|

As students—regardless of which optometry school we attended—we all went through similar educational programs. Our earliest semesters involved hours of didactic work, including both classroom and laboratory activities. In the optometric theory and methods sequence at most schools, all of the basic testing procedures are taught in just a few semesters, with refinements to our skills coming as we entered clinical rotations. As we learned so much in such a relatively short time frame, it makes sense that some lesser-used techniques may have been forgotten and are no longer used in our day-to-day practice.

One such procedure is visuoscopy, a quick way to determine whether or not a patient is fixating appropriately with their fovea. The technique can be an invaluable method for evaluating odd or confusing decreases in visual acuity (VA) and, as such, is one that bears reviewing.

Brushing Up

While we often think of visuoscopy as a technique reserved exclusively for doctors who practice vision therapy, it can be useful for any practitioner who wants to assess a patient’s fixation quickly.

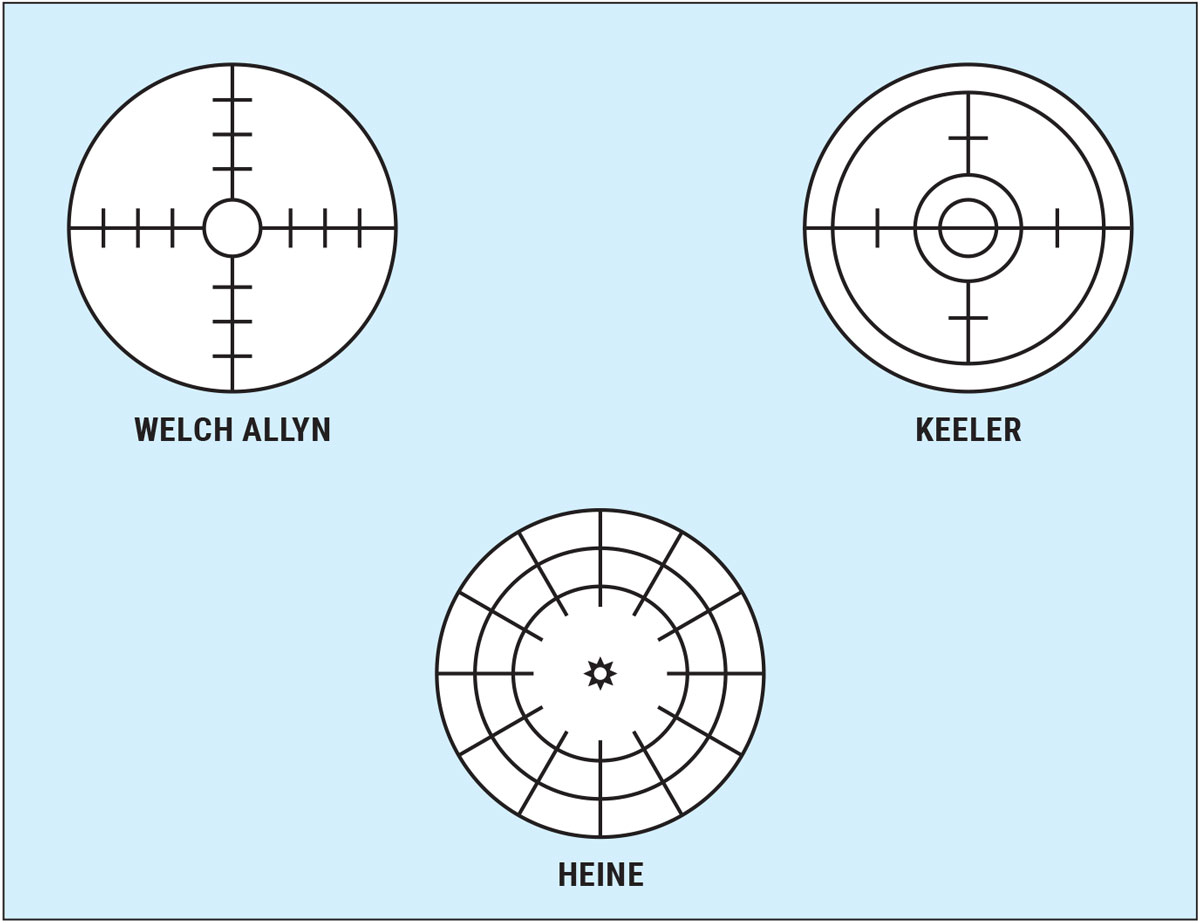

In order to perform visuoscopy, you only need a working direct ophthalmoscope that has a graduated, built-in reticule target; most ophthalmoscopes do. Different brands have different targets, but all are useful for the technique as long as you know how many prism diopters are represented by each of the gradations in your particular instrument. This information can be found online or in the manual that came with your ophthalmoscope—if you still have it! Figure 1 shows the visuoscopy targets from several commercially available directs.

