|

A 49-year-old white male presented to the office as a new patient to establish care after moving to the area. He presented with essentially no complaints visually, though he did need an updated pair of glasses.

His medical history was significant for an apparent episode of questionable optic neuritis in the left eye approximately 10 years earlier. At that time, he had complaints of acute visual disturbances in the left eye and, reportedly, several specialists had suspected a differential diagnosis of optic neuritis. He also mentioned that the earlier providers were concerned about the possibility of multiple sclerosis (MS). However, subsequent MR scanning and neurology consult did not firmly establish a diagnosis of MS, and the patient had no other associated symptoms. His vision returned to normal after a few months, and he has since had no visual disturbances. He had maintained good liaison with his eye doctors and neurologists for the subsequent five years, after which time he was seen on a PRN basis.

Diagnostic Data

On initial presentation, the only medication he was taking was naprosyn OTC on a PRN basis, and he reported no allergies to medications. Entering visual acuities through myopic astigmatic correction were 20/30+ OD and 20/25-2 OS. Pupils were ERRLA with no APD. Close attention was paid to the pupillary responses given his history, and no APD was elicited. Best corrected visual acuity was 20/20 OU through increased myopic and astigmatic correction, along with a low add for near reading comfort.

| |

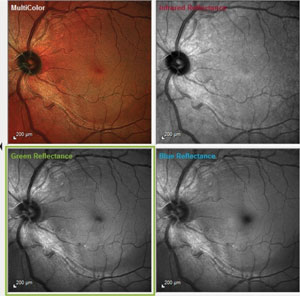

| Fig. 1 These images demonstrate a notable wedge defect along the inferotemporal arcuate fibers, well away from the optic nerve. Also note the loss of nerve fiber robustness in the papillomacular bundle area. |

A slit lamp examination of his anterior segments was essentially unremarkable. Angles were open in both eyes. Applanation tensions were 25mm Hg OD and 26mm Hg OS. Pachymetry readings were 533µm OD and 545µm OS. The patient was dilated in the usual fashion. His crystalline lenses were clear in both eyes. There were some anterior vitreous floaters in each eye and no evidence of PVD in either eye.

His cup-to-disc ratio was 0.5 x 0.55 in both eyes. The sizes of the optic nerves were normal. The temporal rim in the left eye was slightly pale in comparison to the remaining ipsilateral neuroretinal rim, which was plush and well perfused, as was the neuroretinal rim of the right. The pallor was subtle and not distinct enough to label it sectoral atrophy, but considering his history, the clinical findings appeared to match some previous event affecting the left eye. The retinal vascular, macular and peripheral retinal evaluations were entirely normal.

Further Testing

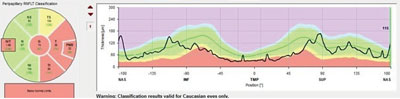

Given the ocular hypertension, we ordered HRT3 (Heidelberg) retinal tomograph imaging and OCT imaging, as well as stereo photography. The HRT3 scan was consistent with the clinical findings on fundoscopy regarding the cup-to-disc ratio and optic disc size. The RNFL circle scan on OCT demonstrated an area of slight thinning inferotemporally in the left eye.

We scheduled the patient for threshold fields and reassessment of IOP after three months, along with gonioscopy. When the patient presented for this visit, one month ago, his IOP was 26mm Hg OU at 11:50am. Threshold visual fields demonstrated paracentral aberrations in both eyes, though the reliability indices were low. Testing showed no obvious evidence of early glaucomatous field defects, nor evidence of central field loss associated with the subtle pallor noted in the left eye. Gonioscopy demonstrated 360 open angles to the ciliary body, with normal trabecular pigmentation and a flat iris approach to the angle.

At this visit I took the opportunity to obtain multi-modal posterior segment imaging using the Spectralis multi-color imaging technology (Heidelberg), as well as run the neurological OCT protocol available on the same technology platform (Figures 1 and 2).

Discussion

This case is representative of clinical situations when the results of our evaluation and testing are not cut and dry. While the patient does indeed have a vague history of some type of visual disturbance in his left eye many years earlier, no definitive diagnosis was made. I am in the process of obtaining old records to see if they can shed light on what happened in the past, but the reality is that we must deal with the situation at this time.

| |

| Fig. 2. Note this is not the traditional TSNIT layout for RNFL scans. Rather, this is an RNFL circle scan beginning and ending nasally, leaving a continuous scan through the papillomacular bundle region. The entire temporal RNFL scan is depressed, consistent with the clinical picture. |

What exactly is that situation? What’s known is that we have a case of ocular hypertension with no definitive optic nerve defects, other than an RNFL scan that shows inferotemporal thinning on a statistical basis. We must be careful in interpreting diagnostic scans, as we tend to heavily rely on normative databases to make diagnoses. We need to remember that normative databases are simply a representation of the statistical findings of the population studied and that the database essentially gives us the typical ‘bell curve’ of data. While the majority of patients will fall into the center of the bell curve, outliers, like this patient, may or may not be normal; the databases simply help identify outliers, not necessarily disease.

This case still raises several questions: What happened to the left eye several years ago? Is the papillomacular bundle thinning visible on multicolor imaging and neuro RNFL scans related to that unknown incident? Is the inferotemporal RNFL thinning related to broad papillomacular bundle defects extending somewhat inferiorly, or is it related to early glaucomatous damage, due to the ocular hypertension? Lastly, is the wedge defect in the inferior arcuate fibers related to glaucoma, neuronal deterioration from another cause, or normal for this particular patient?

Obviously we have more questions than answers. When faced with conflicting clinical data, sometimes the most prudent course of action is to simply monitor the situation and see what changes over time. Certainly, there will be cases and situations when there is immediate intervention is necessary, but in cases such as this, when no acute risk of visual compromise, the best plan of action is to wait and see.

Today’s technology is outstanding, but it still requires a clinician’s interpretation of the information it provides. Using it, we’re able to tailor management plans for particular patients, rather than make global management decisions.

In moving forward with this patient, I chose simply to monitor the patient on a four to six month basis with specific emphasis looking for change in the neuroretinal rim, the RNFL scans and the wedge defect, all from a structural perspective, and changes in the visual fields from a functional perspective.

Slow and steady is the course needed here.