As primary eyecare providers, optometrists regularly encounter ocular emergencies that they are well-equipped to handle. While not as frequent, other urgent, non-ocular medical situations can also occur while caring for patients in their clinical practice and it is crucial that ODs are prepared to manage these events properly when they arise.

“As optometric practice has evolved, so has the role of the optometrists,” notes Tad Buckingham, OD, of Pacific University College of Optometry, who recently retired from Forest Grove Fire and Rescue. “We are physicians, and, as such, it is our responsibility to be able to identify and handle medical emergencies when they occur in our clinical practice.”

While optometrists should be prepared to manage or triage numerous medical emergencies, such as anaphylaxis, stroke and seizure to name a few, it can be a step outside of their comfort zone, particularly since these events don’t happen on a daily basis. However, with the right preparation, ODs can feel confident in their ability to contend with non-ocular crises, no matter the situation, says Dr. Buckingham, who uses his experience in emergency services to help educate ODs and other physicians.

This article will discuss common non-ocular emergencies that optometrists may observe in their clinic as well as how to respond appropriately—and quickly—to ensure the best possible care and outcomes for their patients.

|

|

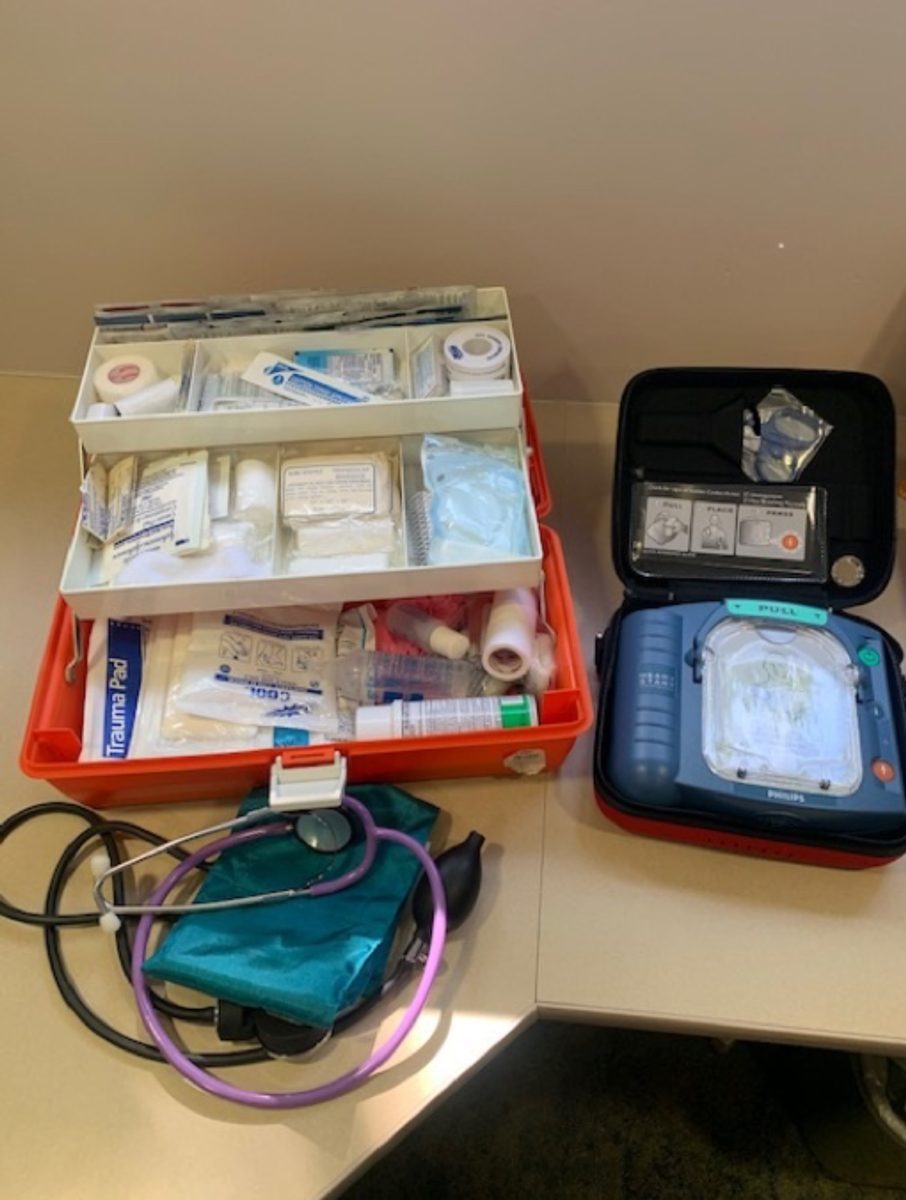

An office emergency preparedness kit may include items such as blood pressure cuffs, first-aid kit and an AED. Place these items in a well-marked location that is easy to access. Photo: Getty Images. Click image to enlarge. |

Identify Common Emergencies

Managing in-office medical dilemmas begins with identification. Optometrists must have the knowledge and skills to recognize these events and take the necessary steps to provide appropriate care.

A medical emergency, Dr. Buckingham explained, can be defined as an intrinsic or extrinsic influence that has acute durational (and not transient) effects on the patient’s:

- Level of consciousness—confusion to unconsciousness

- Respiratory system—airway and breathing

- Cardiovascular system—abnormal/absent pulse and blood pressure

- Disability—body paresis/paralysis, extreme hypo/hyper blood glucose levels

One of the most common non-ocular emergencies optometrists will face is vasovagal response, or fainting, according to Bascom Palmer’s Alison Bozung, OD, who notes that the likelihood of this happening is especially high among patients who need a procedure completed.

