|

A 13-year-old Hispanic male presented complaining of gradual visual loss over the past year. The loss was greater in the right eye than the left. His brother stated that he was diagnosed with macular degeneration two years earlier in Cuba.

The patients medical history is unremarkable, and he reported no medication use. He was a product of a full-term pregnancy and normal delivery. The patients father has heart disease.

Best-corrected visual acuity was 20/200 O.D. and 20/50 O.S. Extraocular motility was smooth and full. Pupils were round and reactive to light with no afferent pupillary defect. Humphrey fields revealed paracentral visual field defects in both eyes. Ishihara color plates were 9/10 O.U. Slit lamp exam was unremarkable. IOP measured 18mm Hg O.D. and 20mm Hg O.S.

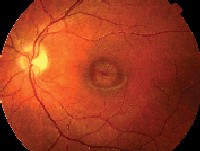

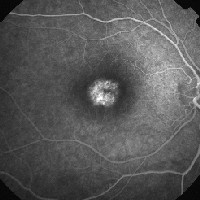

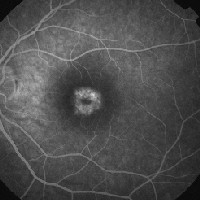

Dilated fundus exam revealed the presentation shown in figures 1 and 2. Findings from fluorescein angiography are shown in figures 3 and 4.

Take the Retina Quiz

1. Which is the best clinical description of each macula?

a. Chorioretinal scar.

b. Choroidal neovascular membrane.

c. Bulls eye maculopathy.

d. Macular hole.

2. Based on the information above, what would NOT be in your differential diagnosis?

a. Stargardts disease.

b. Progressive cone dystrophy.

c. Central areolar choroidal dystrophy (CACD).

d. Presumed ocular histoplasmosis syndrome (POHS).

3. Which test would be most beneficial in diagnosing this patient?

a. Optical coherence tomography.

b. Electroretinogram.

c. B-scan ultrasonography.

d. Both a and b.

4. What is the correct diagnosis for this patient?

a. Stargardts disease.

b. Progressive cone dystrophy.

c. CACD.

d. POHS.

|

| 1, 2. Fundus photos (O.D. left, O.S. right) show suspicious macular lesions. |

Discussion

This patient has bulls-eye maculopathy in each eye, so we must rule out several diagnoses that can present with similar-appearing lesions, including two of the more common hereditary macular dystrophies: Stargardts macular dystrophy and progressive cone dystrophy.

Several ancillary tests helped us rule out both diagnoses and ultimately diagnose our patient with central areolar choroidal dystrophy.

CACD is a rare macular dystrophy that primarily affects the choroid. It occurs bilaterally and usually presents in early childhood to late adulthood.1 There is no predilection for gender or race.1

CACD is hard to classify and recognize because definite pedigree patterns are scarce. Most patterns observed are autosomal dominant, but there have been reported cases of autosomal recessive inheritance.1 The autosomal dominant cases have been associated with the peripherin/RDS (retinal degeneration slow) gene as well as other loci.2

Our patient said that his mother was most likely affected, so his disease probably was inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion. (The mother was in Cuba and could not present for an ocular examination.)

CACD can present with early bilateral macular changes. These have been described as fine, mottled depigmentation, indicating a pigment epithelial dystrophy.3 Typically, no flecks or drusen are present in this type of chorioretinal dystrophy.

Continued progression of the disease results in a symmetric, sharply defined bulls-eye area of geographic atrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium in the macula. There are varying degrees of choriocapillaris loss within the area of RPE atrophy.

The RPE atrophy usually enlarges concentrically, but it does not exceed 3 to 4DD. Then the intermediate to large choroidal vessels will become visibly apparent. There has been minimal to no evidence of atrophy of the intermediate and large choroidal vessels throughout the course of the disease.

As the patient ages into the fifth decade, the choroidal vessels change from a reddish-orange color to a yellow-white. The optic disc, retinal vessels and RPE outside the macular area usually appear normal.

|

| 3, 4. Fluorescein angiography (O.D. at 21 seconds left, O.S. at two minutes right) shows a focal area of hyperfluorescence in the macula. |

Variations of CACD include:

Peripapillary choroidal dystrophy. Choroidal atrophy presents in the macula and outward from the optic nerve in all unpredictable directions. Autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive and sporadic inheritance have been reported.

Generalized choroidal dystrophy. Mild to moderate atrophic choroidal vessels appear throughout the fundus. Visual acuity loss occurs later in life. Autosomal dominant and X-linked inheritance have been reported.

Total choroidal vascular atrophy. Choroidal atrophy involves the temporal retina, progresses to the equator and then nasal retinal to equator. The atrophy involves the entire retina to equator by ages 30 to 40. These patients have a poor visual prognosis. This has an autosomal dominant inheritance, with onset at birth.

Visual acuity in patients with CACD gradually deteriorates as the disease progresses. Visual acuity may range from 20/100 to 20/200 in the seventh and eighth decade, but it can be as low as finger-counting.3 There is currently no treatment for this condition.

Ancillary testing is strongly indicated, as CACD often becomes a diagnosis of exclusion. Important tests to perform include:

Fluorescein angiography. Patients with CACD typically exhibit focal areas of hyperfluorescence in the macula due to pigment epithelial atrophy, as in our patient. Importantly, we did not observe a silent choroid, the hallmark of Stargardts disease. As CACD progresses and more atrophy occurs in the macula, loss of the choriocapillaris develops, and the intermediate and larger choroidal vessels can be seen on the fluorescein angiogram.

Electroretinogram (ERG). The full-field ERG can have normal to subnormal values in patients with CACD. Our patient had normal responses in amplitude and implicit time in all rod, mixed and cone ERG. Patients with progressive cone dystrophy will reveal a cone ERG of absent or very low responses. We also performed a multifocal ERG on our patient, which showed centrally reduced responses.

Color vision testing. This simple test can quickly rule in or rule out cone dystrophy, as the color vision will be affected in progressive cone dystrophy and not in the others. Our patient had normal color vision, which helped rule out progressive cone dystrophy.

Visual fields. Patients with CACD usually have a central or paracentral scotoma that corresponds to the macular lesions and will be normal in the periphery. These were findings in our patient.

We educated our patient about the disorder. We told him that he will likely have progressive loss of central vision, but that his peripheral vision will be unaffected and he will not go blind. We encouraged him to have a low vision evaluation.

Retina Quiz Answers: 1) c; 2) a; 3) b; 4) c.

Neha Patel, O.D., an optometric resident at Bascom Palmer Eye Institute in Miami, co-authored this case.

1. Deutman AF. Macular Dystrophies. In Ryan SJ., Ogden TE, Hinton D, et al., eds. Retina. 3rd ed. Volume 2. St. Louis: C.V. Mosby, 2001:1246-9.

2. Yanagihashi S, Nakazawa M, Kurotaki J, et al. Autosomal dominant central areolar choroidal dystrophy and a novel Arg195Leu mutation in the peripherin/RDS gene. Arch Ophthalmol 2003 Oct;121(10):1458-61.

3. Gass JDM. Heredodystrophic Disorders Affecting the Pigment Epithelium and Retina. Stereoscopic Atlas of Macular Disease; Diagnosis and Treatment. 4th ed. St. Louis: C.V. Mosby, 1997:1230-4.