|

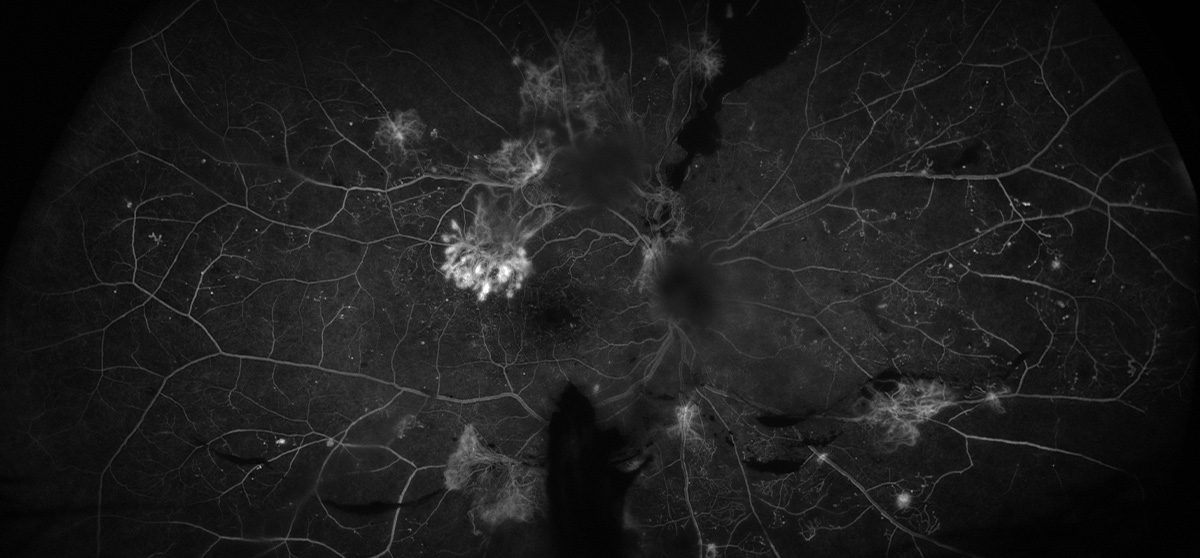

| Glaucoma and diabetes share risk factors of age, ethnicity and hypertension, so patients diagnosed with both conditions may encapsulate a population with more substantial burden of systemic disease, resulting in potential enhanced vulnerability to DR development. Photo: Rami Aboumourad, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

In the largest work of its kind, one new study appearing in Ophthalmology reveals more about the relationship between glaucoma and diabetic eye disease. Specifically, study researchers wanted to assess the correlation between primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) with risk of developing diabetic retinopathy (DR) in both type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus patients.

Included in the retrospective study were 44,359 diabetes patients with POAG and 4,393,300 with no glaucoma, all of which were 18 years of age or older. The primary outcome was first-time occurrence of DR, whether nonproliferative or proliferative, in diabetes patients with and without glaucoma at intervals of one, five and 10 years from their individual index dates.

It was found that at 10 years, both type 1 and type 2 diabetes patients with POAG displayed an increased risk for development of any DR and proliferative DR. At this 10-year mark, the combined association of POAG on DR risk in type 1 and type 2 patients was higher among glaucoma patients at 5.5%, whereas those without glaucoma was 2.1%. Furthermore, cumulative incidence of diabetic retinopathy was higher in the POAG group than in the non-glaucomatous group after a decade.

Put succinctly, the authors convey that their findings suggest those with diabetes and glaucoma are at higher risk of developing first-time DR, whether it be nonproliferative or proliferative, than those with no glaucoma history. This is especially important clinically since this risk remained despite diabetes type and sub-groups analyzed.

Although it has been thought in the past that intraocular pressure (IOP) elevation may protect against DR development, the authors of this study point to several mechanisms that could explain the contradictory associations observed here. One possibility has to do with fluctuations in ocular perfusion pressure, which is linked with elevated IOP, a hallmark of glaucoma. Hemodynamic changes caused by compromised autoregulation of retinal blood flow in glaucoma may subsequently contribute to progression of DR.

The second proposed mechanism may be linked to retinal ganglion cell (RGC) loss. Losing RGCs, which happens with POAG, may exacerbate microvascular retinal changes seen with diabetes because of neurovascular coupling disruption. This disruption results in blood flow alterations signaled from neural activity, which is a critical factor in maintaining retinal health. Consequently disrupting this process, as with POAG, could lead to DR development through imbalance of oxygen supply and demand.

In their paper on the study, the researchers suggest that “clinicians may have to rethink their approach to patients with glaucoma and diabetes to incorporate considerations for DR risk.” They stress the importance of investigating more on mechanistic pathways linking glaucoma and DR. Doing so, they argue, would lead to “a more nuanced understanding of these pathways [which] could potentially inform more targeted therapeutic strategies, allowing for developing treatments that can simultaneously address both conditions.”

They finish with a recommendation for clinicians “to consider more intensive screening and treatment for DR in diabetes mellitus patients diagnosed with glaucoma.”

Chauhan MZ, Elhusseiny AM, Kishor KS, et al. Association of primary open-angle glaucoma with diabetic retinopathy among patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes: a large global database study. Ophthalmology. January 9, 2024. [Epub ahead of print]. |