A 56-year-old African American patient presents to your office for a routine eye exam to update his eyeglasses prescription. During the course of the visit you discover that his IOP is 22mm Hg OD, 21mm Hg OS and his cup-to-disc ratios are .70 OD and .60 OS. Now what? Years ago, the answer was: refer. But today, optometrists are licensed and capable of diagnosing and treating patients with this condition in all fifty states. Thus, I diagnosed him with glaucoma, started therapy and will be following him regularly.

For those who are already managing patients with glaucoma, you know how rewarding, challenging and lucrative it can be. For those who are not, here are the essentials of creating a glaucoma practice.

Equipment Upgrades

The first step to incorporating glaucoma care into your practice is investing in the right equipment. The bare minimum equipment to properly assess these patients include:

- Applanation tonometer

- Gonioscope

- Fundus camera

- Threshold visual field analyzer

While necessary, it can be costly and you will have to budget accordingly. This list can cost between $50,000 and $60,000, and it’s only the first round of purchases. The next recommendation would be a nerve fiber analyzer—a GDx or an OCT will cost another $60,000 to $80,000—followed by a corneal pachymeter.

|  |

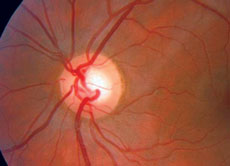

| The patient’s optic nerve head photos help demonstrate the cup-to-disc ratio. | |

Staff Training

This additional equipment also means that you must properly train staff on how to perform the ancillary tests. Commonly, the technician performs the photographs, visual field, etc., and you interpret the results and explain them to the patient. However, staff education should go beyond just teaching them how to perform the tests. They must also be educated on the essentials of glaucoma. Patients will often ask them questions, and having a technician capable of having an intelligent conversation with the patient adds more credibility to your practice.

Patient Protocol

The next step is establishing a protocol for glaucoma suspects and those with glaucoma. In most cases, patients with glaucoma will undergo a variety of different examinations and tests, including a comprehensive examination, visual field examination, gonioscopy, fundus photography, nerve fiber analysis and corneal pachymetry. Here is my patient protocol, as an example:

Glaucoma suspects:

Visit 1

- Comprehensive, dilated exam

- Gonioscopy

- Corneal pachymetry (if not done before)

- Fundus photography

Visit 2

- Intermediate exam/IOP check

- Nerve fiber analysis

Visit 3

- Intermediate exam/IOP check

- Visual field analysis

For all initial work ups, I separate the visits by three or four weeks each. I also try to schedule these appointments during different times of the day because I want to get an idea of the patient’s diurnal variation. Studies show that normal patients exhibit as much as 4mm Hg to 5mm Hg of IOP variation in a 24-hour period. Patients with glaucoma exhibit much more of a fluctuation. If the patient is an established glaucoma suspect, I do these visits roughly every four months.

Be sure to take additional visits into consideration when scheduling. Also, these patients have a potentially blinding disease and may take more time than routine patients.

Glaucoma patients:

Same as above but with a fourth visit for an IOP check, so the patient is in my office every three months instead of four.

To help you provide the optimum level of care for these patients, here’s a closer look at the glaucoma protocol.

|

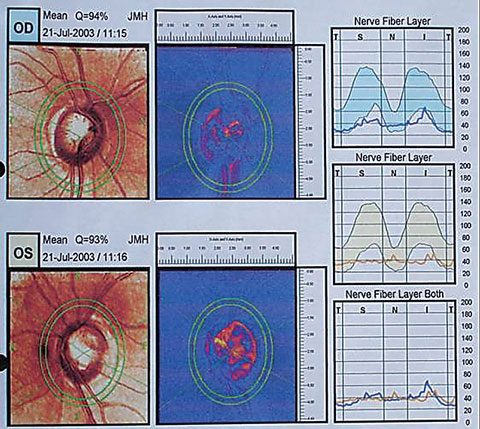

| The patient’s GDx printout shows dramatic loss of the retinal nerve fiber layer. |

The Comprehensive Exam for Glaucoma

Any patient suspected of having glaucoma should have a comprehensive eye examination on an annual basis that includes dilation and more specific components such as a careful slit lamp examination, intraocular pressure (IOP) measurement and optic nerve and nerve fiber layer examination.

