|

A 64-year-old female presented one day after receiving a 1.25mg intravitreal injection of bevacizumab (Avastin) in her right eye. The patient had developed a small subconjunctival hemorrhage and a “blue patch” on her right lower eyelid shortly after the procedure. The patch had reportedly enlarged throughout the previous day and now encompassed both the right lower and upper eyelids.

The patient’s eye was red and swollen and tender to the touch. She stated her vision was blurry, noting intermittent double vision while watching television. She said dabbing her eye drew blood.

Ocular history included exudative age-related macular degeneration with choroidal neovascularization in both eyes, for which she was receiving intravitreal anti-VEGF injections every eight weeks. Additionally, the patient had grade 2+ nuclear sclerotic cataracts in both eyes. Her medical history was positive for polycythemia vera, protein S deficiency, erythema nodosum and type 2 diabetes mellitus. The patient was placed on a 10mg daily regimen of the direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) medication Xarelto (rivaroxaban, Janssen Pharmaceuticals) for her protein S deficiency. Additionally, she was taking 3mg of prednisone orally for recent-onset pyoderma gangrenosum and receiving insulin injections of Lantus (Sanofi) 14 units daily and NovoLog (Novo Nordisk) 6 units with meals to manage her diabetes. Her polycythemia vera was treated with phlebotomies as needed.

The patient’s entering distance visual acuities were 20/60 OD and 20/40+ OS, with no improvement on pinhole testing. Her visual acuity had been 20/25 OD during the previous day’s examination. She did not have a relative afferent pupillary defect, nor did she report pain upon eye movement, although she did have some difficulty moving her right eye.

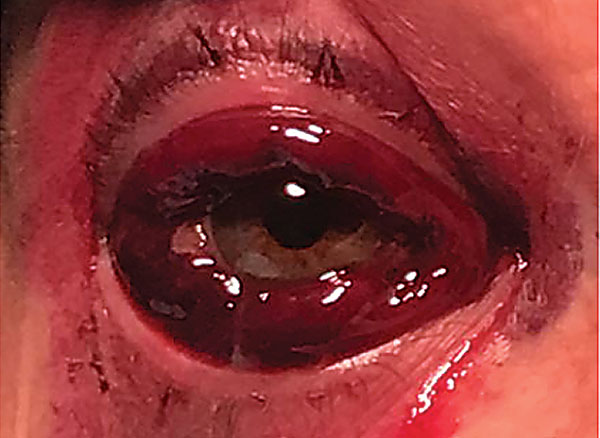

Upon examination of the anterior segment, the patient’s right eye displayed 2+ to 3+ ecchymosis of both the right upper and lower eyelids (Figure 1). The patient had a 3+ subconjunctival hemorrhage with persistent leakage of blood, and blood was visualized in the patient’s tear meniscus (Figure 2). Her right eye was not proptotic. There were no signs of anterior chamber reaction, hypopyon, hyphema or infection, and intraocular pressures were within normal limits. Examination of the posterior segment, as well as of the left eye, was unremarkable.

|

|

Fig. 1. Ecchymosis of the upper and lower eyelids. Note the blood mixed in with the tears in the medial canthal area. Click image to enlarge. |

Diagnosis

The examination was directed to differentiate between a severe anterior subconjunctival hemorrhage and a retrobulbar hemorrhage (RBH), which is an ocular emergency that poses a significant threat to vision.1 Findings prompting suspicion of RBH include sudden onset of severe pain, proptosis, ophthalmoplegia, deterioration in visual acuity, subconjunctival hemorrhage, increased intraocular pressure and pupil abnormalities such as a relative afferent pupillary defect.2,3

Salient factors that helped rule out a diagnosis of RBH in this instance included normal intraocular pressure and the absence of pupil abnormalities, proptosis and pain on eye movement. The decreased visual acuity and intermittent diplopia was explained by the persistent blood in the tear lake and mild restriction of eye movement by the protruding subconjunctival hemorrhage. Furthermore, the location of the previous day’s injection, paired with the visualization of the continued hemorrhaging, allowed for localization of the source of bleeding.

Anti-VEGF injections are performed at a relatively anterior location, 3mm to 4mm posterior to the limbus, so as to enter the pars plana of the ciliary body.4 Conversely, the most common causes of RBH include retrobulbar anesthesia and blunt force trauma, neither of which our patient experienced.5

Treatment for acute RBH requires the release of pressure from within the orbit.1 The transcutaneous transseptal orbital decompression approach allows for drainage of an orbital hematoma, while lateral canthotomy and inferior cantholysis allow for orbital decompression but do not evacuate pooled blood from within the orbit.1

Discussion

Subconjunctival hemorrhages are typically benign and self-limiting conditions that produce minimal symptomology. When seen in non-anticoagulated patients, intervention is usually not required.6 Acute subconjunctival hematoma formation, as seen with our patient, is a rare occurrence.

