|

I saw a 92-year-old Caucasian female in June 2021 for a scheduled glaucoma progress evaluation. She was initially seen in 2009 as a new patient with complaints related to slightly decreased vision.

Case

Prior to her first presentation at my clinic, her most recent visit to an eye care provider had occurred about one year earlier, at which point she was told she had cataracts that did not require surgery and to follow-up in one year.

|

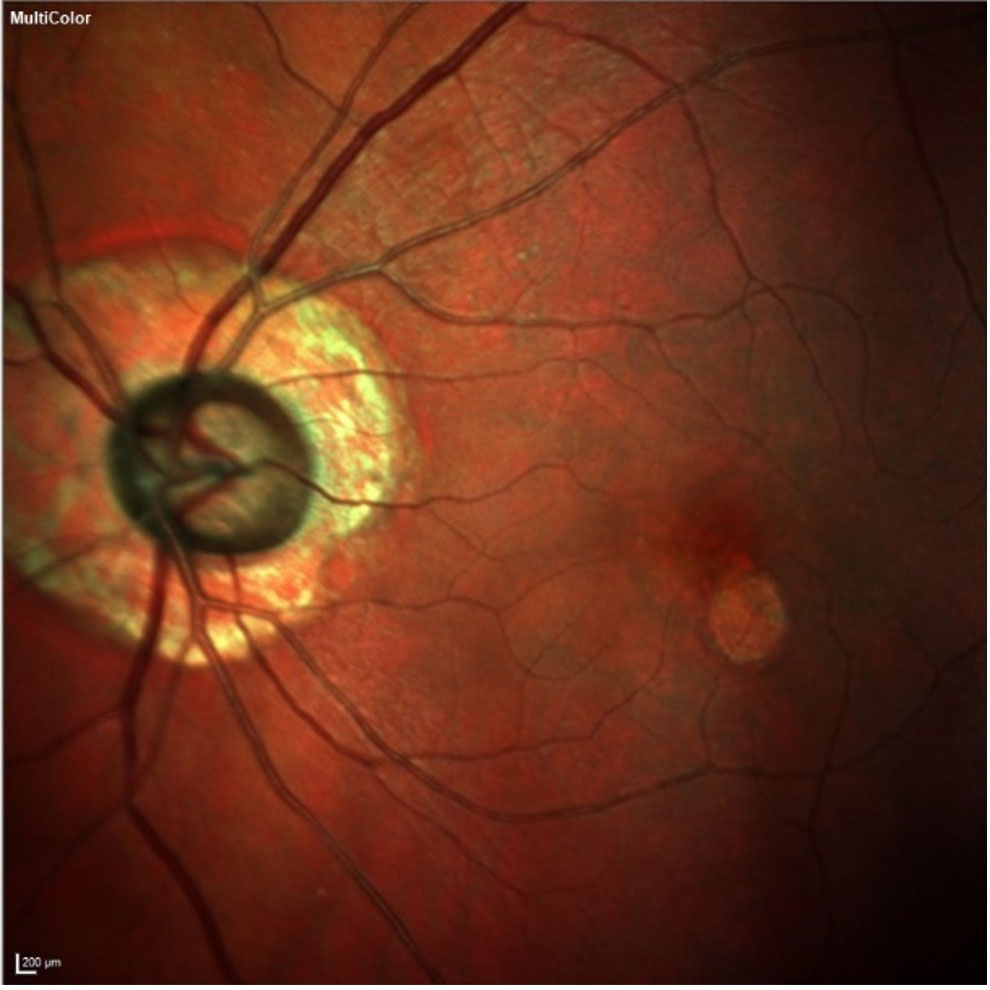

| The patient’s left eye demonstrates advanced neuroretinal rim loss, peripapillary atrophy and macular changes. From an OCT perspective, given the peripapillary atrophy and early macular disease, the neuroretinal rim and Bruch’s membrane opening are the structures where we should look to observe more reliable glaucomatous changes. Click image to enlarge. |

At her initial visit with me, the patient’s entering visual acuities were 20/60 OD and OS, and she was best corrected to 20/40- OD and OS. Pupils were equal, round and reactive to light and accommodation with no afferent pupillary defect, and extraocular muscles were full OU. Her anterior segments were unremarkable with open angles by Van Herick slit lamp estimation.

Through dilated pupils, she was found to have nuclear and cortical cataracts slightly worse OS than OD, along with some macular changes OS>OD consistent with very early macular degeneration. No subretinal abnormalities were found. Her cup to disc ratios were 0.70/0.75 OD and 0.80/0.85 OS with moderate peripapillary atrophy OD>OS, and her optic nerves were judged to be average in size. Her retinal vascular evaluation was consistent with what you would expect to see in an 80-year-old individual, and her peripheral retinal evaluations were normal.