Another important step of the initial assessment is the patient’s ocular, medical and family history. For some patients, the information you gather from history taking may be enough to warrant the diagnosis of glaucoma suspect and lead you to order a glaucoma work up. Some of the more common risk factors include advanced age, race (particularly African American and Hispanic), history of elevated IOP, a family history of glaucoma, high myopia and a history of iritis or ocular trauma. Patients who have hypertension, diabetes or any condition requiring the long-term use of corticosteroids are also at higher risk.

These risk factors may help you decide how aggressively you manage these patients. For example, patients with two or more risk factors, or patients with certain risk factors (such as thin corneas), warrant extra attention. For the vast majority of patients, once you have established a diagnosis of glaucoma suspect, you will follow the protocol annually. For a few who are lower risk, you may do every other year, while still seeing them for an annual exam.

When ordering tests and diagnostic procedures to better help you diagnose or manage the condition, your chart documentation must include an order for each specific test requested by you, the treating doctor. Include a short phrase indicating the request, for example, “order visual field in three months” or “gonioscopy/fundus photos performed today.” This documents that additional testing is necessary beyond the comprehensive exam.

Billing tip: When coding for the comprehensive exam, you have two basic options: evaluation and management (E/M) codes or eye codes. The difference between E/M codes and eye codes is the level of service provided and proper documentation. In my practice, I use the eye codes almost exclusively. The two most common codes I use for the comprehensive exam are 92004 (comprehensive eye exam, new patient) and 92014 (comprehensive eye exam, previous patient).

Gonioscopy (code: 92020). The visual examination of the anterior chamber angle, or gonioscopy, is part of the standard of care for every glaucoma patient and glaucoma suspect. What we loosely refer to as glaucoma is actually primary open-angle glaucoma—but you can’t call it that unless you’ve visualized the angle with gonioscopy and know that the angle is open. Many practitioners often overlook the procedure because they know roughly 90% of all glaucoma cases are open-angle glaucoma. However, 10% have a secondary mechanism, such as anatomically narrow angles, pigment dispersion or pseudoexfoliation. Perform gonioscopy on all glaucoma patients and suspects every year because the configuration of the angle can change as a result of pupil size, ciliary tone, iris configuration and crystalline lens size.

Billing tip: For billing purposes, you can perform gonioscopy on the same day as the comprehensive eye exam and the same day you perform other procedures such as fundus photography or visual field analysis. I suggest performing gonioscopy the same day as applanation tonometry because the cornea will already be anesthesized.

Visual field testing (code: 92083). The visual field (VF) test is the most common auxiliary test we order for glaucoma patients. Although many new methods have been developed to assess visual function in glaucoma and glaucoma suspect patients, perimetric evaluation of the glaucomatous visual field remains a cornerstone in the protocol.

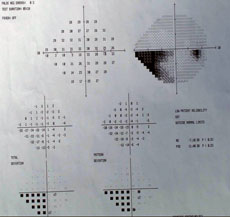

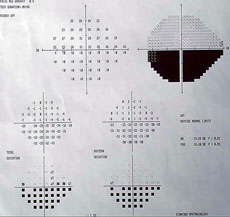

|  |

| Visual fields show the glaucomatous defects, confirming a diagnosis of glaucoma. | |

Visual field testing depends on the severity of the disease and the risk of progression. You should perform a VF test yearly on glaucoma patients or glaucoma suspect patients who have stable test results. For more progressive or high-risk cases, perform VF testing every six months, and every three months for advanced glaucoma. One of the most common scenarios in which multiple testing is required is if the first VF test demonstrates glaucomatous defects or significant changes from previous tests. The second test verifies the results and checks for repeatable defects.