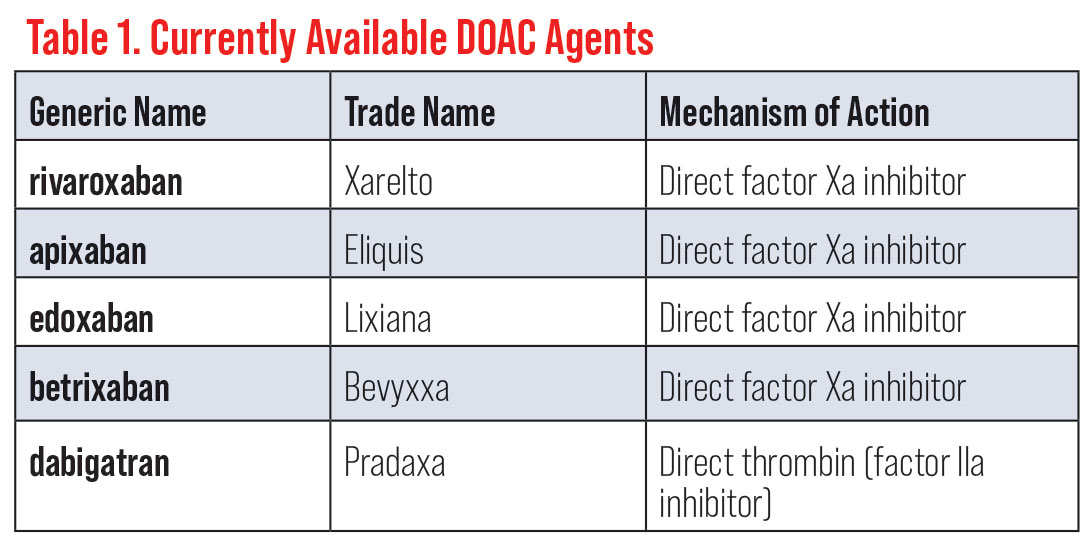

Anticoagulation is indicated for treatment and prevention of thromboembolytic events for patients in a hypercoagulable state (such as protein S deficiency).7 For nearly 70 years, heparin and vitamin K antagonists, such as Coumadin (warfarin, Bristol-Myers Squibb), have been mainstay pharmacological agents used for these patients.7 While the benefits of these therapies have been well established in a wide array of thromboembolic disorders, limitations such as a narrow therapeutic range, food and other drug interactions and frequent laboratory monitoring of the international normalized ratio (INR) have encouraged efforts to develop more targeted therapies.8 More recently, DOACs have risen to prominence with a purported goal of offsetting some of the limitations of warfarin and heparin (Table 1).

Currently, there is no FDA-approved equivalent to the INR for measuring the anticoagulant effect of DOACs. Qualitative coagulation assays such as activated partial thromboplastin time, thrombin time and prothrombin time are insufficient to assess the degree of anticoagulant effect as seen with INR for management of warfarin therapy.8 Quantitative measures such as anti-factor Xa level, plasma drug concentration, dilute thrombin time and ecarin thrombin time are able to directly assess anticoagulation effects.8

Unfortunately, standardized therapeutic ranges for DOACs have not been established and quantitative test results have not been correlated with clinical outcomes.8 If a patient taking Xarelto or Eliquis (apixaban, Pfizer) experiences uncontrolled bleeding, the anticoagulant antidote Andexxa (andexanet alfa, Portola Pharmaceuticals) can be administered.9 Andexxa has been shown to rapidly reverse the anticoagulant effects of both of these medications.9 Andexxa may also be effective in reversing the anticoagulant effect of other direct and indirect factor Xa inhibitors.9

|

Fig. 2. Extensive protruding subconjunctival hemorrhage. Click image to enlarge. |

Outcome

Due to the anterior location of the subconjunctival hemorrhage, a pressure patch was placed over the patient’s right eye in an attempt to tamponade the bleeding. The patient was instructed to leave the patch in place for three hours before removing it to determine if the bleeding had ceased. After the appropriate amount of time had passed, the patient called to inform us that the bleeding had been controlled. She was instructed to use cold compresses to reduce swelling and keep her head elevated while sleeping.

Dr. Christenson is a recent graduate of the Pacific University College of Optometry in Forest Grove, OR. He has no financial interests to disclose.

Dr. Skorin is a consultant in the Department of Surgery, Community Division of Ophthalmology at the Mayo Clinic Health System in Albert Lea and Austin, MN. He has no financial interests to disclose.

1. Ebenezer V, Ramalingam B. Retrobulbar hemorrhage—a literature review. European J Molec Clin Med. 2020;7(4):1570-3. 2. Joseph E, Zak R, Smith S, et al. Predictors of blinding or serious eye injury in blunt trauma. J Trauma. 1992;33(1):19-24. 3. Allen M, Perry M, Burns F. When is a retrobulbar haemorrhage not a retrobulbar haemorrhage? Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;39(11):1045-9. 4. Yorston D. Intravitreal injection technique. Community Eye Health. 2014;27(87):47. 5. Shek KC, Chung KL, Kam CW, et al. Acute retrobulbar haemorrhage: an ophthalmic emergency. Emerg Med Australasia. 2006;18(3):299-301. 6. Nguyen TM, Phelan MP, Werdich XQ, et al. Subconjunctival hemorrhage in a patient on dabigatran (Pradaxa). Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31(2):455. 7. Franchini M, Liumbruno GM, Bonfanti C, et al. The evolution of anticoagulant therapy. Blood Transfus. 2016;14(2):175-84. 8. Chen A, Stecker E, Warden BA. Direct oral anticoagulant use: a practical guide to common clinical challenges. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(13):e017559. 9. Abramowicz M, Zuccotti G, Pflomm J. Andexxa—an antidote for apixaban and rivaroxaban. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2018;60(1549):99-101. |