|

|

Fig. 1. Visuoscopy targets from several commercially available direct ophthalmoscopes. Click image to enlarge. |

Visuoscopy can be used to evaluate not only the steadiness (or lack thereof) of a patient’s fixation, but it can also help you to determine whether there is either a microesotropia (defined as an esotropia of between one and 10 prism diopters that has an accompanying foveal suppression) or a small central scotoma present.1-3 Both of these clinical presentations are easy to miss with standard testing procedures, since the small angles in microesotropia are often cosmetically unnoticed and peripheral fusion is usually good. As a result, we can often be left with unexplained decreases in VA.

The procedure itself is simple, but it may require a bit of practice if you don’t routinely perform direct on patients. Not to worry, muscle memory comes back quickly. I (PS) spend the vast majority of my clinic time at Southern College of Optometry in pediatrics and vision therapy, so I have the opportunity to practice the technique on a regular basis—and I’m also one of the strabismus and amblyopia lab instructors at SCO. I know that this makes me biased, but I believe that everyone can learn or refresh this skill with relative ease.

My particular visuoscopy procedure is as follows:

- Have the patient seated comfortably in the exam chair (or standing, as needed for some children) and occlude the eye not being observed/tested.

- Show the patient your visuoscopy target, either on the wall or on your hand, so that they know what they’ll be asked to look for.

- Focus your view on the patient’s optic nerve just as you would for standard direct ophthalmoscopy.

- Once in focus, move over to the patient’s fovea and ask them to fixate the center of your target as steadily as they can. For some targets, the center is a small circle; in others, there is a star for the patient to locate.

- Assess the various attributes of the patient’s fixation and document accordingly.

When we perform visuoscopy, we assess several aspects of the patient’s fixation ability. First and foremost, of course, we need to determine whether the macula is healthy. If there is noticeable pathology present, appropriate follow-up testing should be run. Once we see that the macula and fovea are healthy, we can ask ourselves the other important questions;

- Is the patient fixating centrally? Do they actually use their fovea for fixation, or are they fixating with an eccentric point?

