A 20-year-old Asian male presented to optometrist Robert Wooldridges Salt Lake City practice for a general eye examination with no visual complaints. But this case was anything but simple.

Consider: The patients medical history is positive for congenital heart disease, for which he has had multiple surgical procedures of an unspecified nature. He also has congenital hearing loss. Though he has some hearing, he largely relies on lip reading. The patient is adopted, so family history is unknown. He is Korean-American by heritage.

Examination revealed -6.00D of myopia O.U., with best-corrected acuity of 20/20 O.U. On slit lamp examination, the anterior segments were quiet O.U. Intraocular pressure measured 20mm Hg O.D. and 21mm Hg O.S.

Intraocular pressure is but one risk factor to consider when deciding whether to initiate treatment on glaucoma suspects.

On dilated fundus examination, the patient had large oval discs.

The cups are correspondingly large, and horizontally oval, with a cup-to-disc ratio of 0.80 x 0.60 O.U.

Initial visual fields show mild decreased central sensitivity in the right eye, and inferior changes in the left.

On a follow-up visit two weeks later, an afternoon pressure was 19mm Hg O.U. Three months later, his morning pressures were 22mm Hg O.D. and 20mm Hg O.S. The visual fields were repeated at this time and appeared normal. However, HRT evaluation showed that both nerves are outside normal limits as judged by the Moorfields analysis.

How would you approach this case? Would you initiate glaucoma therapy or monitor the patient? This case is an example of the complicated issue of whether to treat or not to treat such patients. Here, well look at some of these controversies you and your colleagues face when caring for glaucoma suspects and what the Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study, better known as OHTS, tells us about assessing and managing these patients.

Risk Factors

There were some important factors to consider with this patient, namely:

The patient is Asian. There are significant reports in the literature that normal-tension glaucoma is more common in Japan than in the Western Hemisphere, Dr. Wooldridge says. So the fact that this patient is Asian, even though he is not of Japanese descent, may place him at a greater risk of developing normal-tension glaucoma.

The patient has undergone heart surgery. This may have resulted in decreased ocular perfusion, another risk factor for glaucoma. Perhaps that could explain why he has large cups, although Dr. Wooldridge does not subscribe to that theory.

The patient is hearing impaired. So the last thing he wants is to be visually impaired as well, Dr. Wooldridge says.

The patient is only 20 years old. OHTS looked at the risk for [developing glaucoma within] five years, Dr. Wooldridge says. With this guy being 20 years old, I had to worry not just about five years, but the cumulative risk over many years.

The family history is unknown. Because the patient was adopted, the patient did not know if there was a history of glaucoma among his birth family.

After he and the patient discussed options, risks and benefits, Dr. Wooldridge initiated treatment with Travatan (travoprost, Alcon) 1 drop q.d. in both eyes. One year later, the patients IOP remains in the high teens O.U. There is no apparent damage to the optic nerves and no signs of progression to glaucoma.

Sowing OHTS

Fortunately, results of OHTS offer information that can assist you in your clinical decision-making.1,2 This large national study was designed to:

Determine whether medical reduction of IOP could prevent or delay field loss and/or nerve damage in patients with ocular hypertension (OHT).

Describe baseline demographic and clinical factors that predict which patients develop primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG).

Produce a natural history of ocular hypertension, to aid clinicians in identifying patients at greatest risk for damage and to quantify risk factors for development of glaucoma.

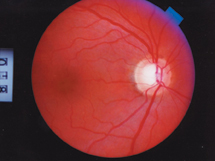

This ocular hypertensive patient has a healthy-looking fundus. Pressure-lowering medications may be necessary to keep it that way.

The study design included 1,636 patients ages 40-80 with IOP of 24-32mm Hg in the study eye, and 21-32mm Hg in the fellow eye. All patients randomized for the study had a normal visual field and optic nerve. Topical medical treatment only was used for this study. No patients had laser treatment or surgery as part of the study. Treatment goals were to lower the pressure below 24mm Hg and by a minimum of 20%.

At the end of five-year median follow-up, the prevalence of glaucoma in the observation group was 9.5%. The prevalence of glaucomatous damage in the medication group was 4.4%. This represents a greater than 50% reduction in risk of developing glaucoma over a five-year span. The difference in the prevalence of glaucoma in the observation group and in the medication group continues to increase with follow-up beyond five years. The study concluded that topical medication was effective in delaying or preventing the onset of POAG in persons with elevated IOP. Although this does not imply that all patients with borderline or elevated IOP should receive medication, clinicians should consider treatment for individuals with OHT who are at moderate or high risk for developing POAG.