“I have seen this occur in patients with corneal foreign bodies, those requiring a corneal culture and even some patients who are extremely squeamish about everting their upper eyelids,” she explains.

Dr. Bozung also emphasizes the importance of recognizing the initial red flags of a syncopal episode. These include the patient getting lightheaded, diaphoretic, dizzy or beginning to slouch back.

“Most times, if we can recognize the signs immediately, we can quickly recline the patient to lower their head and provide something cooling on their forehead,” she continues. “Once in this position and steadied, I will offer a cool glass of water to sip when they can sit more upright again.”

The frequency and type of non-ocular emergencies will vary depending on the size and type of the optometric practice. For Joseph Shovlin, OD, of Scranton, PA, whose main office has 10 providers at one time with over 40 exam rooms, rarely a week goes by without a non-ocular emergency.

“Fortunately, our ambulatory surgical center (ASC) is attached next door, and we have the benefit of a full-time anesthesiologist and nurse anesthetist on hand,” he notes. “Nevertheless, every provider regardless of the size of their practice will at some point in their career be faced with a potentially life-threatening encounter.

“Some life-threatening events encountered in our main facility and surrounding offices included cardiac arrest, drug overdose, seizure, hypoglycemia and anaphylaxis (following fluorescein angiography),” adds Dr. Shovlin. “Other emergencies on a somewhat less troubling order included psychiatric events and asthmatic exacerbations.”

No matter how often optometrists are faced with medical emergencies, it’s critical to be familiar with the specific signs and symptoms of each situation. Proper recognition can allow the OD to act in the most effective way possible, Dr. Bozung emphasizes.

“For example, in patients with anaphylactic reaction, symptoms usually occur within minutes of exposure to an allergen, though they may be delayed up to an hour,” she explains. “The patient may begin to experience difficulty breathing, tightness of the throat, flushed skin or hives, swelling of the face/lips/tongue, a rapid and weak pulse with hypotension.”

In the vast majority of states, according to Dr. Bozung, ODs are legally allowed to administer life-saving anaphylaxis treatment, “and it is certainly something we should be prepared for.”

