|

A 60-year-old man presented complaining of a bilateral, irritated, itchy eyelid and lash area for approximately two months. He had used hot compresses and scrubbed his eyes with baby shampoo, to no avail. He noticed that it began immediately after returning from a trip to Las Vegas and he was wondering if he caught something on the plane.

Examination

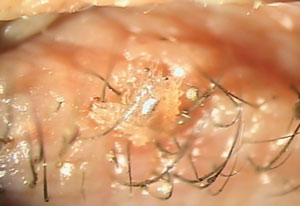

Gross inspection revealed pronounced blepharoconjunctivitis and pruritic lid margin. However, upon closer biomicroscopic examination, what was thought to be lash scaling was actually ruptured and unruptured egg sacks.

Additionally, in the lower lash region, we observed several oval, crab-like organisms clutching onto the cilia with claws. Upon rolling and partially everting the upper eyelids, more live organisms were found. The diagnosis was quite clear: the patient had a crab louse infection.

Lice Infestations

The three major types of lice that infest humans are Pediculus humanus capitis (head louse), Phthirus pubis (crab louse) and Pediculus humanus (body louse).1 Phthirus pubis are the most common mite in eyelid and eyelash infestation. When this occurs, it is termed Phthiriasis palpebrarum. Thus, the more commonly used term, pediculosis, is actually incorrect because this represents infestation with another organism.2-5 Pediculus mites that typically infest the head hair of the patient measure 2mm to 4mm long.

| |

| The louse’s broad, oval, crab-like body features “claws” that firmly grip the patient’s eyelashes. |

Eyelash Infestation

Infestation of the eyelashes is rare and only occurs in the most severe cases. A Phthirus is 2mm long with a broad-shaped, crab-like body. Its thick, clawed legs make it less mobile than the Pediculus species and lend it to infesting areas where the adjacent hairs are within its grasp (eyelashes, beard, chest, axillary region, pubic region). Also, this morphology makes the organism readily identifiable.

Pediculus and Phthirus mites lay eggs on the hair shafts, remaining firmly adherent, resisting both superficial mechanical and chemical removal. Hence, hot compresses and lid scrubs are usually ineffective. Pediculus mites possess good mobility and can pass from person to person either by close contact with an infested individual or by contact with contaminated bedding. Conversely, Phthirus mites are slow-moving organisms that cannot typically pass unless cilia are brought into close proximity with infested cilia, typically through sexual contact. Both species are associated with crowding or poor personal hygiene.1

Ocular signs and symptoms include visible organisms within the eyelashes, visible blue skin lesions (louse bites), reddish brown deposits (louse feces), secondary blepharitis with preauricular adenopathy, follicular conjunctivitis and, in severe cases, marginal keratitis. The patient often presents with ocular itching and irritation. Superinfection of bites can lead to preauricular gland swelling.3-5 The condition may be unilateral or bilateral.

Treatment

Doctors can treat infestations chemically or mechanically.

Topical ophthalmic ointments, such as an antibiotic twice daily for two weeks, can smother the organisms and protect against infection from bites. A steroid-antibiotic ointment can smother the organisms while also providing symptomatic relief, though the extremely minor risk of intraocular pressure elevation may not justify the steroid. Local application of a pediculocide such as yellow mercuric oxide 1% ophthalmic ointment or 0.25% physostigmine (eserine) ointment applied twice daily for a minimum of two weeks will also work.5 Eserine will poison the respiratory system of the organism. Another method for treating Phthiriasis palpebrarum involves a single application of 20% fluorescein. It is nontoxic and non irritating.6 Ongoing treatment is required because the organisms often survive a single application and reinfestation will occur when eggs hatch.

Many advocate mechanical removal of the organisms and eggs.2-8 Doctors can perform this at the biomicroscope with jeweler’s forceps. Be aware that the organism will hold on tenaciously and many lashes may be inadvertently epilated during the procedure. This can be quite uncomfortable for the patient. Application of an ophthalmic ointment can make removal easier in that the organism cannot grasp as tightly to the lashes; however, the ointment may make grasping the organisms themselves more difficult. Once removed, dipping the lice in alcohol will kill them.

Our preference involves mechanically removing all organisms and as many of the eggs as possible, followed by topical antibiotic ointment treatment BID for two weeks.

