|

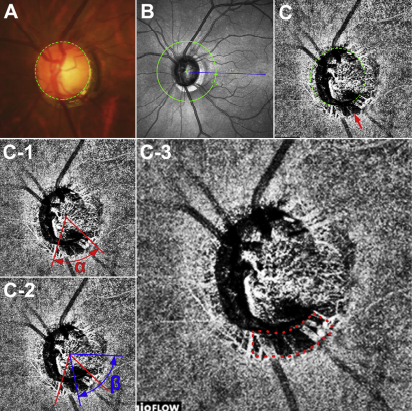

Clinically significant choroidal microvasculature dropout can be observed in areas without a β-zone, suggesting that it and this type of parapapillary atrophy may not necessarily share a common pathogenesis in eyes with POAG. Photo: Vaishaali Gunalan, M. Optom. Click image to enlarge. |

A clinical finding called β-zone parapapillary atrophy has been reported as a risk factor for glaucoma onset and progression. This describes atrophy of the RPE, photoreceptors and choriocapillaris resulting in a distinctive appearance of sclera and choroidal vessels in an area adjacent to the optic disc. Choroidal microvasculature dropout may be an extensive manifestation of β-zone parapapillary atrophy, with the β-zone the microvasculature dropout formation in the choroid. Alternatively, atrophic RPE in the β-zone may simply allow visualization of the choriocapillaris, such that the dropout has been described only in association with β-zone.

Considering the crucial role of this type of parapapillary atrophy and choroidal microvasculature dropout with glaucoma, researchers in South Korea sought to determine the relationship between the pathogenesis of these two. They determined that clinical and optic nerve head structural characteristics potentially relevant to compromised optic nerve head perfusion were dependent on the presence of choroidal microvasculature dropout, rather than the presence of β-zone parapapillary atrophy.

The study included 100 glaucomatous eyes with choroidal microvasculature dropout (25 without and 75 with β-zone parapapillary atrophy) and 97 eyes without choroidal microvasculature dropout (57 without and 40 with β-zone parapapillary atrophy. POAG was defined as the presence of an open iridocorneal angle, signs of glaucomatous optic nerve damage (i.e., neuroretinal rim thinning or notching, or a RNFL defect) and a glaucomatous VF defect.

Regardless of the presence of β-zone parapapillary atrophy, eyes with choroidal microvasculature dropout tended to have a worse visual field at a given RNFL thickness than eyes without choroidal microvasculature dropout, with patients having eyes with choroidal microvasculature dropout having lower diastolic blood pressure and more frequent cold extremities than patients with eyes lacking choroidal microvasculature dropout.

“Peripapillary choroidal thickness was significantly smaller in eyes with than without choroidal microvasculature dropout but was not affected by the presence of β-zone parapapillary atrophy,” the authors wrote in their study. “β-zone parapapillary atrophy without choroidal microvasculature dropout was not associated with vascular variables.”

This finding suggested that β-zone parapapillary atrophy was not a prerequisite for choroidal microvasculature dropout.

“Although the clinical importance of choroidal microvasculature dropout in the absence of β-zone parapapillary atrophy requires long term validation, the presence of choroidal microvasculature dropout, rather than β-zone parapapillary atrophy, should be considered in evaluating the role/relevance of the compromised peripapillary vasculature in glaucoma,” they concluded in their study.

Lee EJ, Song JE, Hwang HS, Kim JA, Lee SH, Kim TW. Choroidal Microvasculature Dropout in the Absence of Parapapillary Atrophy in POAG. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2023;64(3):21. |