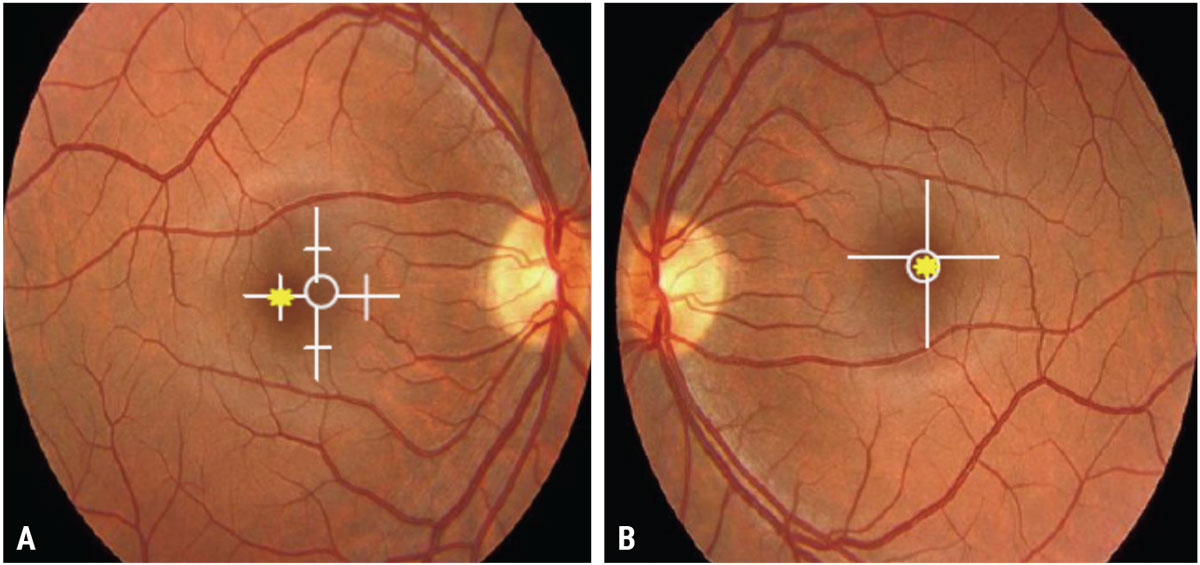

- If the patient is not fixating centrally but is instead exhibiting eccentric fixation (EF), what is the magnitude? How far off of the fovea is their eccentric point, and in what direction does it lie? The magnitude of EF is determined by assessing where on the target the patient’s foveal light reflex appears, relative to the center of your particular visuoscopy target.

The question I pose to my students to help them make this determination is, “What part of the retina is the patient using to fixate instead of their fovea?” This helps them to be able to document superior/inferior, nasal/temporal correctly. Figure 2 shows examples of EF and how they are documented.

- Is the patient’s fixation steady or unsteady? This question is pertinent regardless of whether fixation is central or eccentric. Even when foveal fixation is seen, unsteadiness can cause a mild drop in acuity. (Of course, the steadier a patient’s fixation is, if they happen to show EF the harder it can be to remediate with vision therapy, but that’s another column!)

If you determine that your patient is showing EF, you can predict their best-corrected VA (BCVA) using this formula:

Expected VA = 20/(EF in prism diopters + 1) x 20

For a patient who is showing two prism diopters of EF, this would equal an estimated BCVA of 20/(2 + 1) x 20, or 20/60. Granted, this is an estimate, but it will give you a place to start to determine whether the patient’s drop in VA makes sense.

|

|

Fig. 2. (A) Approximately one prism diopter nasal EF in the right eye; (B) Central fixation (no EF) in the left eye. Click image to enlarge. |

Case

To illustrate how useful visuoscopy can be, I’ll share an example from a recent clinic day. In the summer semester, third-year interns at SCO are taking their Amblyopia & Strabismus course, as well as beginning clinical care. Once we cover visuoscopy in the lab portion, I generally have my interns practice the technique in-clinic when they dilate patients, since it’s much easier to learn through a dilated pupil. As fate would have it, a patient presented who had a BCVA of 20/15 OD but only 20/30-2 OS. Chair skills were all normal. Retinoscopy and refraction were similar, around +0.50 DS in each eye. Anterior segment evaluation showed mild allergic conjunctivitis OU (we do live in Memphis, after all) but was otherwise unremarkable.

No obvious cause could be found for the mild decrease in VA OS, so we dilated the patient and planned a post-DFE retinoscopy to see whether there was additional refractive error in the left eye that might account for the asymmetry. All posterior segment findings appeared negative, but we still didn’t have an explanation for the decrease OS. Call me proud—before I could suggest it, my intern asked, “What about trying visuoscopy?” Sure enough, we saw an unsteady EF of about 0.5PD temporal to the fovea, which lined up perfectly with our expected VA from the formula. Not only was the patient spared additional testing, we were able to send them for a vision therapy evaluation to determine whether their condition could be improved. The student in question, of course, got an A for the day!

Visuoscopy may not be a technique you’ll need often, but it can be invaluable when there’s an unexplained drop in VA. Quick and simple to perform, it not only can provide an explanation but can help guide your management in the best way possible for the patient. Pull out your direct and give it a try!

Dr. Taub is a professor, chief of the Vision Therapy and Rehabilitation service and co-supervisor of the Vision Therapy and Pediatrics residency at Southern College of Optometry (SCO) in Memphis. He specializes in vision therapy, pediatrics and brain injury. Dr. Schnell is an associate professor at SCO and teaches courses on ocular motility and vision therapy. She works in the pediatric and vision therapy clinics and is co-supervisor of the Vision Therapy and Pediatrics residency. Her clinical interests include infant and toddler eye care, vision therapy, visual development and the treatment and management of special populations. They have no financial interests to disclose.

1. Press LJ, Taub MB, Schnell PH eds. Applied concepts in vision therapy 2.0. Optometric Extension Program Foundation. 2021. 2. Griffin JR, Grisham JD. Binocular anomalies: diagnosis and vision therapy. 3rd ed. Butterworth-Heinemann, 1995. 3. Rutstein RP, Daum KM. Anomalies of binocular vision: diagnosis & management. Mosby. 1998. |