When optometrist Bill F. Hefner, of Topeka, Kan., graduated from optometry school in 1997, he felt fairly confident hed get his foot in the door at a private practice. Why? Because he could offer private practices what many of his fellow graduates could not: a specialty in vision therapy and pediatric optometry.

He was right, as his specialty almost immediately landed him a job at a private practice. Four years later, he became an associate partner at the practice.

Having a specialty in optometry makes you more attractive to potential employers, because you are often in a position to offer a service that a practice does not have already,he says. And, practitioners will therefore want to hire you because they know youll attract a new population of patients.

Optometrist Stephen L. Glasser, of Washington, who specializes in computer vision, adds that specialty practices are crucial to an optom-etrists success. If you do not keep up with your patients needs, they will not be totally satisfied in your ability to handle their problems, and they will go elsewhere, he says.

Whether youre a new grad interested in making yourself more marketable, or youre currently in a pri- vate general practice looking to attract more patients, this two-part article examines how your colleagues have used their specialtiesfive to be exactto make their practices successful. This months installment will discuss the sports vision and computer vision specialties. Additional topics will be covered in next months issue.

Sports Vision Therapy

When Dr. Hefner was initially hired by a full-scope private practice, he expected to focus on pediatric care and vision therapy. But all that changed when he received a phone call from the team trainer of the St. Louis Rams.

Dr. Hefner says that the senior partner of the practice at the time was a friend of the teams sports psychologist. Apparently, the psychologist had told the senior partner that a few members of the team were exhibiting some strange visual behaviors, such as running before the football was actually in their hands.

Dr. Hefner ended up discussing the players problems over the phone with the teams trainer, who then flew him to St. Louis, to give the players eye evaluations. I figured out what the players visual problems were and how these problems were interfering with their performances on the field, Dr. Hefner remembers. From there, I was able to make a few recommendations to the trainer on how they could fix these problems, and they ended up playing better.

He was right, as his specialty almost immediately landed him a job at a private practice. Four years later, he became an associate partner at the practice.

Having a specialty in optometry makes you more attractive to potential employers, because you are often in a position to offer a service that a practice does not have already,he says. And, practitioners will therefore want to hire you because they know youll attract a new population of patients.

Optometrist Stephen L. Glasser, of Washington, who specializes in computer vision, adds that specialty practices are crucial to an optom-etrists success. If you do not keep up with your patients needs, they will not be totally satisfied in your ability to handle their problems, and they will go elsewhere, he says.

Whether youre a new grad interested in making yourself more marketable, or youre currently in a pri- vate general practice looking to attract more patients, this two-part article examines how your colleagues have used their specialtiesfive to be exactto make their practices successful. This months installment will discuss the sports vision and computer vision specialties. Additional topics will be covered in next months issue.

Sports Vision Therapy

When Dr. Hefner was initially hired by a full-scope private practice, he expected to focus on pediatric care and vision therapy. But all that changed when he received a phone call from the team trainer of the St. Louis Rams.

Dr. Hefner says that the senior partner of the practice at the time was a friend of the teams sports psychologist. Apparently, the psychologist had told the senior partner that a few members of the team were exhibiting some strange visual behaviors, such as running before the football was actually in their hands.

Dr. Hefner ended up discussing the players problems over the phone with the teams trainer, who then flew him to St. Louis, to give the players eye evaluations. I figured out what the players visual problems were and how these problems were interfering with their performances on the field, Dr. Hefner remembers. From there, I was able to make a few recommendations to the trainer on how they could fix these problems, and they ended up playing better.

|

|

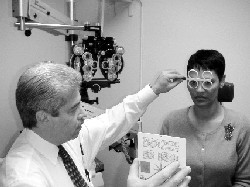

| Dr. Heffner works with a tennis player, emphasizing the importance of following the ball when swinging the racquet. A Marsden ball, a suspended rubber ball used to develop tracking skills, eye-hand coordination and more, was used. |

He says that the experience of working with a professional team excited him enough to pursue the sports vision therapy field. This field involves the evaluation of peripheral vision, static visual acuity, perception, speed and span of recognition and more as they relate to the sport and position the patient holds on a team.

Dr. Hefner, who has been at the same office ever since, has grown the sports vision therapy aspect of the practice through external marketing, which he says has enabled him to market internally and garner referrals. One of the ways he has gotten the sports vision therapy portion of the practice recognized is by arranging a trade for services with the local minor league hockey team.

Dr. Hefner provides the teams primary-care eye needs and provides sports vision therapy to the players, if needed, in exchange for a half-page ad in the teams yearly program, an advertisement on a section of the rink boards, public announcement plugs made during every games intermission and four season tickets.

We periodically give the season tickets to patients who are interested in the sports vision therapy part of the practice, he says. We do this because by going to these games, patients begin thinking, Hey, these guys are pretty good; maybe there is something to sports vision therapy after all. Dr. Hef- ner says this arrangement has been very cost-effective, because the time he spends out of the office with the team is more than made up for with the referrals he gains from the arrangement.

He got his foot in the door with the hockey team by submitting a proposal that highlighted the beneficial services he could provide for the team. Then, he set up a face-to-face meeting with the teams gener-al manager to discuss the proposal. The general manager was very receptive to my proposal, because I didnt ask for money, Dr. Hefner says.

Dr. Hefner, who has been at the same office ever since, has grown the sports vision therapy aspect of the practice through external marketing, which he says has enabled him to market internally and garner referrals. One of the ways he has gotten the sports vision therapy portion of the practice recognized is by arranging a trade for services with the local minor league hockey team.

