An 85-year-old woman was brought in by her family for a red right eye. The patient didn’t express herself well verbally because of her age and because she spoke little English, but her family believed that she was having pain as well. When directly asked, she contradicted herself saying that is was painful and then later saying it wasn’t.

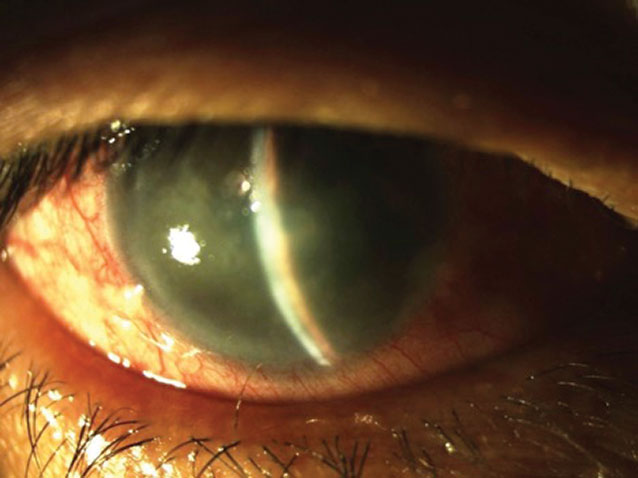

The examination was a bit challenging due to some aging infirmities and generally poor cooperation (likely indicating that she was in pain), but her biomicroscopic examination revealed some rather significant corneal edema and a very shallow anterior chamber, which did not allow for a cell and flare assessment.

Her intraocular pressures (IOP) were 44mm Hg OD and 18mm Hg OS. Gonioscopy was challenging due to her cooperation and corneal edema, but the fleeting views of her right angle showed no structures. The assessment was a bit smoother in her left eye, and only anterior trabecular meshwork could be seen for about half of her angle.

Her current spectacles indicated that she was a +4.50D hyperope in each eye. Considering her refractive error, pronounced symptoms, elevated IOP, shallow chamber and apparent lack of any angle structures on gonioscopy, she was diagnosed with an acute primary angle-closure attack in the right eye.

|

Corneal edema in acute angle-closure attack. Click image to enlarge. |

Discussion

One of the most challenging and visually morbid conditions is primary angle-closure glaucoma (PACG), which can present either acutely or chronically. When acute, the symptomatic nature of the patient requires prompt and accurate intervention. When chronic, it can be overlooked and confused with primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG).

Patients with primary acute angle-closure glaucoma (PAACG) manifest the signs and symptoms of ocular and facial pain, unilateral blurred vision, photopsia in the form of colored haloes around lights and, occasionally, nausea and vomiting. Visual acuity may be reduced significantly in the involved eye, often to 20/80 or worse.1

PAACG is frequently unilateral, but may be bilateral and, as a rule, should always be considered to have bilateral potential, though the timing of the fellow eye involvement may be different.2

Applanation tonometry reveals IOP often in the range of 30mm Hg to 60mm Hg, occasionally higher in some cases.3 Gonioscopy, which may prove difficult because of microcystic corneal edema, reveals no visible angle structures without indentation.

There is a high resistance to forward movement of aqueous through the iris-lens channel due to apposition between the posterior iris and anterior lens capsule, known as relative pupil block. This apposition is most pronounced when the pupil is in the mid-dilated state. In this situation, there is an increased pressure differential between the anterior and posterior chambers, creating a marked bowing forward (convexity) of the iris, termed iris bombé. Angle closure occurs when the peripheral iris physically opposes the trabecular meshwork and impedes aqueous outflow.

In primary pupil block, the tight apposition of the posterior iris to the anterior lens surface in the mid-dilated state must be broken. you must lower the IOP so that the iris can function normally and move from this mid-dilated, pupil-blocking state. Do this quickly, as structural damage to the nerve fiber layer and trabecular meshwork and functional damage to the visual field can occur quickly.4

Management

Primary medication depends upon the pressure at presentation. As most miotics are ineffective at pressures over 40mm Hg due to iris ischemia, initially use aqueous suppressants such as topical beta-blockers, alpha-2 adrenergic agonists and carbonic anhydrase inhibitors.5,6 These medications are typically dosed twice at 30-minute intervals as long as no medical contraindications exist. Prostaglandin analogs will not cause harm, but the medications’ effects may be too slow to be effective in acute situations.7 Also employ an oral carbonic anhydrase inhibitor (two 250mg acetazolamide tablets).

