|

|

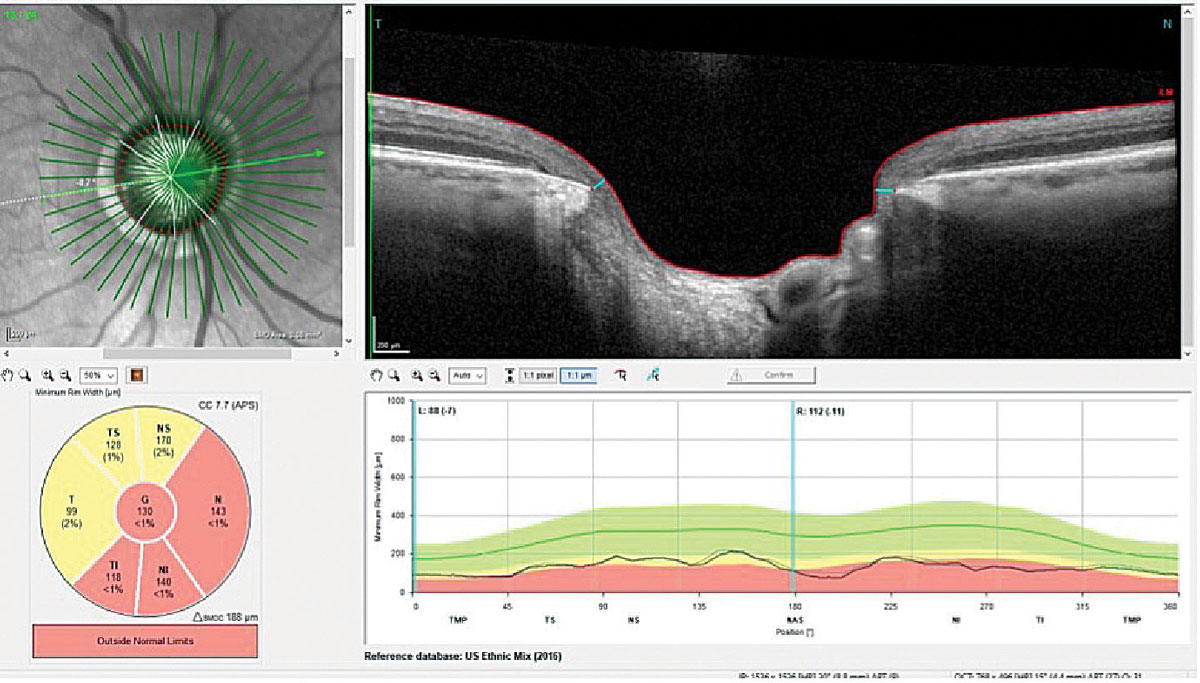

Glaucoma and glaucoma suspects have been identified as much more prevalent in areas of poverty. Photo: James L. Fanelli, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

Social determinants of health, or the conditions in which we are born, grow, live, learn, work and age, can affect a wide range of health outcomes. Six main social determinants of health categories exist: (1) the healthcare system, (2) community and social context, (3) food, (4) education, (5) neighborhood and physical environment, and (6) economic stability. Related to this, research has been conducted to better engage populations most at risk and least likely to have access to eye care to detect and manage glaucoma and other eye disease in community-based settings.

A 2018 CDC effort helped to create an initiative called the Screening and Interventions for Glaucoma and Eye Health Through Telemedicine (SIGHT) network, which is a joint effort by Columbia University, the University of Michigan and University of Alabama at Birmingham. SIGHT investigators, writing in Journal of Glaucoma, described neighborhood-level social risk factors across three study sites in their recent research. The study group also assessed potential characteristics of said populations with intent to help researchers effectively design and implement targeted glaucoma community-based screening and follow-up programs in high-risk groups.

The study included 2,379 participants enrolled in one of the three aforementioned study sites Of all patients, 27% screened positive for glaucoma or being glaucoma suspect. A total of 91% of participants were 40 or older; 64% were female. Demographic-wise, 60% were African American, 32% were white, 19% were Hispanic/Latino, 53% had a high school education or less, 15% had no health insurance and 38% had Medicaid insurance.

The rates of glaucoma and suspected glaucoma were 27% in populations with high levels of poverty and high proportions of those who identify as African American or Hispanic/Latino among targeted glaucoma screenings; this is three times the national average of glaucoma rates. These findings persisted across all three locations which are geographically distinct—spanning rural Alabama, small urban Michigan locations and urban New York City.

Previous research has concluded on two separate occasions that there is an insufficient amount of evidence existing now to assess the balance of benefits and harm of screening for primary open angle glaucoma (POAG) in adults. One challenge that exists is that, even with highly accurate screening, the relatively low rate of POAG in the general population would make screening generate too many false positive referrals—this would strain patients and the healthcare system. As the authors argue, though, this must be weighed against the fact that 50% of those living with glaucoma are undiagnosed.

However, the shifted average of glaucoma prevalence (25%) seen in SIGHT studies decreased the false discovery rate from 79% to 14%, putting much fewer people at risk for overtreatment while simultaneously providing more people to have glaucoma treated a subsequently mitigate vision loss. As such, the study authors believe policy change should address the “how” when directing resources toward communities with high-risk populations who would benefit most from targeted glaucoma screenings.

Looking ahead, they provide these suggestions: “Using community-based engaged research strategies to inform community outreach will likely improve engagement of these medically underserved communities when programs are being implemented. High program satisfaction and consideration of providing low-cost, affordable glasses as part of the eye disease detection programs are also important factors in sustaining community involvement.”

Newman-Casey PA, Hark LA, Lu MC, et al. Social determinants of health and glaucoma screening and detection in the SIGHT studies. J Glaucoma. April 5, 2024. [Epub ahead of print]. |