|

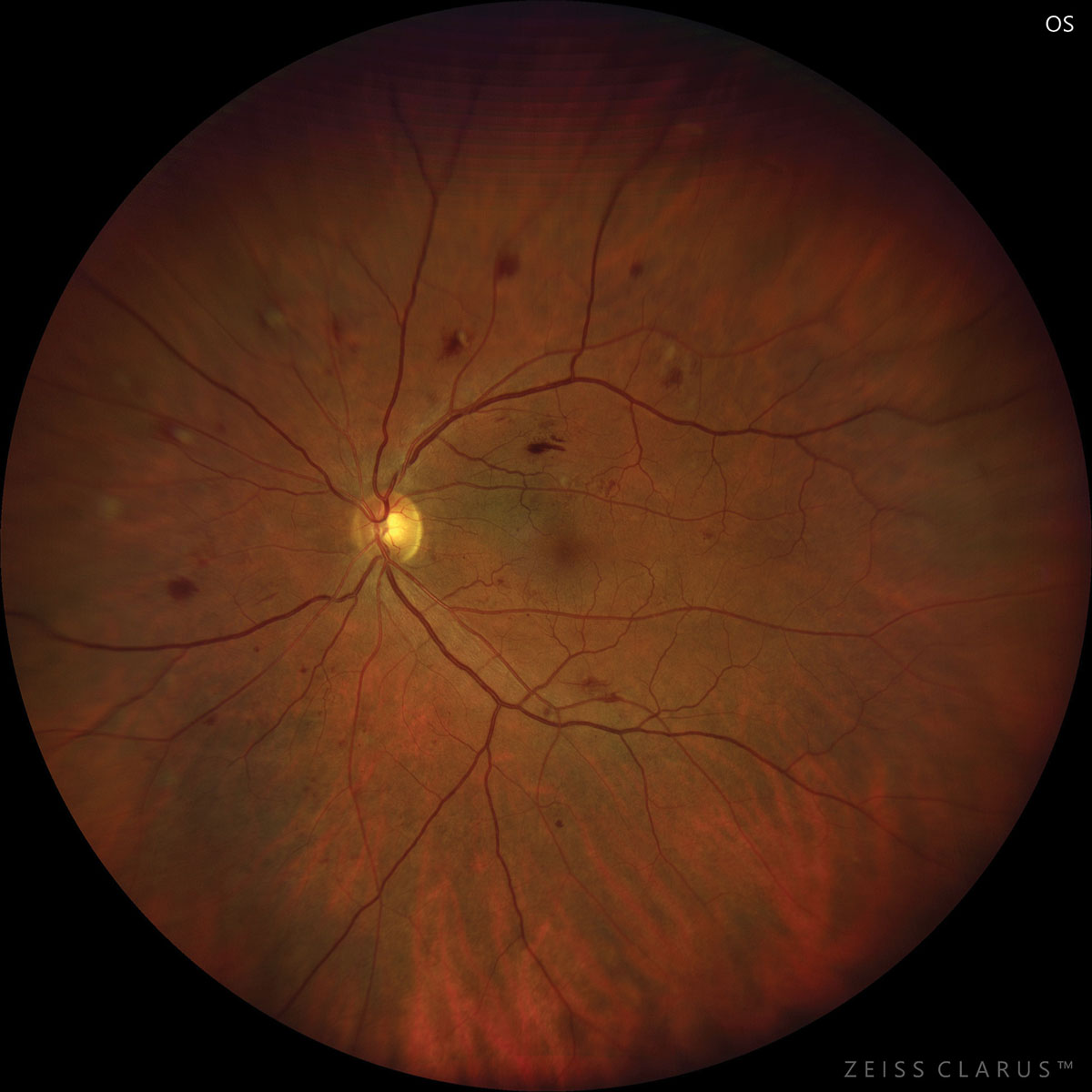

| A current look at data demonstrated that the estimates of DR incidence and progression were lower than those previously reported for American Indian and Alaska Native individuals. Photo: Jay Haynie, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