A multivariate risk analysis of the patients found that the following were risk factors for the development of glaucomatous damage: older age, higher IOP, greater pattern standard deviation on visual fields, thinner central corneal thickness, and larger vertical cup-to-disc ratio.

Factors not predictive for damage were: family history, mean deviation, corrected pattern deviation, myopia, migraine, cerebral vascular accident, high or low blood pressure, use of oral beta blockers or calcium channel blockers, and diabetes.

Race is of specific interest in these patients, Dr. Wooldridge says. While population-based studies clearly indicate that African Americans have a 4-5 times increased prevalence of glaucoma in the United States, the OHTS data suggest that this racial difference may be due to thinner central corneas and larger cup-to-disc ratios in African-Americans. In other words, race itself does not appear to be the issue, but rather that African-Americans tend to have thinner corneas and larger cups.

A more recent study also found that black patients have significantly thinner central corneas than white, Asian or Hispanic patients. CCT averaged 551.16m for the total population and 535.46m for blacks.3

Patient Profile

So what do these findings mean to everyday clinical practice? Although OHTS found that medical therapy lowered the risk for progression to glaucoma, that doesnt mean you should start every patient on drops.

You have to develop a patient profile with respect to what risk factors they have for any of the different types of glaucoma, says Thomas L. Lewis, O.D., Ph.D., president of the Pennsylvania College of Optometry. Dr. Lewis is principal author of the AOAs Optometric Clinical Practice Guideline: Care of the Patient with Open-Angle Glaucoma.

Although OHTS says that family history is not a risk factor for progression to glaucoma, other studies have shown that patients who have a sibling with glaucoma are more likely to develop glaucoma themselves.

Another consideration: any systemic problems that could contribute to the development of glaucoma, including perfusion problems to the head and neck region, diabetes, or any type of vasospastic condition. Other systemic problems that may increase the patients risk of developing glaucoma include hypertension, diabetes, atrial fibrillation and even migraine (migraines are vasospastic, so even when the migraine subsides, the vasospastic process continues).4

Given this information, suppose a patient presents with optic nerve or visual field changes, but IOP is normal. You have to make the differential diagnosis of whether the optic nerve head or visual field changes are caused by something else or most likely caused by glaucoma, Dr. Lewis says. And, if you think its caused by glaucoma, what are the risk factors that they have for low-tension glaucoma.

If you determine that the patient has risk factors for normal tension glaucoma, youll need to lower IOP further.

Corneal Controversy

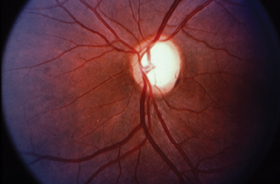

When evaluating risk factors for glaucoma, pay attention to the optic nerve. Notching of the neuroretinal rim, as in this patient, is 87% specific for glaucoma.

One risk factor that raises questions: central corneal thickness (CCT). When H. Goldmann first developed his tonometric technique, he assumed a central corneal thickness of 0.5mm.5 However, we now know that central corneal thickness varies.

We also know that patients who have thicker corneas may get artificially high IOP readings, while those with thinner corneas may get artificially low readings. That means an ocular hypertensive patient with IOP of 24mm Hg in both eyes may really have IOP of 27-29mm Hg.

Even if this patient has no visual field defects or discernible optic nerve changes, it will put them at a much higher risk if you put them at a 20- to 30-year life expectancy, says Bridgeton, N.J., optometrist Robert M. Cole, III. So I would be inclined to initiate treatment on that patient.

By contrast, if the patients IOP measures 24mm Hg, but he has an extremely thick cornea, Dr. Cole says he would feel comfortable monitoring this patient. Findings about the effects of CCT on intraocular pressure are a real breakthrough, Dr. Cole says. In my opinion its already become a standard of care to assist you in making these tough decisions.

Thinner central corneas also are an independent risk factor for developing glaucoma, OHTS found. In other words, even if adjusted IOP is within normal limits, patients with thinner corneas are at greater risk for developing glaucoma, according to OHTS.

