|

A 69-year-old white female presented as an emergency exam with a chief complaint of transient visual disturbance. She described these as “blue-colored shadows” that transiently and incompletely blocked the vision of the right eye. She experienced three separate episodes. Each lasted approximately five minutes and was isolated, as she denied symptoms of headache, dizziness, motor weakness, syncope or constitutional symptoms of temporal arteritis.

Upon questioning, she described prior episodes occurring over the past few years, which were attributed to ocular migraine. The remaining ocular history indicated high myopia in each eye. Her medical history was remarkable for essential hypertension and she was taking Bystolic (nebivolo, Forest Laboratories), Norvasc (amlodipine besylate, Pfizer) and triamterene-hydrochlorothiazide. Her family and social histories were unremarkable.

Her best-corrected visual acuity was 20/40 in each eye. Ocular motility was full with no limitation. Pupils were equal, round and reactive to light without afferent defect. Ocular alignment was normal with an orthophoric position in primary and lateral gazes. Additionally, she noted 10/10 color plates in each eye. IOP measured 18mm Hg OD and 19mm Hg OS. The anterior segment exam revealed mild nuclear sclerosis in each eye. Fundus exam showed normal vitreous and retinal structures. The optic nerves showed a cup-to-disc ratio of 0.20 with circumferential chorioretinal atrophy. The neuroretinal rim was pink, healthy, distinct and flat. Digital compression of the globe was negative for retinal-arterial collapse. Subsequently, we ordered a 30-2 threshold visual field test, which showed no localizing features of ocular or neurologic dysfunction.

Diagnosis

In light of the lack of clinical findings, we diagnosed her with isolated transient monocular vision loss (TMVL). The differential diagnoses included amaurosis fugax, impending retinal vascular occlusion and ischemic optic neuropathy, occipital seizure disorder, retinal migraine and acephalgic migraine.

| |

| Fig. 1. MRA of the RICA showing stenosis. |

Because the visual field was unremarkable, symptoms were isolated and digital compression did not reveal arterial collapse, our leading diagnosis was amaurosis fugax. We also considered both forms of migraine as a diagnosis of exclusion. Since she denied symptoms suggestive of cerebral TIA, we alerted her primary care physician and ordered an urgent carotid duplex along with complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), complete metabolic panel (CMP) and lipid panel. The carotid duplex showed severe stenosis of the right internal carotid artery (ICA) and mild stenosis of the left.

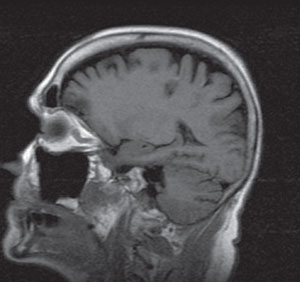

All serology was normal with the exception of moderately elevated lipids. Consequently, we scheduled her for urgent magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) of the neck and brain to detail the location of the stenosis within the carotid artery. We also ordered magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to discount associated cerebral infarction. The MRA showed severe stenosis within the right ICA (Figure 1), along with periventricular white matter (WM) changes and two restricted diffusion foci located within the right posterior parietal-occipital junction, consistent with a subacute infarct.

Causes of WM lesions most commonly include: normal senescent changes, hypertension, focal cerebrovascular accidents, demyelination, migraine, vitamin B6 (pyridoxine) deficiency and infectious or inflammatory-related vasculitis.

Ultimately, we diagnosed her with amaurosis fugax and right hemispheric subacute CVA secondary to severe right ICA stenosis.

Subsequently, she started 81mg of aspirin as prophylaxis and was referred to the vascular surgeon for medical and surgical intervention. The patient immediately started Plavix (clopidogrel bisulfate, Bristol-Myers Squibb) and underwent both a neurologic and cardiovascular work up prior to endarterectomy of the right ICA. She tolerated the procedure well and has been asymptomatic since.

Discussion

Amaurosis fugax is a term used to describe transient monocular vision loss (TMVL) secondary to vascular insufficiency due to atherosclerosis of the ipsilateral internal carotid artery. In 1990, the Amaurosis Fugax Study Group defined five causes of transient monocular blindness: embolic, hemodynamic, ocular, neurologic and idiopathic.1

While most patients with symptoms of amaurosis fugax describe negative visual phenomena (i.e., blurring, fogging, graying or dimming of vision), positive visual symptoms such as colored spots, flashes of light and fortification spectra can also occur, often presenting a challenge to the clinician.2 Differentiating symptoms of benign migraine aura from more ominous causes such as vascular insufficiency or seizure disorders is crucial to timely diagnosis and treatment.

| |

| Two dark lesions within the parietal-occipital region that represent edema from ischemia. |

Migraine aura without headache (acephalgic migraine) is a subset of migrainous phenomena in the adult population. These include symptoms of scintillation, transient hemianopia, central scotomata, classic amaurosis fugax, diplopia, altitudinal field loss, tunnel vision and alterations in color perception.3

Acephalgic migraines typically develop slowly, over 10 to 20 minutes, and rarely occur longer than one hour. While migraine aura is a bilateral phenomenon, many describe the event as unilateral due to obstruction of their nasal field, confounding the diagnosis. The neuronal spread of electrical activity during a migraine coincides with one system being affected at a time in a continuous fashion within the distribution of the cerebral cortex.

