|

|

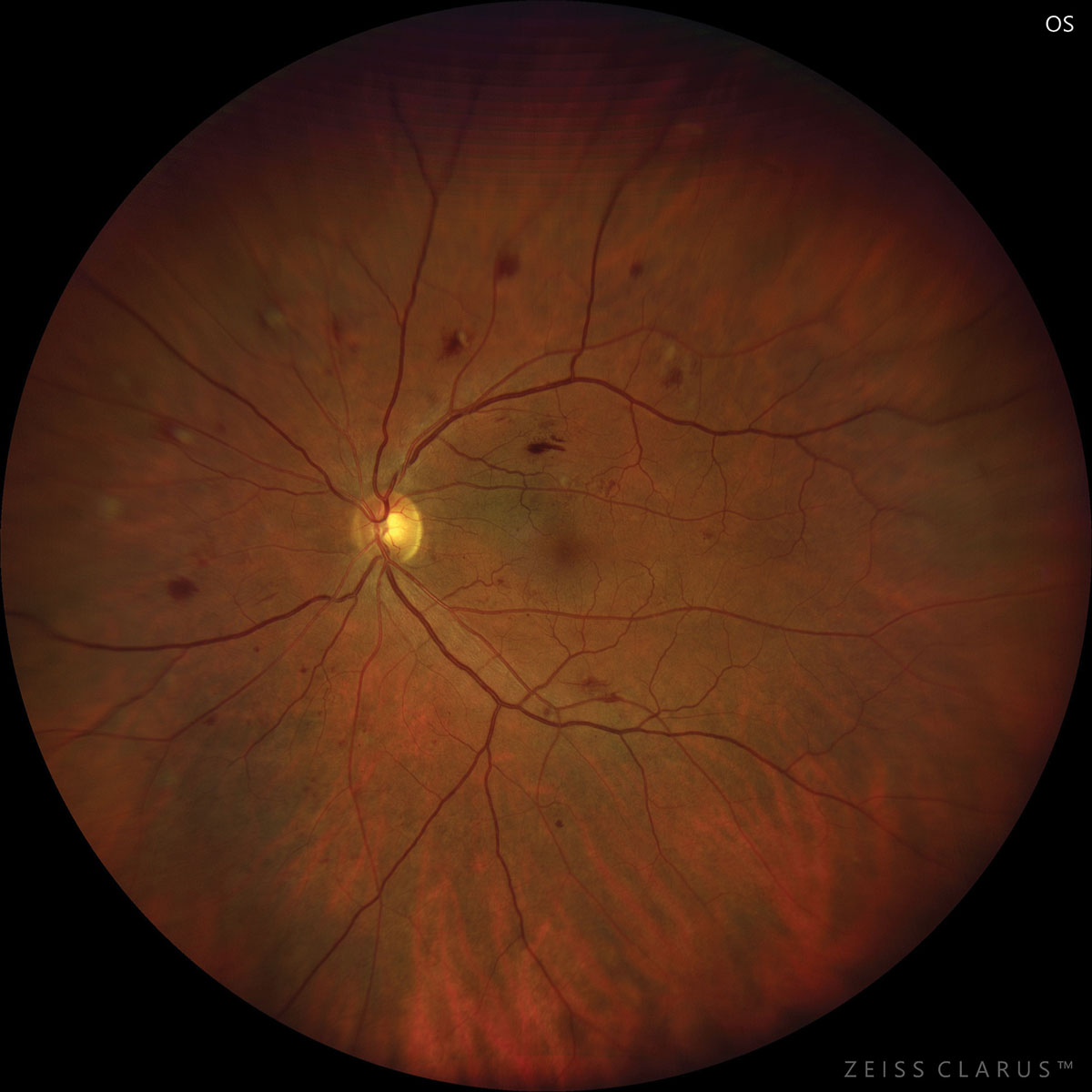

Given no established meaningful visual acuity advantage, this trial does not support earlier treatment for severe nonproliferative DR, at least up to four years. Photo: Julie Torbit, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

The benefits of intravitreal anti-VEGF injections have long been known to eye doctors, particularly in treating patients with AMD and diabetic eye disease. In the latter, it reduces but does not eliminate the risk of vision-threatening complications of diabetes, and it is highly but not 100% effective for these complications once they occur. In a high-profile new study just published in JAMA, early treatment of diabetes-related eye disease slowed progression to severe disease but did not improve visual acuity compared with treating more severe disease once it developed. The study was conducted by the DRCR Retina Network and funded by the National Eye Institute.

DRCR Protocol W aimed to answer the question, “Does prophylactic anti-VEGF treatment in eyes at high risk of vision-threatening complications of diabetes result in better anatomic and vision outcomes at four years when compared with observation with anti-VEGF treatment initiated only after a vision-threatening complication has occurred?” Its two-year primary analysis of this trial showed that aflibercept (2mg every 16 weeks after three monthly loading doses) reduced diabetic retinopathy (DR) severity, lowered the incidence of vision-impairing center-involved diabetic macular edema (DME) and reduced risk of progression to proliferative DR compared with sham. The researchers found that, at four years of treatment, aflibercept as a preventive strategy may not be warranted for patients with nonproliferative DR without center-involved DME.

The study presented four-year primary outcomes of a randomized clinical trial that included 328 patients (399 eyes, mean age: 56), randomized to 2mg aflibercept injections (n=200) or sham injections (n=199). Eight injections were administered at defined intervals through two years, continuing quarterly through four years unless the eye improved to mild nonproliferative DR or better. Aflibercept was given in both groups to treat the development of high-risk DR or center-involved DME with vision loss. Using this strategy, approximately 80% of eyes in the aflibercept group that completed the four-year visit received at least one injection in the fourth year, and approximately 20% needed additional treatment within four years.

Among those receiving aflibercept, proliferative DR or center-involved DME developed in 33.9% vs. 56.9% among those who received sham, a statistically significant difference. The mean change in visual acuity (VA) was -2.7 vs. -2.4 letters, a difference that was not statistically significant.

Four-year DR severity was mild nonproliferative DR or better (DR Severity Scale level ≤35) for 50.4% of eyes in the aflibercept group and 29.3% of eyes in the sham group. From baseline to four years, more eyes in the aflibercept group improved by two or more steps in the DR Severity Scale (54.3% vs. 28.5% in the sham group, adjusted odds ratio: 2.97) and fewer in the aflibercept group worsened by two or more steps (11.0% vs. 22.8% in the sham group).

“The fact that no additional visual acuity benefit was identified with early aflibercept treatment reflects the efficacy of aflibercept once high-risk proliferative DR or center-involved DME with vision loss develops,” the study authors wrote in their paper.

An unanswered question the team proposed is how long eyes that receive early anti-VEGF will need to continue receiving injections to maintain anatomic benefits. “The treatment and visit burden beyond four years is unknown, but a preventive strategy that requires continued injections over multiple years will likely increase the overall treatment burden,” they noted.

“Given no established meaningful visual acuity advantage, this trial does not support earlier treatment for severe nonproliferative DR, at least up to four years,” their study concluded.

“This study indicates that monitoring patients regularly for vision-threatening diabetes complications and treating eyes only as needed is the best approach,” said Raj Maturi, MD, of Indiana University School of Medicine, protocol chair for the study, in a press release from the NEI.

Maturi RK, Glassman AR, Josic K, et al. Four-year visual outcomes in the protocol w randomized trial of intravitreous aflibercept for prevention of vision-threatening complications of diabetic retinopathy. JAMA. 2023;329(5):376-85. |