|

|

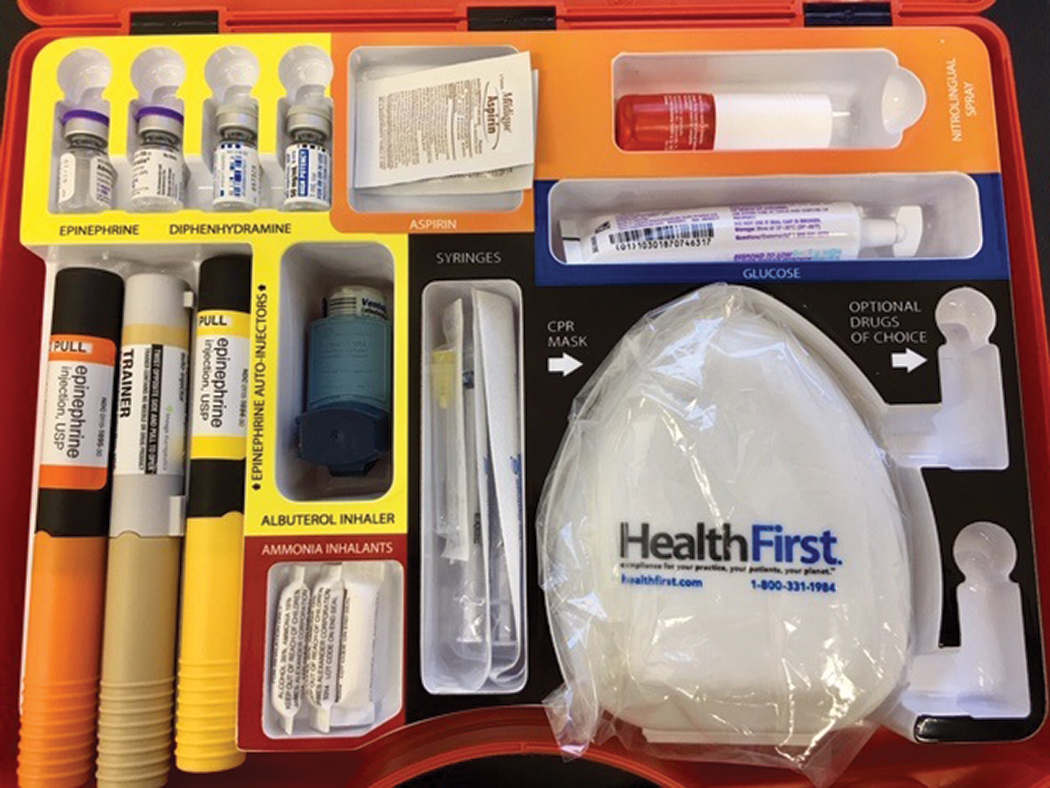

This is the inside of an emergency kit used at Northeastern State University Oklahoma College of Optometry. Photo: Matthew Klein, OD, Sarah Klein, OD, and Richard Mangan, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

• Hypoglycemia—a common and serious side effect of diabetic treatment—can present with a number of symptoms, including trembling, sweating, anxiety, hunger, nausea or tingling as well as neuroglycopenic changes such as confusion, difficulty concentrating, drowsiness, vision changes, dizziness and headache.1

If the patient is conscious, the American Diabetes Association recommends the “15-15” rule—have them consume 15g of a carbohydrate, such as glucose tablets, four ounces (1/2 cup) of juice or regular soda, or one tablespoon of sugar or honey. Then, blood sugar should be checked after 15 minutes. If blood sugar remains below 70mg/dL, this step should be repeated.2 Adjust this for children, as they typically need less than 15g of carbs to fix a low blood glucose level.

Note that no substances should be given to a patient by mouth if they cannot control their airway. These patients will have altered consciousness and not be able to follow directions, Dr. Buckingham notes. “We do not want to make the situation worse by causing aspiration pneumonia.”

“Those who are unconscious require urgent care, and emergency response should be contacted immediately,” according to Chris Kruthoff, OD, who discussed emergency preparedness in a previous Review of Optometry article.

“In these cases, avoid injection of insulin, as it would further reduce blood sugar levels,” he adds. “Do not attempt to provide food, drink or other oral therapies, as these are choking hazards.”1

• Heart attack—Chest pain or discomfort, jaw or neck pain, arm or shoulder pain and shortness of breath are some of the symptoms that could indicate a patient is experiencing a heart attack.1 “One of the most important steps in managing heart attack is getting these patients to a hospital for emergency cardiac care,” says Dr. Kruthoff.

