For many children with an ocular disease, early detection and treatment can impact the rest of their life; however, for those who reside in rural and lower-income communities, access to medical professionals trained in these conditions is a challenge. This fact is laid bare in an eye-opening study published yesterday in JAMA Ophthalmology detailing the disparate distribution of pediatric optometrists and ophthalmologists nationwide.

|

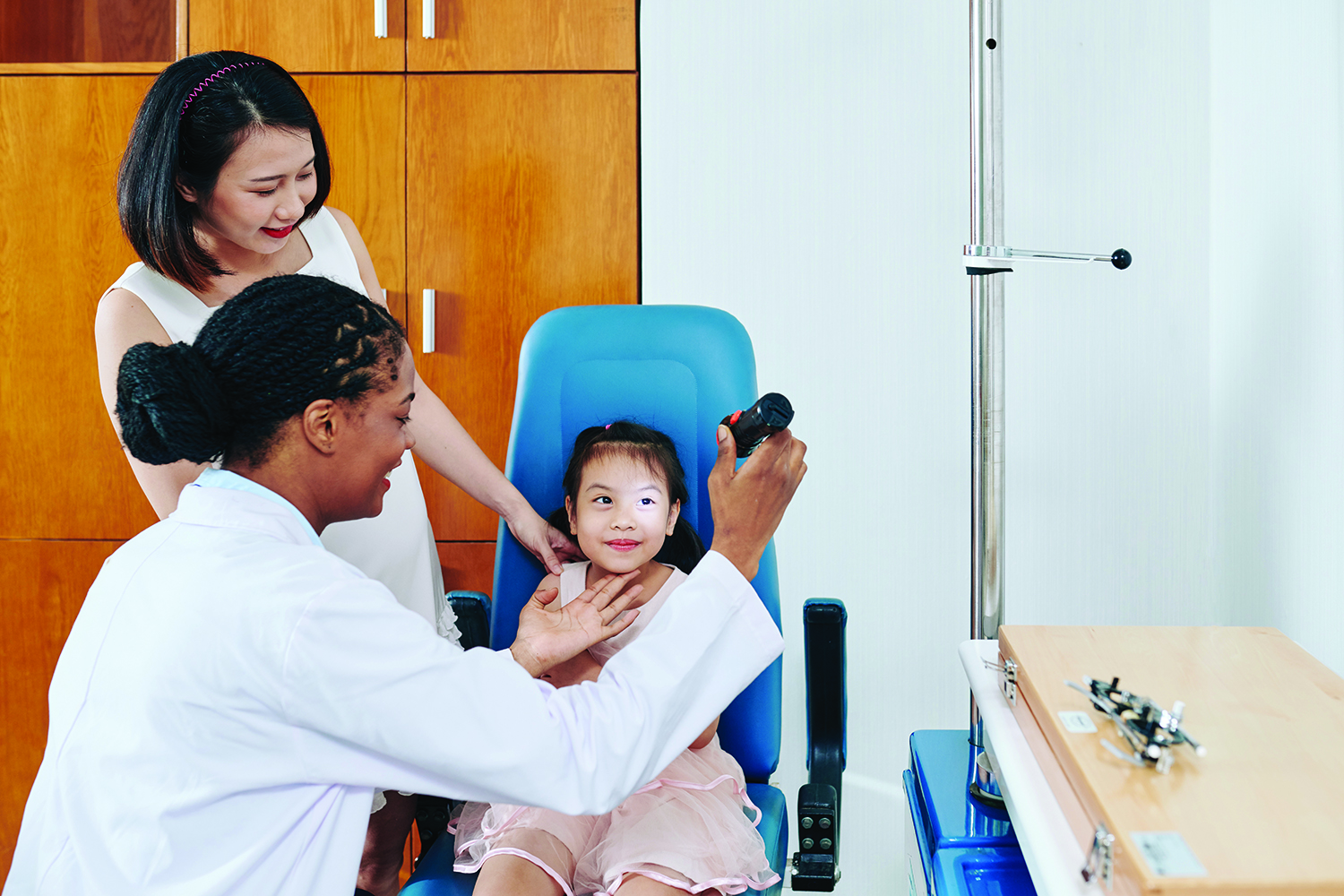

| In a study published in JAMA Ophthalmology, researchers mapped the geographic distribution of pediatric eye care providers in the United States and found the underserved areas were significantly associated with socioeconomic factors, including lower household incomes and a smaller population with bachelor’s degrees. Photo: Getty Images. |