Pachymetry readings were 500µm OD and 483µm OS. Applanation tensions were 15mm Hg OD and 16mm Hg OS. Fundus photos were obtained.

The patient’s initial visit put a potential glaucoma diagnosis OU on my radar, and she was scheduled for a complete glaucoma evaluation including visual fields, gonioscopy and OCT imaging.

The patient complied with my requests for follow-up and was diagnosed with normal-tension glaucoma. Structural damage was confirmed on objective optic nerve and retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) imaging, and bilateral arcuate field defects were found on relatively reliable threshold field studies.

|

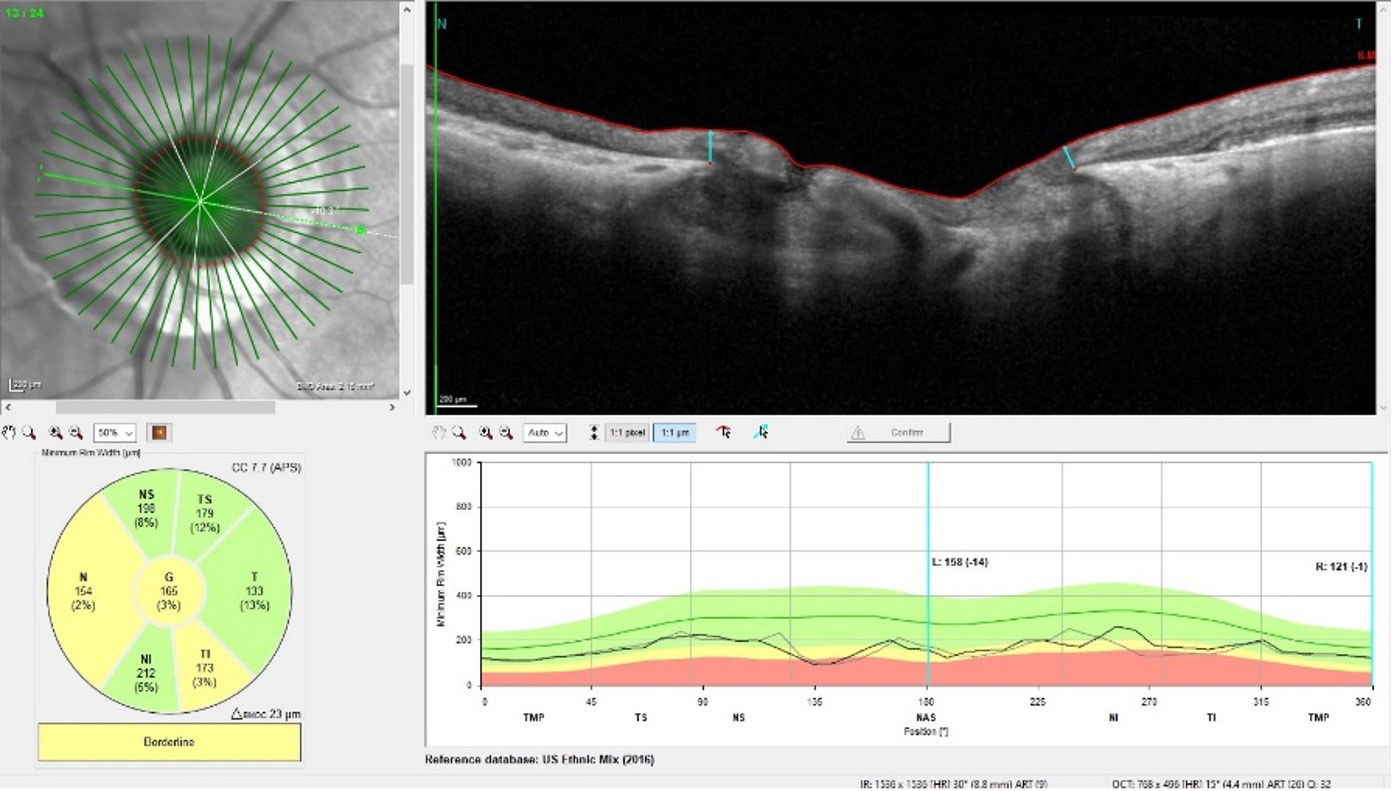

| Note that the circumpapillary RNFL area is affected by the peripapillary atrophy, whereas the neuroretinal rim, showing significant glaucomatous damage, is relatively stable. Click image to enlarge. |

She was started on a prostaglandin 1 drop OU HS and tolerated the medication well. Unfortunately, it did not result in a reliable, consistent lowering of intraocular pressure (IOP), and she was ultimately switched to another medication that she is still using today.