“For patients who are symptomatic for heart attack, call 911 immediately. Give the patient a dose of 325mg aspirin (without enteric coating) to chew for faster systemic absorption and provide water for them to swallow. Monitor the patient until EMTs arrive for transfer to an emergency room with cardiac care.”1

Many medical emergencies may present with ocular symptoms, notes Mohammad Rafieetary, OD, of Germantown, TN. “For example, a patient presenting with sudden-onset vision loss secondary to a retinal artery occlusion may be at risk of cerebrovascular accident or myocardial infarction,” he notes. “This has to be treated as a medical emergency.”

“Consider that a patient with a recent-onset cerebrovascular accident may present with complaints of peripheral vision loss” he adds. “While the patient may have a normal ocular examination, their complaint is neurogenic and has to be managed as a medical emergency.”

Some emergencies may be the result of bodily injury. For instance, an elderly patient, particularly one with some vision loss, may have fallen and hit their head on a hard surface. These patients could present to the OD’s office with concerns about their eyes, but they may have medical issues due to a concussion or cerebral venous sinus thrombosis with or without ocular signs, suggests Dr. Rafieetary, while noting that these situations must be treated as emergencies.

|

|

|

Prepare for the Unexpected

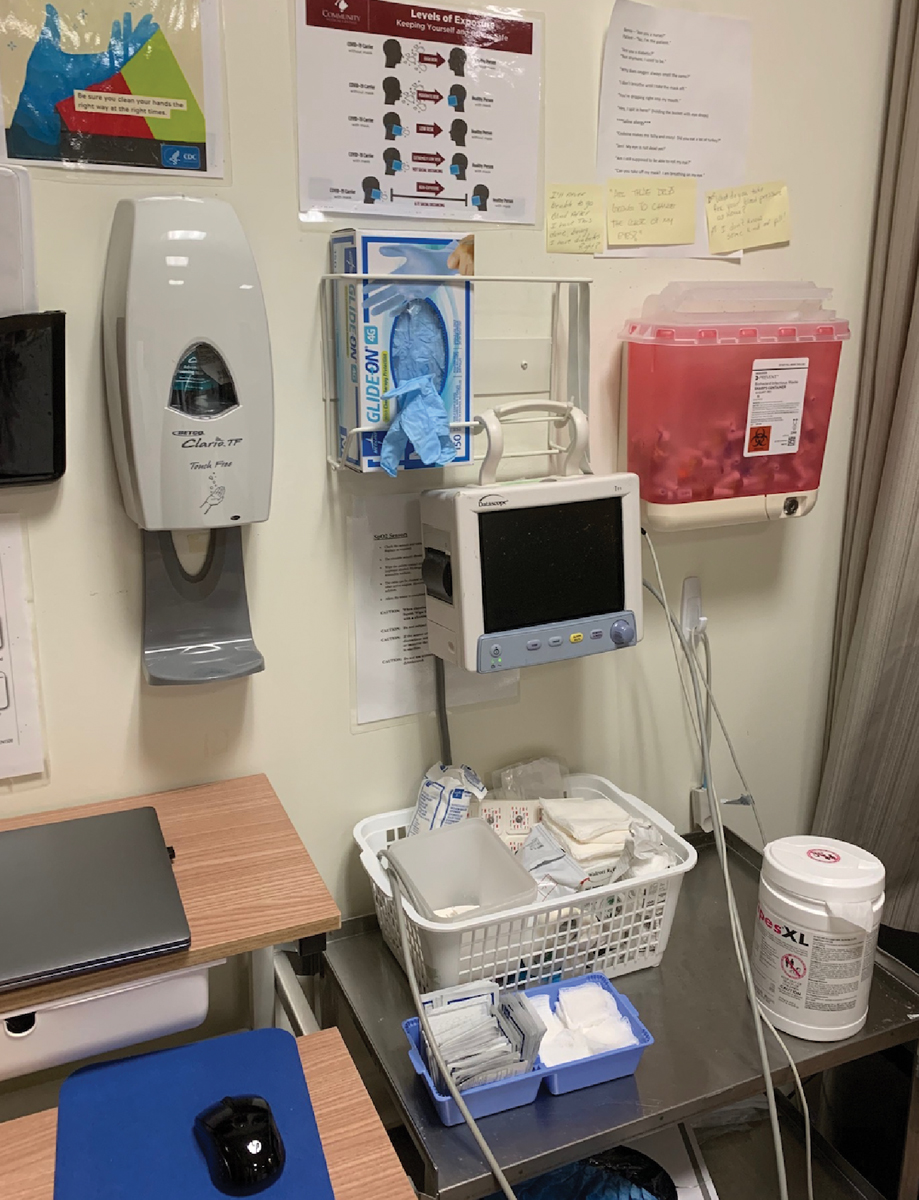

A key component of emergency preparedness is having the right tools on hand—and knowing how to use them. This includes items such as blood pressure cuffs (two sizes), glucose meter, pulse oximeter and universal precautions (latex free gloves, mask, eye protection), according to Dr. Shovlin.

“Having an ASC attached to our main office, we stock bag mask ventilators, intravenous catheter/butterfly needles, intravenous extension tubes, nasal airways, nasogastric tubes, oxygen masks and tanks, portable suction devices, resuscitation tape, resuscitation drugs and more,” he notes. “For ODs who perform multiple surgical procedures (lid procedures included), carrying many of the supplies listed above are essential.”

Danica Marrelli, OD, of the University of Houston College of Optometry, recommends also having these supplies on hand; however, she notes that ODs should check state laws/regulations to see what is and isn’t allowed:

- Glucose tablets or another source of rapidly absorbed glucose (e.g., honey, juice, candy such as Life Savers) to administer if hypoglycemic.

- Non-enteric coated aspirin in case of chest pain.

- Epi-pen in case of anaphylaxis.

- Basic first-aid supplies such as bandages and cold packs in case of orthopedic injury or burn.

Another valuable tool for preparedness is an automatic external defibrillators (AED). The cost is reasonable and the device is easy to use, he says, so all staff should be educated on how to use the device. Supplies and equipment should be portable and kept in one common location.