No reliable information exists regarding the efficacy of the topical rho-kinase inhibitor Rhopressa (netarsudil 0.02%, Aerie Pharamceuticals). Rho-kinase inhibitors act mainly to enhance trabecular meshwork outflow, and this structure is physically impeded in PAACG, so this medication should have little or no effect.

Once the IOP is below 40mm Hg, use topical pilocarpine 1% or 2% to miose and reopen the angle. Avoid higher concentrations of pilocarpine, as they can lead to uveal congestion and worsen the condition. A hyperosmotic agent, such as three to five ounces of oral glycerin over ice, may also assist in lowering the IOP and breaking the attack.

It is safe to discontinue acute medical intervention when the IOP falls below 30mm Hg and the angle structures are again visible with gonioscopy. Maintain patients on topical medications as well as oral acetazolamide 500 mg QD-BID until surgical therapy can be obtained.

Surgical Options

Standard treatment for PAACG is laser peripheral iridotomy (LPI) and should be performed as soon as safely possible.6,8 LPI will allow the aqueous fluid pressure to equilibrate between the posterior and anterior chamber, permitting the iris to relax backward with dissipation of iris bombé, allowing aqueous access to trabecular drainage again.

Perform LPI subsequently on any fellow eyes that are potentially occludable. Incisional ocular surgery in the form of trabeculectomy, lens extraction, cyclodestructive procedures, glaucoma implant and goniosynechialysis remain as options for cases unresponsive to medical and laser therapies.9

Trabeculectomy and goniosynechialysis are often combined with cataract extraction. Kahook dual blade-assisted goniosynechialysis and excisional goniotomy at the time of phacoemulsification safely provide significant reductions in both IOP and IOP-lowering medication burden in eyes with angle-closure glaucoma, while simultaneously improving visual acuity.10

After assessing the patient and determining she had no medical contraindications to any glaucoma medications, she was given two drops of Combigan (topical dorzolamide timolol/brimonidine, Allergan), separated by 30 minutes. She was also given two tablets of acetazolamide 250mg PO at the commencement of breaking her attack. A topical carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, Azopt (brinzolamide 1%, Novartis), was also instilled twice over a 30-minute period. After an hour, IOP in the involved eye dropped to 28mm Hg and she appeared to be more comfortable and in less distress.

She was discharged with the topical fixed-combination agent and acetazolamide 500mg sustained release, both to be used twice daily. At follow-up the next day, she was much more comfortable with near complete resolution of her corneal edema and an IOP of 19mm Hg. Subsequent examination was easier to perform and confirmed the diagnosis of an acute angle-closure attack. She was kept on the medications and scheduled for LPI.

1. Congdon NG, Friedman DS. Angle-closure glaucoma: impact, etiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2003;14(2):70-3. 2. Foster PJ. The epidemiology of primary angle closure and associated glaucomatous optic neuropathy. Semin Ophthalmol. 2002;17(2):50-8. 3. Wong JS, Chew PT, Alsagoff Z, et al Clinical course and outcome of primary acute angle-closure glaucoma in Singapore. Singapore Med J. 1997;38(1):16-8. 4. Aung T, Husain R, Gazzard G, et al. Changes in retinal nerve fiber layer thickness after acute primary angle closure. Ophthalmology. 2004;111(8):1475-9. 5. Hoh ST, Aung T, Chew PT. Medical management of angle closure glaucoma. Semin Ophthalmol. 2002;17(2):79-83. 6. Renard JP, Giraud JM, Oubaaz A. Treatment of acute angle-closure glaucoma. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2004;27(6 Pt 2):701-5. 7. Chew PT, Hung PT, Aung T. Efficacy of latanoprost in reducing intraocular pressure in patients with primary angle-closure glaucoma. Surv Ophthalmol. 2002;47 (Suppl 1):S125-8. 8. Saw SM, Gazzard G, Friedman DS. Interventions for angle-closure glaucoma: an evidence-based update. Ophthalmology. 2003;110(10):1869-78. 9. Su WW, Chen PY, Hsiao CH, Chen HS. Primary phacoemulsification and intraocular lens implantation for acute primary angle-closure. PLoS One. 2011;6(5):e20056. Epub 2011 May 24. 10. Dorairaj S, Tam MD, Balasubramani GK. Twelve-month outcomes of excisional goniotomy using the Kahook Dual Blade® in eyes with angle-closure glaucoma. Clin Ophthalmol. 2019; 13: 1779–85. |