Still, caution is the watchword. Suppose, for example, a patient presents with IOP of 20mm Hg O.D., no visual field loss and no discernible optic nerve changes, but that patient has a thin cornea. Some practitioners are going to begin treatment for that particular patient because, according to OHTS, they have a higher likelihood of developing glaucoma, says Carolina Beach, N.C., optometrist James L. Fanelli.

Still, Dr. Fanelli says he would opt to monitor the patient instead. While OHTS shows patients with thinner corneas generally have a higher likelihood of developing glaucoma, especially if their pressures are higher, it does not determine a cause-and-effect relationship, he says.

This brings us back to the importance of developing a risk profile. This risk profile should consider CCT, IOP, optic nerve characteristics, visual fields and optic nerve imaging.

All of those things play a role and not always the same role in the same patient, Dr. Fanelli says. For example, in one patient I may weigh more heavily on visual field findings, where with someone else I may not weigh as heavily on visual field findings, but might pay more attention to central corneal thickness or optic nerve characteristics.

Depending on the appearance, Dr. Fanelli says, he may give the optic nerve more weight than other risk factors. For example, if the exam reveals a thin neuroretinal rim, or if it reveals a plush neuroretinal rim in one meridian with peripapillary atrophy, he says, Im going to discount pressures and central corneal thickness in those patients, and Im going to pay more attention to the optic nerve.

Age-Old Question

The patients age also factors into your decision about whether to initiate treatment. The patients age is critical because the older they are, the less life expectancy they have, Dr. Cole says.

Suppose Mrs. Smith, a 75-year-old white female, presents with mild optic nerve changes and IOP of 24mm Hg. Now, suppose Miss Jones, a 25-year-old black female also presents IOP of 24mm Hg, but has thin corneas and no discernable optic nerve changes.

Dr. Cole says he would be more inclined to begin treatment on Miss Jones than on Mrs. Smith. Assuming Mrs. Smiths life expectancy is another 5-10 years, she would suffer little vision loss that would affect her lifestyle. By contrast, Miss Jones might be blind by age 75.

In Mrs. Smiths case, you would still consider her overall health in making the decision. You might also consider whether the cost of medications is justified, especially for senior citizens who are on fixed incomes.

Setting a Target

Now, say youve decided to treat the patient. Theres still the question of what target pressure to set.

The Advanced Glaucoma Treatment Study suggests that you try to lower IOP to at least 18mm Hg.6 Other studies suggest reducing IOP to 12mm Hg or less, particularly in patients with normotensive glaucoma. OHTS used a target reduction of 20%, while others suggest 30%.

There is no correct answer. Given different ages and different corneal thickness, what youre talking about is establishing a different target pressure for the two patients, Dr. Cole says.

The more advanced the disease, the lower your target pressure needs to be to stop progression, Dr. Lewis adds. [With] earlier onset of disease, you dont have to get the target pressure quite as low.

There appear to be no right or wrong answers when following glaucoma patients and determining when to treat. Rather, you must undertake an in-depth decision-making process that assesses all the patients risk factors, the likelihood of progression to glaucoma and how much any anticipated vision loss will affect the patients quality of life.

1. Kass MA, Heuer DK, Higginbotham EJ, et al. The Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study: a randomized trial determines that topical ocular hypotensive medication delays or prevents the onset of primary open-angle glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol 2002 Jun;120(6):701-13; discussion 829-30.

2. Gordon MO, Beiser JA, Brandt JD, et al. The Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study: baseline factors that predict the onset of primary open-angle glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol 2002 Jun;120(6):714-20; discussion 829-30.

3. Shimmyo M, Ross AJ, Moy A, Mostafavi R. Intraocular pressure, Goldmann applanation tension, corneal thickness, and corneal curvature in Caucasians, Asians, Hispanics, and African-Americans. Am J Ophthalmol 2003 Oct;136(4):603-13.

4. Fingeret M. Clinical decision-making in glaucoma. American Academy of Optometry lecture, December 2003.

5. Peplinski L, Torkelson K. Normalp-tension glaucoma and central corneal thickness. Optom Cis Sci 1999 Aug;76(8):596-8.

6. The Advanced Glaucoma Intervention Study (AGIS): 7. The relationship between control of intraocular pressure and visual field deterioration.The AGIS Investigators. Am J Ophthalmol 2000 Oct;130(4):429-40.