Clinicians must also consider the more benign entity of retinal migraine, which often occurs unilaterally and may present in a similar fashion to amaurosis fugax. Retinal migraine, like acephalgic migraine, is a diagnosis of exclusion and should be considered only after discounting other pathologic causes.

Alternatively, seizures typically progress rapidly over the course of seconds, are repetitive and will occur in a single functional neurologic domain involving multiple symptoms simultaneously. Patients experiencing seizure activity are more apt to develop transient syncope and, in some instances, prolonged loss of consciousness.

This case represents an atypical presentation of carotid artery stenosis. It is important to have a low threshold for considering carotid artery stenosis in elderly patients complaining of symptoms masked as migraine aura.

TMVL

Research suggests the annual incidence of TMVL between the ages of 25 and 84 is 13.7/100,000 for men and 9.4/100,000 for women, with the greatest incidence occurring in the seventh decade of life.4 Subsequently, the annual incidence of stroke following TMVL ranges from 2.0% to 2.8%.4

The most common causes of TMVL are ischemia and hypoperfusion, both of which may occur as a result of carotid artery stenosis, carotid or cardiac embolic events or giant cell arteritis. The lack of perfusion pressure causes a brief focal dysfunction followed by a return to normal function. Investigators found that ipsilateral carotid stenosis was responsible for 79% of TMVL symptoms and 57% for less specific complaints such as visual blurring or binocular scintillations.5

With carotid disease, chronic atheromatous plaque formation can result in thrombus formation, increased stenosis, ulceration and occlusion. Clinically, the problem is figuring out who will develop a subsequent cerebral infarct, permanent vision loss or both.

According to an early study, approximately 12% of patients with untreated ocular TIA will suffer a CVA within a year of the onset of symptoms and up to 35% within five years.6 TIAs from carotid stenosis are associated with computed tomography (CT) confirmed ischemic CVA in 15% to 30% of patients. If a patient exhibits symptoms of both ocular and hemispheric TIA, up to 4% are at risk for permanent blindness.6

Diagnostic Testing

Given the risk of developing subsequent CVA, we recommend keeping a low threshold for diagnosis of amaurosis fugax when presented with TMVL. In adult patients with symptoms of acute TMVL without migrainous features, we begin our workup with a complete neuro-ophthalmic history and ophthalmologic exam. We palpate the temporal arteries and assess the neck and trapezius muscles for pain to rule out carotid dissection. If, during a normal exam, the full threshold visual field shows no localization or pattern suggestive of neurologic distress, discuss the case with the primary care physician and order a CMP, ESR, CRP, lipid panel and carotid artery duplex within 24 hours.

Urgent serology allows us to determine the presence of inflammatory disease and comorbid vascular abnormalities. Because of its bimodal properties, the carotid duplex will evaluate the velocity and direction of blood flow, as well as obtain an image of the carotid artery. With a normal duplex and absence of elevated ESR and CRP, we recommend evaluating for blood dyscrasias and obtaining a consultation for a neurologic evaluation. Alternatively, if stenosis is noted on the duplex, the patient should be scheduled for urgent MRA and MRI of the head and neck to obtain better visualization of the carotid artery for surgical intervention and evaluate the soft tissue of the brain for ischemia. In the absence of intracranial pathology, the patient should then be referred to a neurologist for a TIA workup prior to undergoing surgical intervention with a vascular surgeon. Lastly, the patient should undergo a cardiac evaluation, as there is a 33% risk of associated myocardial infarction.7

While patients who experience typical negative visual symptoms of amaurosis fugax have a greater risk of carotid artery stenosis, positive visual phenomena are less diagnostic. Given the findings of severe carotid artery stenosis, ulceration and subacute cerebral infarction, we believe that the positive visual phenomena our patient experienced indicated vascular insufficiency. While she had no complaints of somatosensory or motor weakness, isolated positive visual phenomena are a risk for carotid artery disease, and proper evaluation can reduce the risk of morbidity and mortality.

1. The Amaurosis Fugax Study Group. Current management of amaurosis fugax. Stroke. 1990;21(2):201-8.2. Goodwin JA, Gorelick PB, Helgason CM. Symptoms of amaurosis fugax in atherosclerotic carotid artery disease. Neurology. 1987;37(5):1526-632.

3. O’Connor PS, Tredici TJ. Acephalgic migraine. Fifteen years experience. Ophthalmology. 1981;88(10):999-1003.

4. Andersen CU, Marquardsen J, Mikkelsen B, et al. Amaurosis fugax in a Danish community: a prospective study. Stroke. 1988;19:196–99.

5. Gaul JJ, Marks SJ, Weinberger J. Visual disturbance and carotid artery disease. Stroke. 1986;17:393-8.

6. Lord RSA. Surgery of cerebrovascular disease. St. Louis: Mosby, 1986.

7. Miller NR, Newman NJ, Biousse V, Kerrison JB. Walsh and Hoyt’s Clinical Neuro-Ophthalmology. Baltimore, MD: Williams and Wilkins; 1998.