Depending on where an OD’s practice is located and what state regulations allow, it can be useful to also have Narcan (naloxone hydrochloride, Emergent Bio-Solutions) on hand for drug overdoses and accidental exposures, suggests Dr. Buckingham.

While only some states require it, all optometrists as well as members of their staff should be CPR and BLS certified. The American Red Cross, for example, offers group training courses. This could be beneficial for a small office looking to have more employees certified, suggests Dr. Bozung.

Response times for most emergency agencies are between four and six minutes, notes Dr. Buckingham. “And even with good CPR, people can start losing brain function permanently in about five or six minutes. And so, we can’t depend on the emergency services to be there first,” he says. “We need to be the first ones to identify and start treatment at our training level.

“We’re not trying to be advanced cardiac life support, but we can definitely start CPR and get AED on the patient to help mitigate further harm,” Dr. Buckingham continues. “We have a responsibility to provide care and intervention that is within our skillset and scope of practice.”

Basic first aid and emergency preparedness courses can be valuable, notes Dr. Marrelli. Good recommendations for office preparedness, including staff training and drills, are often found in family medicine, pediatric and dental literature.

A clear action plan is critical for responding to urgent situations, and these plans and policies should be revisited periodically. You never know when it might strike, so you must be prepared at all times, advises Dr. Shovlin, while noting that the OD is responsible for the appropriate handling of any emergency that arises.

“Having your staff ready for action is essential,” he says. “It starts at the front desk, alerting the OD if a patient is ill when they arrive and monitoring any waiting room activity. When an emergency arises, task someone with making the initial 911 call and directing medical personnel to the location in the office when they arrive.”

The size of the practice’s staff will likely determine your exact plan of action. “Depending on staff size, you may be the only renderer of care,” says Dr. Shovlin. “Your only staff member is calling 911. Act quickly and remember: the ABCs: ‘airway, breathing and circulation.’”

|

|

A crash cart can store life-saving equipment in the event of a crisis. Photo: Joseph P. Shovlin, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

“Staff response to these situations makes a great topic for periodic staff meetings,” Dr. Marrelli adds. All staff should be prepared to recognize emergencies and react appropriately. Emergency situations can happen even when there is no doctor present, and they should at least be prepared to identify and activate EMS, she notes.

