|

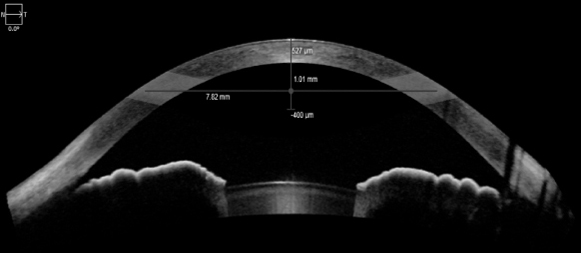

| The cornea—a hormone-responsive tissue—is directly impacted by sex hormone changes in the body, shown in this literature review by the altered corneal features observed in women during menarche, pregnancy and menopause. Photo: Carl Zeiss Meditec. Click image to enlarge. |

Women experience fluctuating sex hormone levels throughout the stages of their life. As a hormone-responsive tissue, the structure and function of the cornea are directly impacted by these changes. The shifting balance of sex hormones in women over time has been shown to affect central corneal thickness (CCT), intraocular pressure (IOP) and tear film quality.

Recently, researchers conducted a systematic review to take a closer look at the corneal changes presenting in women during the three hormonal milestones: menarche, pregnancy and menopause. Literature on the topic was obtained from multiple databases, and 55 articles were ultimately selected for inclusion in the review. The primary outcomes were changes in CCT, IOP, tear break-up time (TBUT), ocular surface disease index (OSDI) and Schirmer’s test by changing levels of female sex hormones associated with the three milestones.

The team identified several studies that present evidence of the effect of sex hormones on CCT at menarche and during the menstrual cycle. One study from Mishra et al. “demonstrated that the central cornea tends to be thinnest at the start of the menstrual cycle (542µm) and thickest at mid-cycle (i.e., during ovulation; 559µm),” the researchers cited in their paper, published in BMC Ophthalmology. Several other studies agreed with this finding, but not all; for instance, Ghahfarokhi et al. found that CCT was greatest at ovulation (556µm) and thinnest at the end of the cycle (536µm), rather than at the beginning of menstruation.

The consensus surrounding the impact of sex hormones on IOP was a bit more straightforward; numerous studies in the review identified higher IOP levels at ovulation vs. at the end of the menstrual cycle (in one study, the difference was 1mm Hg). Like age, race and gender, sex hormones are among the factors that govern IOP level by influencing aqueous production rate, the function of outflow pathways through the trabecular meshwork, related structures and episcleral venous system, as well as corneal curvature and thickness, the researchers explained.

Several discrepancies existed between studies regarding the influence of sex hormone changes on the ocular surface at menarche and during menstruation. For example, Cavdar et al. observed no significant changes in TBUT during the menstrual cycles of 17 premenopausal females, while Versura et al. found a statistically significant difference in tear stability between several phases of menstruation, except in patients with preexisting dry eye disease.

Next, the review authors reported on corneal changes in patients during pregnancy. Most studies noted that CCT increases by an average of 3.1% while IOP decreases by 9.5% between the first and third trimesters.

“Given the presence of estrogen, progesterone, and androgen receptors within corneal epithelial cells, it is plausible that changes in female sex hormone levels could directly lead to changes in CCT,” the researchers noted in their review. Regarding the observed decrease in IOP during pregnancy, they cite one proposed mechanism by Wang et al., which “hypothesizes a relationship between female sex hormones and an increase in aqueous humor outflow capacity, similarly to other body systems where venous capacity expands during pregnancy.” They added, “Peak levels of progesterone, estrogen and relaxin at the end of pregnancy correlate inversely with IOP.”

Hormonal shifts during menopause oppose those during pregnancy (characterized by a drop, rather than an increase, in both estrogen and progesterone); likewise, the corneal changes seen during this milestone are also opposite of those seen during pregnancy. Postmenopausal women typically have decreased CCT and increased IOP levels when compared with premenopausal women.

Postmenopausal women were also shown in numerous studies to have a higher incidence of dry eye disease, worse OSDI scores and worse tear stability than premenopausal women. “The literature suggests inflammation of the lacrimal gland, diminished meibomian gland tissue and reduced lipid production secondary to androgen deficiency as the possible underlying mechanisms,” the researchers wrote in their review.

External hormonal treatments such as hormone replacement therapy were shown to influence corneal features to varying degrees during each of the three hormonal milestones. In some cases, hormonal treatment had a positive effect on the cornea, leading several study authors to consider its potential as a therapeutic intervention. However, the review concluded that it remains inconclusive whether systemic or topical estrogen supplementation benefits ocular surface health.

Based on the current literature, it’s evident that female sex hormones impact corneal structure and function throughout a woman’s life. As the body of knowledge on this subject grows, clinicians can better understand the ocular symptoms women experience as they age, improve risk assessment in surgery planning and use an informed approach to tailor interventions and procedures to patients.

Kelly DS, Sabharwal S, Ramsey DJ, Morkin MI. The effects of female sex hormones on the human cornea across a woman’s life cycle. BMC Ophthalmol. 2023;23:358. |