Doc, I feel miserable this morning. I didn’t sleep well at all, my eye is hurting terribly and I’ve been up vomiting half the night.”

|

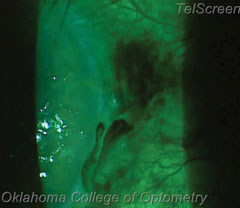

| Any time a postoperative cataract patient presents with an IOP greater than 40mm Hg, we opt to burp the wound by taking a device, which can be seen in this image, and pushing just outside the wound to expel excess aqueous. The bright, almost neon blue in this slit lamp image shows the fluid pulsing around the wound. |

These aren’t really the first words you want coming out of your patients’ mouths the morning after they’ve had cataract surgery. Your first thought should be, “Is my patient having a pressure spike?” While this certainly can be the cause of the pain, other factors, including corneal abrasion, anesthesia effects and, rarely, retrobulbar hemorrhage, may be the causative factor involved. Our clinical experience has shown that it is often the anesthesia wearing off in the hours after cataract surgery, along with the surgery itself, causing significant ocular and periocular pain. If this is the case, the cornea will be intact, IOP will not be elevated, and simple assurance that things will improve in the coming hours is all that is needed, along with possible oral or topical pain relief.

If these other causes of pain, nausea and vomiting are ruled out, and you can confirm that the pressure has elevated significantly, it’s time to consider taking action. Fortunately, you have the proper tools in your toolbox to help them feel better.

During a one-day postoperative cataract visit, obtain the patient’s visual acuity, and perform a thorough slit lamp examination to assess the corneal clarity, conjunctival injection, iris appearance, anterior chamber inflammatory response, lens position and intraocular pressure (IOP).

If you observe a dramatic rise in IOP, you would expect to see some amount of corneal edema. This increase in IOP could be from some remaining viscoelastic in the anterior chamber, inflammation or red blood cells impeding proper drainage of aqueous humor. In other, less frequent, occurrences it may also be associated with a retained lens fragment either in the anterior or posterior chamber.

Depending on how significant the IOP elevation is, a few different approaches can achieve the necessary decrease in pressure. You can use standard topical ophthalmic drops, such as beta-blockers, carbonic anhydrase inhibitors or alpha-agonists. You can also offer oral acetazolamide, if you deem it necessary.

|

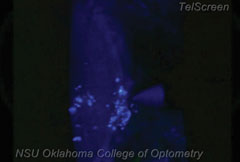

| In our procedure, we employ an 18-gauge needle to burp the wound, although a spud, cotton swab or Weck-Cel sponge may also be used. In this patient’s case, a conjunctival vessel was broken, resulting in the black fluid seen above. Be careful not to confuse this for the fluid you’re attempting to expel, as shown below. As for the nicked conjunctival vessel, the patient can easily blink away the excess blood, as is seen below. |

|

Another option that can show more immediate results is performing a modified paracentesis.

Paracentesis

We say it is “modified” because a paracentesis is typically defined as “a surgical puncture of a bodily cavity with a trocar, aspirator or other instrument usually to draw off an abnormal effusion for diagnostic or therapeutic purposes.”

In our case, a patient was returning for a one-day postoperative examination, so we did not need to recreate the puncture site; the cataract surgeon has already done this for us. The clear corneal incision provides the ideal site to draw off excess aqueous humor contributing to increased IOP. While the clear corneal incision, or the smaller auxiliary port incisions, is considered a self-sealing wound, within 24 hours of the surgery it can be opened easily to provide immediate and dramatic pressure lowering and symptomatic relief to the patient.

We often refer to this as “burping” the wound, since we are not creating a new puncture site.

Indications

Practitioners should consider a wound burp when a patient presents with an IOP approaching 40mm Hg or greater. Consider the procedure especially when patients experience symptoms similar to those of an acute angle closure. These symptoms include pain, headache, nausea or vomiting.1 A significantly hazy cornea with an IOP in the mid 30s or above calls for a wound burp—especially when the aforementioned symptoms are also present.

Another group of patients to strongly consider are currently treated glaucoma patients whose optic nerves already exhibit advanced cupping, and for whom an IOP spike could be detrimental.

Burping The Wound

Prior to a wound burp, perform an examination, including components such as visual acuities, a thorough slit lamp examination and measurements of IOP. Goldmann tonometry is still the standard, and there is really no reason to check the IOP with any other device. Once you’ve completed an exam and obtained an accurate IOP, the steps to burping a wound are as follows:

1. Numb the eye. Instill one or two drops of proparacaine in each eye to improve patient comfort and minimize the blink reflex. If the patient is particularly sensitive, consider an additional drop of Akten (lidocaine gel, Akorn Pharmaceuticals) as well.

2. Administer a topical antibiotic. Instill one drop of an antibiotic, such as moxifloxacin, gatifloxacin or besifloxacin, to reduce the risk of intraocular infection due to the reopening of the wound. The patient will generally be using a topical antibiotic as part of the postoperative regimen.