The Indian Health Service (IHS) is an agency within the US Department of Health and Human Services that provides federal health services to American Indians and Alaska Natives. As it stands, estimates of diabetic retinopathy (DR) incidence in American Indian and Alaska Native patients are not current; instead, they are based on data from before 1992. A recent study, published in JAMA Ophthalmology, confirmed that the estimates of DR incidence and progression were lower than those previously reported for American Indian and Alaska Native individuals. The results of this cohort study have suggested that recent DR incidence and progression among American Indian and Alaska Native individuals served by the IHS are substantially lower than they were 30 or more years ago and are now comparable with estimates from non-American Indian and Alaska Native populations examined in the last 20 years.1

The study analyzed data of 8,374 American Indian and Alaska Native adults with diabetes and no evidence of DR or mild nonproliferative DR (NPDR) evaluated in 2015 and again in 2016 to 2019 by the IHS telehealth program at least one more time. The cohort had a mean age of 53.2 and a mean HbA1c level of 8.3% in 2015, and 57% were female. Patients were evaluated with nonmydriatic ultra-widefield imaging or nonmydriatic fundus photography.

Of the patients with no DR in 2015, 18.0% had mild NPDR or worse in 2016 to 2019, and 0.1% had proliferative DR. The incidence rate from no DR to any DR was 69.6 cases per 1,000 person-years at risk. A total of 6.2% of participants progressed from no DR to moderate NPDR or worse (i.e., 2+ step increase; 24 cases per 1,000 person-years at risk). Of the patients with mild NPDR in 2015, 27.2% progressed to moderate NPDR or worse in 2016 to 2019, and 2.3% progressed to severe NPDR or worse (i.e., 2+ step increase). Incidence and progression were associated with expected risk factors and evaluation with ultra-widefield imaging.

“These low rates support the viability of safely extending the follow-up interval for retinopathy assessment in IHS patients who have no evidence of DR or mild NPDR,” the researchers proposed in their paper. “This may be possible if the IHS patients also have no diabetic macular edema, have minimal risk factors, will be examined with ultra-widefield imaging and their follow-up adherence is not jeopardized.”

Nevertheless, they noted that such a practice change requires examination of adherence to the current recommendations. If a practice change extending the once-per-year follow-up was implemented, further research would be needed to determine if the change affected vision outcomes and adherence rates.1

The team also noted that a more refined measure of hypertension (such as actual blood pressure measurements) may be needed to understand its association with DR changes in this cohort; however, that information is not currently in the program’s database.1 A commentary, also published in JAMA Ophthalmology, noted that “this lack of information can be significant, especially considering the potential impact of not only comorbidities themselves but also the potential resultant lack of compliance with telescreening requirements on disease progression.”2

The author of the commentary did bring up that 39% of the patients who received a baseline evaluation did not complete the follow-up telescreening. Moreover, most patients did not comply with recommended annual retinopathy screening over a span of three years, as only 55% of the patients were documented to have had two or more follow-up examinations.

“Nonadherence to telescreening might be multifactorial and related to both patients themselves and challenges impeding the adoption and implementation of telescreening services in the primary care offices,” the author noted.

Still, she found that the study “highlights the power of new technologies, such as teleophthalmology diabetic screenings, and integration with electronic health records in assessing the disease incidence and progression in a large cohort of patients who represent a racial minority in the United States.”

“The continued advancements in digital health will allow patients to have improved access to care and help the physicians and society better understand the needs of these patient populations,” she wrote in her commentary.2

| 1. Fonda SJ, Bursell S-E, Lewis DG, et al. Incidence and progression of diabetic retinopathy in American Indian and Alaska Native individuals served by the Indian Health Service, 2015-2019. JAMA Ophthalmol. March 9, 2023. [Epub ahead of print]. 2. Rachitskaya A. Use of teleophthalmology to evaluate the incidence and progression of diabetic retinopathy. JAMA Ophthalmol. March 9, 2023. [Epub ahead of print]. |