|

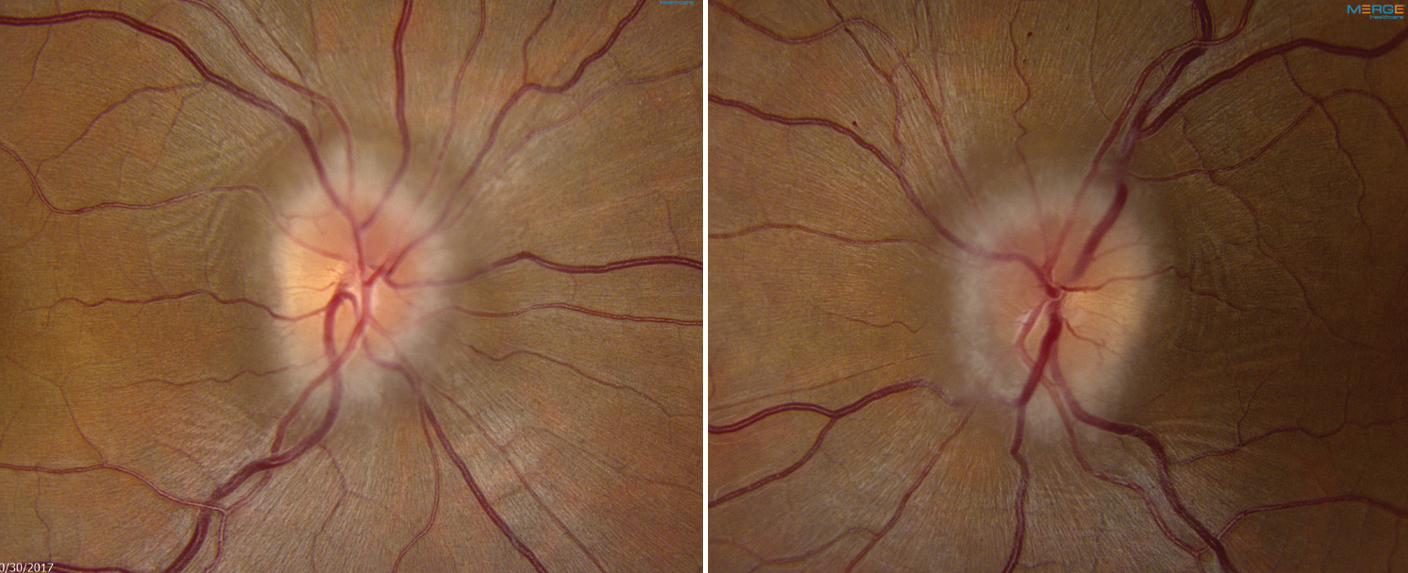

| A case report analysis found that nearly one in five cases of IIH are misdiagnosed, with the proper diagnosis most often being cerebral venous sinus thrombosis. Photo: Mark Dunbar, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

In a new study appearing in Eye, researchers reviewed medical reports to determine how frequent a misdiagnosis of idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) is. The study researchers looked through a decade’s worth of Ovid Medline case reports with patients who were diagnosed with IIH.

Out of a total of 185 case reports, 17.8% were incorrectly labeled as having IIH or the author(s) did not perform all adequate investigations needed to make this diagnosis. Of this percentage, 13.0% of the reports were mislabeled as patients having IIH when they did not, while the other 4.8% did represent ‘probable’ IIH based on clinical presentation but lacked necessary tests to rule out other conditions.

Most commonly, diagnostic criteria weren’t met for the following reasons:

- the physician did not obtain magnetic resonance venography in atypical cases, show evidence of papilledema and/or document the characteristic features seen with neuroimaging

- intracranial hypertension was secondary to another cause

- patients had normal lumbar puncture opening pressure

- the composition of the cerebrospinal fluid was abnormal

The authors also noted that case reports were shown to have a lower journal impact factor if they used the term IIH incorrectly.

For most of the inaccurately diagnosed reports, this study’s researchers were able to place an alternative diagnosis with more accuracy. One of these entities, and the most often found, was cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST). This was missed because the case report authors did not perform the necessary testing to rule out other pathological causes of intracranial pressure, especially in atypical demographics for IIH, like male sex, normal BMI and young children.

The study authors advise that, to confirm IIH “in these cases, it is essential to order magnetic resonance venography, computed tomography venography or contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging to rule out CVST.”

For patients presenting without papilledema, IIH was also commonly misdiagnosed. To qualify as having IIH with papilledema absence, other neuroimaging features must be present, like transverse sinus stenosis, empty sella, posterior globe flattening and optic nerve sheath distension. However, many studies prematurely diagnosed children in this scenario with IIH if they presented with an elevated lumbar puncture CSF opening pressure, even without characteristic neuroimaging findings.

This was done because of the claim that Friedman et al.’s revised criteria overlook prepubertal children with atypical findings. However, the study authors add that “the sole reliance on elevated LPOP to diagnose IIH is misleading, as many intraprocedural factors including Valsalva maneuver and patient positioning can falsely elevate LPOP.”

Finally, IIH was reported in cases that did not present truly ‘idiopathic’ elevated intracranial pressure. The study authors warn that “if elevated intracranial pressure is secondary to the use of medications such as all-trans retinoic acid or antibiotics, then the term ‘idiopathic’ no longer applies.”

They equate this misnomer’s presence to traditional literature likely carrying on the legacy of failing to discriminate between primary and secondary elevated intracranial pressure causes. As a note, the study authors add that IIH can be interchangeably used with ‘primary’ pseudomotor cerebri syndrome, but many cases refer to this without the primary specification, failing to note in this omission the implication of other pathological causes having been ruled out.

The authors conclude with the recommendation that there should be “focused group discussions to identify common knowledge gaps among healthcare practitioners who are responsible for making these diagnoses.”

Eshtiaghi A, Margolin E, Micieli JA. Inaccuracy of idiopathic intracranial hypertension diagnosis in case reports. Eye (Lond). March 16, 2023. [Epub ahead of print]. |