Discussion

Scenarios like this play out in each of our offices regularly. A new patient presents with undiagnosed glaucoma and you make the diagnosis and render appropriate care. Your initial care is geared toward confirming the diagnosis, and subsequent life-long care is focused on keeping the patient visually satisfied and stable throughout their life. Fortunately, for both the patient and the practitioner, we are blessed with a plethora of available instruments, medications, studies and in-office and surgical techniques that can be used to stave off further glaucomatous damage.

In many cases, including this one, the patient will undergo other procedures, such as cataract surgery, that also help preserve vision. With the advent of minimally invasive glaucoma surgery (MIGS) devices, even better outcomes can be achieved.

In this patient’s case, since we were able to achieve adequate IOP control before the development of MIGS devices used in conjunction with lens extraction, her cataract surgery was a straightforward phacoemulsification with standard intraocular lens implantation. Postoperative acuities were good at 20/25 OD and 20/30 OS.

Keep in mind that age-related macular degeneration (AMD) may lurk in the background in cases like this and should be monitored closely. Fortunately, in this patient’s case, her AMD remained mild and non-angiogenic.

|

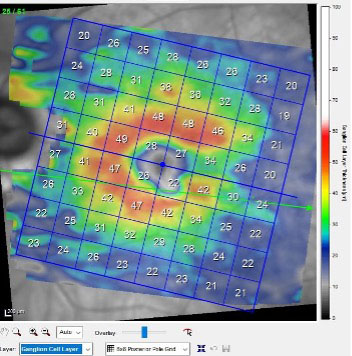

| While the patient’s neuroretinal rim shows significant damage, the macular ganglion cell layer has remained reasonably healthy. Click image to enlarge. |

For nine of the 12 years I’ve cared for this patient, things went rather smoothly. But eventually, that began to change. She seemed to have a shorter temper and attention span, and it became challenging for her to answer relatively simple questions. Not surprisingly, she was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) three years ago, and since then, it had progressed significantly. Up until that point, she had been entirely stable from a glaucoma perspective.

Neurodegenerative disorders such as AD can cause structural changes in the posterior pole when imaged with OCT technology.1,2 RNFL loss, especially in the papillomacular bundle, is perhaps a biomarker of early neurodegeneration.1,3 Optic atrophy has also been reported. Whether AD can worsen glaucoma has not yet been confirmed. But AD can certainly play a role in a patient’s ability to comply with medication schedules. When compliance becomes a problem, often we’ll move toward procedures such as selective laser trabeculoplasty to reduce medication burden and thereby facilitate compliance. AD can also cause patients to forget about appointments. This particular patient’s husband has been wonderful in making sure her prostaglandin is administered OU HS and she never misses an appointment.

When it comes to the shortened attention span that often results from AD, getting through various tests in the office can become burdensome, and test results may be uninterpretable. A good example of this is visual field testing; unfortunately, that was one of the first tests we eliminated from our patient’s office visits.

As AD progresses, in addition to attention span and cognitive issues, physical limitations begin to prohibit detailed evaluation. Even a quick OCT scan becomes a challenge for the patient. These tests are no longer attainable in our patient. We are now down to six-month visits, during which we are able to obtain IOPs using a Perkins tonometer and take a quick look at her fundus and optic nerves.

Given that she has advanced glaucoma, every micron counts from an OCT perspective. But in reality, there is no way to ascertain subtle changes seen on OCT anymore; I can only look for gross changes, and gross changes to her optic nerves will carry a consequent burden of vision loss.

Fortunately, her IOPs, neuroretinal rims and gross vision have all remained stable. What has not remained stable is her neurodegenerative disease. She still lives at home, with outside help concerning some activities of daily living. And though from my perspective her quality of life has changed, I’m not so sure that from her perspective it has changed all that much. But I do know that not changing what our office visits look like insofar as testing and frequency would certainly have had a detrimental effect on her quality of life. It’s all about the patient, and sometimes keeping things simple is the best medicine.

Dr. Fanelli is in private practice in North Carolina and is the founder and director of the Cape Fear Eye Institute in Wilmington, NC. He is chairman of the EyeSki Optometric Conference and the CE in Italy/Europe Conference. He is an adjunct faculty member of PCO, Western U and UAB School of Optometry. He is on advisory boards for Heidelberg Engineering and Glaukos.

1. Chan VTT, Sun Z, Tang S, et al. Spectral-domain OCT measurements in Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ophthalmology. 2019;126(4):497-510. 2. Polo V, Garcia-Martin E, Bambo MP, et al. Reliability and validity of Cirrus and Spectralis optical coherence tomography for detecting retinal atrophy in Alzheimer’s disease. Eye (Lond). 2014;28(6):680-90. 3. Doustar J, Torbati T, Black KL, et al. Optical coherence tomography in Alzheimer’s disease and other neurodegenerative diseases. Front Neurol. 2017;8:701. |