The cross-sectional study performed at the University of Miami identified 586 pediatric optometrists and 1,060 pediatric ophthalmologists in practice in 2023. These numbers are likely to be understated, particularly for optometry. As the profession lacks a formal subspecialization process, the task of identifying pediatric optometrists relies on individual self-reported specialization, an inherently unreliable method. Optometric practitioner quantities were derived from “find a doctor” tools on the websites of the American Optometric Association and American Academy of Optometry. No effort was made to access the College of Optometrists in Vision Development or other potential sources of optometric practitioner info. In a commentary also published in JAMA Ophthalmology, the authors (from UC San Francisco) point out that “the four pediatric optometrists practicing in our institution do not appear listed in either database” used in the study.

With these methodological shortcomings in mind as a caveat, the analysis does nevertheless shed light on the paucity of pediatric eye care in many US regions. Five states had only one pediatric optometrist: Georgia, Idaho, New Mexico, Rhode Island and South Carolina. Washington, D.C. had none. The states with the highest number of pediatric optometrists were Illinois (61), Ohio (34), Texas (33), and California (32). The numbers for pediatric ophthalmologists were significantly higher: California (115), New York (90), Florida (64), Texas (56) and Massachusetts (52). Vermont and Wyoming had two pediatric ophthalmologists each.

When researchers dug down to a county level, they found that of the 2,834 counties without pediatric ophthalmologists, 2,731 (96.4%) also lacked pediatric optometrists. These same counties were found to have lower median household incomes, a smaller population with bachelor’s degrees, lower home internet access and a greater population younger than 19 years than counties that included access to both types of practitioners.

Study authors say these findings are unsurprising, but their research reveals some key differences between demographic characteristics in relation to the geographic distribution of practitioners. “Collectively, results suggest a stronger association between the absence

of pediatric ophthalmologists and lower household income, lower educational status and households without vehicles compared with pediatric optometrists,” they stated. “The median household income, mean population with bachelor’s degrees, and households with vehicles were all higher in counties with pediatric ophthalmologists than counties with pediatric optometrists.” They go on to say that this could be due to the greater likelihood for optometrists to accept Medicaid and that those children may be seen by the pediatric optometrist instead of an ophthalmologist, according to another study conducted in Michigan and Maryland.

And while the study was based on US census data to determine demographics, researchers say that inherently omits certain demographics, including undocumented immigrants and international patients who didn’t participate in the census. “These groups often encounter health care barriers due to insurance, immigration and financial status,” the authors stated. “Consequently, this analysis may have overlooked disparities in access to pediatric eye care, particularly in regions with a high concentration of census nonrespondents.”

They concluded by calling for further research to assess potential differences in visual acuity outcomes between populations with varying access to these pediatric eye care services.1

The commentary article calls these underserved “medical deserts” an emerging public health concern. Along with the barriers to access highlighted in the original paper, the commentary authors state that one must also consider financial accessibility (insurance acceptance and out-of-pocket costs), practice accessibility (wait times, language barriers and cultural competency) and disparities in patient outcomes. “This study highlights the paradox that children living in pediatric eyecare deserts also face other barriers in access to subspecialty eye care, like the ability to travel to receive in-person care or the infrastructure to receive virtual care,” the authors wrote.

They continued, “Children’s immature visual system renders them particularly vulnerable to delays in diagnosis and management, especially if these delays occur during periods of critical development. Delays in care may lead to permanent vision loss, which can affect quality of life, educational achievements, and economic productivity.”

Collaboration between ophthalmologic and optometric pediatric specialists will need to happen in order to meet these needs, they said, as well as other dramatic efforts, such as disrupting the financial models of pediatric care reimbursement, disrupting the educational models of primary care practitioners and pediatric ophthalmology fellowships, and disrupting the historical separation of pediatric eye care practitioners. “Beyond raising public awareness about the roles, competencies, and services of eye care professionals and ensuring an adequate workforce to meet patient needs, it is important to recognize that eye and vision health is the domain of all types of health care practitioners,” the authors concluded.2

1. Siegler NE,Walsh HL, Cavuoto KM. Access to pediatric eye care by practitioner type, geographic distribution, and US population demographics. JAMA Ophthalmol. April 11, 2024. [Epub ahead of print]. 2. Bass O, de Alba Campomanes AG. Mapping the pediatric eye care deserts in the US: A call for action. JAMA Ophthalmol. April 11, 2024. [Epub ahead of print]. |