Beyond the Eyes

When doctors diagnose Phthiriasis palpebrarum, they must also suspect genital involvement. Instruct patients to obtain and use a medicated pediculocidal shampoo. These include, but are not limited to:

- Kwell (lindane 1%, Aspen Pharma)

- Permethrin 1% (Nix cream rinse, Warner-Lambert; Elimite cream, Allergan; Acticin cream, Bertek)

- Pyrethrins/piperonyl butoxide (A-200 Pyrinate, Hogil; Rid, Bayer)

These are safe, effective, nonprescription pediculocides. Due to toxicity, these agents cannot be used on the eyelids. There has been increasing resistance to these pediculocides. An alternate therapy is the oral use of Stromectol (ivermectin 250mg/kg, Merck) for two doses given a week apart to kill the lice and subsequent hatchlings.9,10

Family members, sexual contacts and close companions should be examined and treated appropriately; clothing, linen and personal items should be disinfected with heat of 50 degrees C for 30 minutes.7

Also consider concurrent infection and other sexually transmitted diseases such as HIV, syphilis and chlamydia. Pubic lice infestation is predictive of a concurrent chlamydia infection in adolescents. Adolescents infested with pubic lice should be screened for other STDs, including chlamydia and gonorrhea.11

In children, consider the possibility of sexual abuse and proceed with reporting according to your state law.12 Alternately, contact the child’s pediatrician to share your concern.

For this patient, all of the organisms and egg sacs were painstakingly removed with a jeweler’s forceps and smothered in alcohol. The patient was also prescribed bacitracin ointment to smear onto both eyelids for 10 days.

Clinicians often refer to the unruptured egg sacs as “nits,” while general population uses the term to connote any lice infestation. Physical removal of crab louse and egg sacs (typically with a biomicroscope and forceps) is a tedious and labor-intensive procedure that requires concentration and an exacting eye for detail. Interestingly, this is where the terms “nit-picky” and “nit-picking” come from: to describe a person with an exacting degree of detail and concentration.

In this case, since the patient’s symptoms occurred in conjunction with his trip to Las Vegas, we attempted to elicit a more detailed social history; however, the patient was elusive with his response.

We discussed the likely sexual transmission of this organism and the patient left the exam with the necessary information to make informed social decisions. He never returned for a follow-up.

Drs. Kabat and Sowka have no financial interest in any products mentioned in this article.

1. Ko CJ, Elston DM. Pediculosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50(1):1-12.2. Yoon KC, Park HY, Seo MS, et al. Mechanical treatment of Phthiriasis palpebrarum. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2003;17(1):71-3.

3. Ikeda N, Nomoto H, Hayasaka S, et al. Phthirus pubis infestation of the eyelashes and scalp hairs in a girl. Pediatr Dermatol. 2003;20(4):356-7.

4. Lin YC, Kao SC, Kau HC, et al. Phthiriasis palpebrarum: an unusual blepharoconjunctivitis. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi (Taipei). 2002;65(10):498-500.

5. Yi JW, Li L, Luo da W. Phthiriasis palpebrarum misdiagnosed as allergic blepharoconjunctivitis in a 6-year-old girl. Niger J Clin Pract. 2014;17(4):537-9.

6. Mathew M, D’Souza P, Mehta DK. A new treatment of pthiriasis palpebrarum. Ann Ophthalmol. 1982;14(5):439-41.

7. Keklikci U, Cakmak A, Akpolat N, et al. Phthiriasis palpebrarum in an infant. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2009;46(3):173-4.

8. Couch JM, Green WR, Hirst LW, et al. Diagnosing and treating Phthirus pubis palpebrarum. Surv Ophthalmol. 1982;26(4):219-25.

9. Do-Pham G, Monsel G, Chosidow O. Lice. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2014;33(3):116-8.

10. Burkhart CN, Burkhart CG. Oral ivermectin therapy for phthiriasis palpebrum. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118(1):134-5.

11. Pierzchalski JL, Bretl DA, Matson SC. Phthirus pubis as a predictor for chlamydia infections in adolescents. Sex Transm Dis. 2002; 29(6):331-4.

12. Ryan MF. Phthiriasis palpebrarum infection: a concern for child abuse. J Emerg Med. 2014;46(6):e159-62.