as books on tape, and referring patients to state agencies for the visually impaired. “These are goldmines for specialists and therapists for low vision aides,” Dr. Kenny said. State agencies can help patients with everything from vision and vocational rehabilitation to orientation and mobility training, assistive technology and teachers of the visually impaired.

It’s a Gene Thing

The last condition Drs. Kenny and Pelino discussed was retinitis pigmentosa (RP). Even though it’s a genetically driven disease, RP tends to come with syndromes and ODs should be prepared to dig a little deeper when diagnosing these patients. Be on the lookout for Kearns-Sayre syndrome, Refsum disease, gyrate atrophy and even cancer-associated retinopathy or other rare conditions, Dr. Pelino noted.

The most well-known, and early, visual sequelae is night blindness. Patients can also experience photopsia, peripheral vision loss and, in advanced cases, central vision loss.

A host of low vision aides will come in handy for patients with RP, depending on the task at hand. Prisms may help patients with peripheral vision loss, as can a referral for orientation and mobility training.

Again, lighting is a crucial. “I’ve even had patients completely remodel their homes to ensure they have the best lighting possible,” Dr. Kenny explained. But patients don’t have to go that far, and most can have a flashlight handy when moving around at night, according to Dr. Kenny.

Lastly, genetic testing is becoming more mainstream with the approval of Luxturna (Spark Therapeutics), and Drs. Kenny and Pelino encouraged ODs to discuss the screening options with their patients. One genetic testing kit, ID Your IRD, is free and easy to use, Dr. Kenny said.

Dr. Kenny concluded with a final word of advice: “We want you to be confident with systemic conditions with ocular pathologies and be familiar with primary care low vision recommendations […] There is no problem starting to introduce low vision management in the primary care setting—a lot of patients would benefit from it and appreciate it.”