In one new study, researchers examined the morphology of the lamina cribrosa (LC) in school-aged children. Including a total of 120 eyes from 120 patients, 42 full-term kids served as a control group; also included were 41 pre-term kids without retinopathy of prematurity (ROP), 16 kids with ROP treated with intravitreal bevacizumab and 21 kids with ROP treated by laser.

|

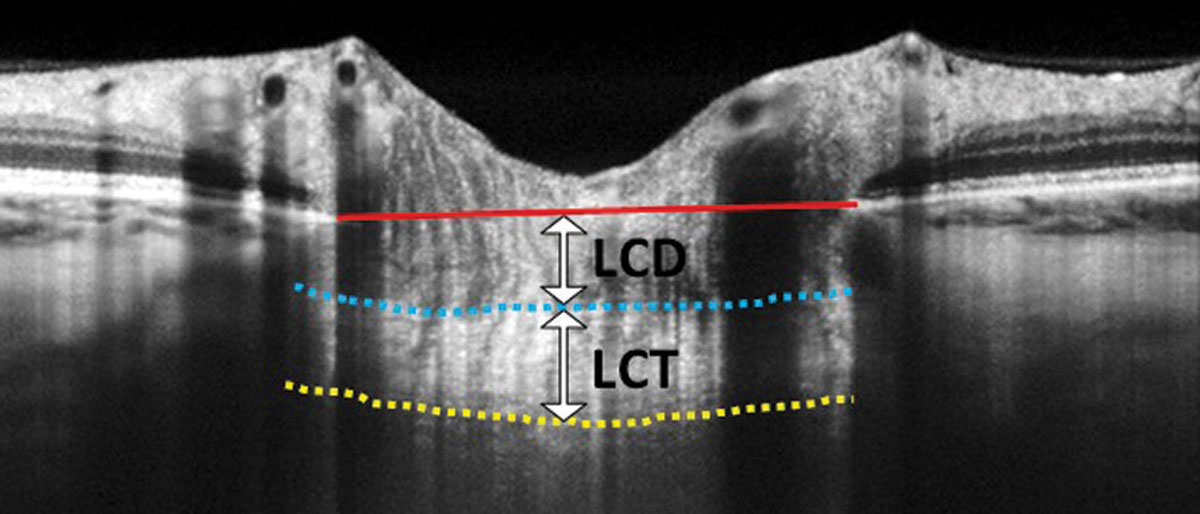

| Pre-term kids, especially ones who have undergone ROP treatment, have a higher degree of myopia compared with those born full-term. Several alterations to the lamina cribrosa were also noted in the study. Photo: Carolyn Majcher, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

Upon looking at OCT parameters, the study researchers found that prelaminar tissue thickness increased with age in both full-term and pre-term children. LC depth and LC curvature index did not display any difference in full-term vs. pre-term children; however, worse refractive errors in pre-term kids were associated with greater minimum rim width and prelaminar tissue thickness. This relationship was not seen in full-term kids. What’s more, those with ROP treated by laser had greater minimum rim width, prelaminar tissue thickness, temporal peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer and foveal thickness than full-term or other pre-term kids.

Consequently, the authors convey that “prematurity and ROP treatment may have an impact on the structural development of the LC. Refractive status plays a vital role in the LC structure of preterm children.”

In the discussion section of their article on the work for the journal Eye, the authors note that the positive association between age and prelaminar tissue thickness in both full- and pre-term kids is an interesting one. Since the prelaminar area is made up of retinal ganglion cell axons and extracellular matrix and is supported structurally by astrocytes, thinning of this area can happen when physical compression occurs or due to retinal ganglion cell axon loss. Thickening with age, however, may indicate that the optic nerve head continues to remodel at school-age.

The laser group of kids with ROP had thicker minimum rim width, prelaminar tissue, peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer and foveal thickness. Premature kids have previously been shown to display inner retinal layer thickening, especially those with laser-treated ROP history. This laser group supported this observation through greater peripapillary retinal nerve fiber layer thickness in the temporal quadrant. As well, the thickened nerve fiber layer entering the optic nerve channel may explain the thicker minimum rim width and prelaminar tissue in this group.

After controlling for confounding factors of gestational age, birth weight, age and choroidal thickness, spherical equivalent refractive error still remained a significant factor for minimum rim width and prelaminar tissue in preterm kids. Evidently, it is important to control refractive error in pre-term children.

In the future, clinicians and researchers should keep in mind that “more attention should be paid to the refractive status of school-aged pre-term children to minimize the impact of refractive errors on the structure of the optic nerve head.”

Lee YS, Kang EYC, Chen HSL, Yeh PH, Wu WC. Comparing the morphology of optic nerve head and lamina cribrosa in full-term and preterm school-aged children. Eye (Lond). April 17, 2024. [Epub ahead of print]. |