3. Maximize visualization. Instillation of sodium fluorescein may help practitioners better assess the outflow of aqueous humor from the wound. This is a necessary step, as it will be much more difficult to see the flow of fluid out of the wound in the absence of the fluorescein.

|

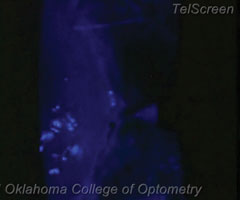

| In this patient’s case, we went in nasally; but more commonly, this procedure is performed by pushing just temporal to the limbus. The illuminated area in this image shows the aqueous fluid about to flow out. |

4. Position the patient. The patient should be aligned comfortably in the slit lamp. Good fixation and head position should be emphasized.

5. Select your instrument. Some practitioners prefer to use a 25-gauge needle to perform a wound burp, though a Weck-Cel sponge, cotton swab or other blunt tool can also be used.

Our clinical experience has shown that an 18-gauge needle is most appropriate for burping the wound. Weck-Cel sponges and cotton swabs, in our experience, tend to be too large when behind the magnification of the slit lamp and can obstruct your view of the wound and the drainage. The fine, small end of a needle seems to accomplish the task much better and are already nicely packaged for sterility.

6. Brace the patient. Have the patient look in the direction opposite from the incision site.

7. Perform the burp. Apply a small amount of pressure just outside of, and perpendicular to, the temporal incision, allowing an opening to the wound that will permit the outflow of aqueous humor. This should appear similar to what one would expect with a positive Seidel sign.

Typically, pressure should be just lateral to the temporal incision site, as that will push the temporal part of the clear corneal incision in and open up the wound.

|

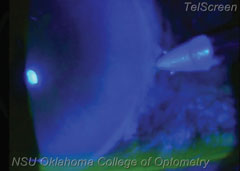

| The surgeon already did the difficult work by providing the side port used for the surgery. To burp the wound, you just push on the outside of that side port, visible in this slit lamp image. |

Our clinical experience has shown that one firm “burp” by the incision for about one second will allow a bolus of fluid to leak out. This tends to lower the IOP by at least 5mm Hg to 10mm Hg, in proportion to the volume of fluid that has been removed. Depending on the practitioner’s comfort level and initial patient IOP, it may require multiple burps to lower the intraocular pressure to an adequate level.

When in doubt, check the IOP again before burping to ensure that the IOP has not gone too low into the single digits. Most IOP’s of 40mm Hg or greater will come down into the teens after just a couple of burps. Burping should never be done too quickly or too firmly.

8. Measure. Repeat IOP measurement to ascertain the amount of reduction in IOP achieved.

9. Burp again. Repeat wound burp until you get the IOP below 20mm Hg.

10. Measure again. Intraocular pressure should be checked again in 60 minutes to ensure that it is not rising significantly. Further treatment with topical or oral therapies, or even a return trip to the OR, may be deemed necessary if there is a rise in IOP at this time.

11. Follow up. Have the patient return in one day to ensure the IOP reduction’s stability. The patient should continue standard postoperative cataract surgery drops.

|

| As you burp the wound, you’ll see the trapped aqueous fluid flow out, through the wound and into the tear lake. It may take several burps—for this patient it took four—but eventually it should lower the IOP. The patient’s pressure in this case was lowered to about 18mm Hg after the procedure. |

Complications

As with any ocular procedure, there are potential complications to educate the patient about. Endophthalmitis is a rare and preventable, but potentially devastating, complication of performing a wound procedure because you are momentarily reopening the eye to the environment. Uncommonly, discomfort or pain during the procedure is possible, as well as bruising or subconjunctival hemorrhage around the site. In patients who have a shallow anterior chambers one should proceed with caution due to the risk of shallowing the chamber further and potentially causing damage to the iris or cornea. The rare patient who has an extremely high IOP and a shallow anterior chamber should be referred back to the surgical center for consultation.

Intraocular pressure spikes are commonly seen by practitioners on follow up the day after cataract surgery. This can be both painful and nauseating for the patient. Having the ability to perform a successful wound burp can bring your patient much faster relief than waiting for traditional topical or oral therapies to take effect. By being able to perform this procedure in office, you save the patient a potentially lengthy trip back to the surgeon, a time-consuming office visit, a delay in treatment and avoid potential medical side effects.

In the end, having an IOP that is lowered quickly helps the patient see and feel better, and is a relief to the doctor as well.

Dr. Ellis is currently completing her residency in optometric management at NSU Oklahoma College of Optometry.

Dr. Lighthizer is the assistant dean for clinical care services, director of continuing education, and chief of both the specialty care clinic and the electrodiagnostics clinic at NSU Oklahoma College of Optometry.

| 1.See JL, Aquino MCD, Chew PT. Angle-Closure Glaucoma. In: Yanoff MD M, Duker MD JS, eds. Ophthalmology. 4th ed: Elsevier, Inc.; 2014. |