Role-playing various emergency situations can ensure both you and your staff are prepared and understand their role. Questions to ask include:

- Who’s calling 911?

- Who starts CPR?

- Who continues if CPR is necessary for an extended period of time?

- Who can use the AED?

- Who, if anyone, is capable of providing medication and/or injections?

Mock drills for different emergencies are essential, says Dr. Shovlin.

“Remember, it might be a staff member or even the OD who is experiencing an event, so is there a back-up plan in place for these scenarios?”

Teach the staff not to panic and to act professionally, says Dr. Rafieetary. “Often, people—even professionals—don’t know how to behave in these types of extraordinary circumstances,” he adds. “Making inappropriate nervous comments or immature acting can exacerbate an intense situation.”

|

|

Emergency oxygen kits could help patients in need. Photo: Joseph P. Shovlin, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

Protecting Your Patients and Practice

Preparation and a clear understanding of how to handle non-ocular emergencies not only protects your patients but also yourself and your practice. Dr. Shovlin advises ODs to carefully document any training with devices (e.g., CPR, AED) and role play. It is also important to make sure that your certifications are up to date and valid. He also recommends creating a written emergency protocol that includes the skills and training of each current employee.

When a medical emergency occurs, thoroughly document the situation, which actions were taken and the outcome. While these emergency situations often fall under Good Samaritan laws to a certain extent (check your local regulations so you know the specifics for your area), ODs must understand the nuances of informed and implied consent and how to approach their patients, notes Dr. Buckingham.

For example, your patient has a vasovagal response. They briefly pass out and when they come to, they are often embarrassed. “A lot of times the patient may want to leave after this,” says Dr. Buckingham. “However, it is your responsibility to make sure they are alert and oriented to person, place, time and event. If they are not, they are legally confused and if anything happened after they left your office the liability comes back to you as the medical provider.”

To determine if a patient can safely leave, Dr. Buckingham asks the following questions: What’s your full name? Where are you? What month is it? What are you doing here? Then, clearly document this interaction and your findings. If the patient answers all of these questions correctly, they can leave, or finish the exam and then leave.

In cases where you believe a patient needs immediate medical care and yet they decline treatment, it is up to you to determine their competence. This is important to protect them as well as your practice.

For instance, when a diabetic patient with dangerously high sugar levels refused to go to the hospital, Dr. Buckingham outlined the urgency and then asked the four questions above before allowing the patient to leave against his medical advice. While patients have medical autonomy and can refuse treatment—barring any special circumstances—it is up to you to take the lead.

In emergency situations, it can be easy to let your flight-or-fight response take over, Dr. Buckingham acknowledges. “Stay with your patient and remember that you are their advocate. You’re not there to magically fix a medical emergency that you’re not trained for, but you can handle basic first aid while also providing comfort and support.”

It is the optometrist’s job to identify the situation and mitigate it until first responders get there. “Don’t hesitate to call 911, even if you’re not sure if it is necessary,” Dr. Buckingham encourages. “Even if the patient doesn’t want to go and ultimately refuses care, EMTs can evaluate the patient. There are no bills generated unless the patient is transported; when there are, those bills are sent to them, not the caller.”

“Don’t take anything lightly,” adds Dr. Shovlin. “Know the signs and symptoms of cardiac arrest, stroke or any other life-threatening event. Things can worsen quickly, so don’t hesitate and be decisive.”

Remember that your role in an emergency situation is to always protect the patients from any further injury, says Dr. Shovlin. For instance, when seizures occur, removing any surrounding potential harm is important without making excessive moves.

“Overall, prepare for medical emergencies by having the right equipment and medications, educating staff with basic and advanced certifications and rehearsing protocols,” he concludes. “Doing so significantly decreases any chance of experiencing an unfavorable outcome when an emergency arises.”

1. Kruthoff C. 911 In the exam lane. Rev Optom. 2020;157(8):56-61. 2. Hypoglycemia (low blood glucose). American Diabetes Association. diabetes.org/healthy-living/medication-treatments/blood-glucose-testing-and-control/hypoglycemia. Accessed March 6, 2023. |