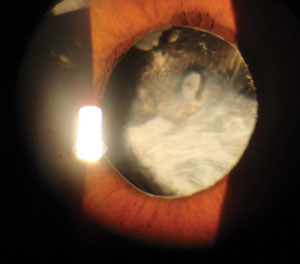

As well-defined, predictable and refined as routine cataract surgery has become, there is one situation in which the surgeon must always plan on surprises and have multiple alternate techniques at the ready: traumatic cataracts. These pose a unique set of problems for surgeons, and even the most thorough slit lamp exam can’t fully prepare surgeons for what they’ll experience in the operating room.

Hope for the Best, Prepare for the Worst

Any amount of injury that causes a traumatic cataract to form will also likely affect collateral tissues. If the eye is stable, the most common associated structural defects would include: iris synechiae, angle recession, iridodialysis, weakened or lost zonular support and lens capsule defects. Careful slit lamp examination will allow you to see much, but not all, of the extent of these defects.

During pre-op evaluation, the surgeon will pay extra attention to any areas that show angle recession or iridodialysis, as this will suggest localized lens zonule defects. The one thing we can’t always see well, or ever confidently guess, is the amount and extent of zonular compromise or posterior capsule integrity. For this reason, any traumatic cataract is approached with a worst-case scenario mindset, and alternative options are planned based on intraoperative findings.

| |

| Surgeons must approach traumatic cataract cases differently than a typical senile cataract—with numerous contingency plans ready, given the potential for intraoperative surprises. |

The surgeon will not know what they are truly dealing with until entering the eye and assessing the structural support of the lens. In almost all circumstances, the surgeon will attempt an extracapsular cataract extraction (leaving the capsular bag intact) and place a new lens in the bag, if possible. When zonules are compromised or missing, the surgeon can use capsular tension rings to maintain the size and circumference of the capsule to allow insertion and centration of a new lens.

Intraoperative Concerns

A significant concern with these cases is the risk of intraoperative vitreous prolapse. When the eye is fully dilated and the lens capsule is manipulated, vitreous may escape anteriorly around the capsule or newly placed IOL, leading to further complications or the need for a vitrectomy. Dispersive viscoelastics, often used to maintain anterior chamber volume, can both keep the capsular bag inflated and tamponade any incipient vitreous prolapse.

If the capsular bag is not suitable for lens insertion, alternative options include: placing the lens in the sulcus (in front of the capsular bag but behind the iris) if there is enough anatomy remaining; suturing a posterior chamber lens to the iris; placing an anterior chamber lens; or leaving the patient aphakic.

Each of these scenarios requires unique lenses, apart from aphakics, that would have to be on hand and preselected based on the patient’s biometry data.

Knowing is Half the BattleBecause of the unknown variables and extensive contingency planning necessary, it is critical to identify these patients before they enter the operating room. A thorough history of all cataract patients should be performed—including always asking about a history of eye trauma. This is especially important for patients of routine cataract age where natural senile lens changes can be hastily assumed. If any history of eye trauma is reported, it should be relayed to the surgeon as early as possible to allow for adequate preparation.