Dr. Hefner provides the teams primary-care eye needs and provides sports vision therapy to the players, if needed, in exchange for a half-page ad in the teams yearly program, an advertisement on a section of the rink boards, public announcement plugs made during every games intermission and four season tickets.

We periodically give the season tickets to patients who are interested in the sports vision therapy part of the practice, he says. We do this because by going to these games, patients begin thinking, Hey, these guys are pretty good; maybe there is something to sports vision therapy after all. Dr. Hef- ner says this arrangement has been very cost-effective, because the time he spends out of the office with the team is more than made up for with the referrals he gains from the arrangement.

He got his foot in the door with the hockey team by submitting a proposal that highlighted the beneficial services he could provide for the team. Then, he set up a face-to-face meeting with the teams gener-al manager to discuss the proposal. The general manager was very receptive to my proposal, because I didnt ask for money, Dr. Hefner says.

| Consider Sports Vision |

|

Dr. Hefner also has externally marketed the sports vision therapy aspect of the practice by sending out a quarterly newsletter to other eye care practitioners in the area. The newsletter covers patients who have unusual visual problems, whom I have been able to treat either in sports vision or in vision therapy, he explains. I have done this so that these other practitioners are aware of what we do in the event that, say, a 12-year-old baseball player shows up at their office who wants to have a better batting average.

To maintain such referrals, Dr. Hefner sends thank-you letters to the referring practitioners. Each letter he writes:

Dr. Hefner says the practice in which he is an associate partner also sends out patient newsletters to retain and generate referrals. He says the newsletters are sent in the spring and winter, and that they typically include a sports vision enhancement blurb or an article about sports vision based on something that was mentioned in the media. For example, one newsletter included an article about ball-player Mark McGwire when he hit 70 homeruns in 1998. He was not only involved in sports vision enhancement, but also wore specialty contact lenses. Mentioning famous athletes who have used sports vision attracts patients who aspire to be great athletes themselves, Dr. Hefner says.

Dr. Hefner suggests you get involved with sports vision therapy because the field offers O.D.s a refreshing change of pace. Sports vision therapy gets you excited about coming to work again, because it takes you away from routinely spinning the dials and forces you to really think, he says.

To maintain such referrals, Dr. Hefner sends thank-you letters to the referring practitioners. Each letter he writes:

- States that he appreciates the opportunity to participate in the care of the patient.

- Explains what the area of concern for the patient was.

- Details what he did with the patient to alleviate the problem.

- Assures the referring practitioner that the patient has been referred back to his or her care.

Dr. Hefner says the practice in which he is an associate partner also sends out patient newsletters to retain and generate referrals. He says the newsletters are sent in the spring and winter, and that they typically include a sports vision enhancement blurb or an article about sports vision based on something that was mentioned in the media. For example, one newsletter included an article about ball-player Mark McGwire when he hit 70 homeruns in 1998. He was not only involved in sports vision enhancement, but also wore specialty contact lenses. Mentioning famous athletes who have used sports vision attracts patients who aspire to be great athletes themselves, Dr. Hefner says.

Dr. Hefner suggests you get involved with sports vision therapy because the field offers O.D.s a refreshing change of pace. Sports vision therapy gets you excited about coming to work again, because it takes you away from routinely spinning the dials and forces you to really think, he says.

Computer Vision

Dr. Glasser, of Washington, got into computer vision almost 20 years ago, when several of his patients began presenting with problems in near focusing and near vision. He says he traced these problems to his patients work with computers. He then realized that these problems were more widespread because his practice is located in a city that lacks industry and is driven by occupations that require sitting at desks. As a result, Dr. Glasser began doing a lot of research on ergonomics and computer vision.

He has grown the computer vision aspect of his practice by asking his patients very specific questions about computer use and their computer environment, which he believes has instilled patient trust. If you solve a patients problem that has not been solved before or has been missed before by another practitioner or other practitioners, then that patient will sing your praises, which leads to lots of referrals, he says.

|

|

| Dr. Glasser says that in essence, 100% of his practice is devoted to computer vision because of where his practice is located. |

Besides asking specific questions about computer use, Dr. Glasser also provides brochures and handouts regarding the various recommendations he has made and the problems associated with computer use. Because of these two forms of internal marketing, he says his patients have created a buzz about him that has brought about the attention of television and radio stations as well as publications that have been interested in interviewing him. The attention has also led to invitations by various organizations, such as the American Optometric Association, to speak about the vision problems that result from computer use.

| Consider Computer Vision |

|

Dr. Glasser has marketed the computer vision aspect of his practice externally by establishing a practice Web site (www.EyesightInsight.com) and using e-mail to send patients quarterly newsletters, which he says always includes a section on computer vision. If [the patients] dont read the newsletter themselves, they may know of somebody who is having computer-related vision problems, so they can pass it on, he says. Writing up a newsletter is very easy and costs essentially only the time to write it.

Dr. Glasser says that he enjoys dealing with computer vision concerns because they go to the heart of what he feels optometrists do best: prescribing for the visual needs of the patient and providing the care no one else is capable of rendering. (For additional information on computer vision, see CVS: The Specialty You Cant Do Without, July 15, 2004.) Next month, part two of this article will cover childrens vision, low vision and contact lens specialty practices.

Dr. Glasser says that he enjoys dealing with computer vision concerns because they go to the heart of what he feels optometrists do best: prescribing for the visual needs of the patient and providing the care no one else is capable of rendering. (For additional information on computer vision, see CVS: The Specialty You Cant Do Without, July 15, 2004.) Next month, part two of this article will cover childrens vision, low vision and contact lens specialty practices.

Vol. No: 141:11Issue:

11/15/04