Billing tip: VF results aren’t bundled with other tests, so you can perform them on the same day as gonioscopy and a complete eye examination. You can perform them on the same day as scanning computerized ophthalmic diagnostic imaging (92133) or fundus photography, but you lose 20% reimbursement for multiple procedures done on the same day.

Fundus photography (code: 92250). Stereo photography of the optic nerve head is the minimum standard of care for any glaucoma patient. In most cases, you’ll perform fundus photography at the end of the comprehensive eye examination with the pupils dilated. Doing so provides you with an objective measurement of the C/D ratio and a comparison for future photographs. Usually, insurance will not reimburse fundus photography if you perform it on the same day as scanning computerized diagnostic imaging.

Billing tip: Perform stereo photography of the optic nerve head structure annually for most glaucoma and glaucoma suspect patients. Once you have several years of photos, you can use serial analyzing software to help you detect subtle changes.

Optic nerve and nerve fiber analysis (code: 92133). The analysis of the nerve fiber layer is a recent addition to the standard of care in glaucoma workups. Generally, you can perform optic nerve and nerve fiber analysis once a year, or every six months for patients who have advanced glaucoma. You should use a red-free filter on your slit lamp to evaluate the nerve fiber layer, as well as the objective data from a GDx nerve fiber layer analyzer or an OCT for objective, reproducible measurements to help detect subtle changes.

Billing tip: Typically billed bilaterally, these are reimbursable under the code for scanning computerized ophthalmic diagnostic imaging.

IOP measurement. Even though glaucoma is no longer defined by IOP, its measurement is an essential part of diagnosis and management. When done as part of a comprehensive or intermediate eye exam, it’s considered an incidental component of the exam with no additional reimbursement. The most common scenario is when you’re following a patient who needs their IOP checked after three or four months. The doctor typically checks for any changes in health and vision, updates medications and checks IOP along with a slit lamp examination. Specific items that are cause for concern are elevated IOP (above 21mm Hg), significant asymetric IOP, or a patient with significant fluctuation. Historically, research suggested IOP is highest in the early morning, gradually falling throughout the day. However, newer data suggests that IOP may actually be the highest at night.

Billing tip: The one exception to the rule of not being reimbursed for IOP measurements is serial tonometry (code: 92100). Tonometry is considered serial when you measure IOP at least three separate times during the course of one day. This test is most commonly used in patients who have progressive glaucoma despite the appearance that they are at or below target IOP. Another common situation warranting serial tonometry is if you suspect normal tension glaucoma (code: H40.123).

Corneal pachymetry (code: 76514). With the release of the Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study (OHTS), the corneal pachymeter quickly became part of the standard of care for glaucoma. The OHTS concluded that eyes with relatively thin corneas—555µm or less—had a greater risk of developing glaucoma than those with thick corneas—558µm or greater.

Billing tip: Measure corneal thickness on every glaucoma or glaucoma suspect patient. Unlike other glaucoma testing, which is generally performed on an annual basis, corneal pachymetry is only done once in an individual’s lifetime.

Vision vs. Medical

Many optometrists face a dilemma when a patient is in their office for a routine eye exam through a vision plan but they discover some finding leading to a diagnosis of glaucoma suspect. If the patient shares that he is at risk due to his family history, for example, you may consider initiating a medical visit from the beginning. Otherwise, once you proceed with a routine vision exam and uncover suspicious findings, you must have the patient return for glaucoma-specific testing, which will then be billed to the patient’s medical insurance. This creates a clear-cut distinction in the patient’s mind as to what was routine and what was medical. However, ensuring the patient returns for glaucoma work up can be challenging.

Patient Education

The next step is patient education, which is critical for patient compliance. The informed patient who fully understands the true blinding nature of glaucoma is more likely to adhere to treatment and follow up. Patients who only know what to do without understanding the reasoning will not be as compliant as those who are well-educated.

This can be very simple—a detailed conversation or a brochure. You could also incorporate patient education videos, which can be viewed while a patient is dilating.

Treatment

Our clinical goal is to slow the progression of the disease so the patient does not go blind in their lifetime. We lower IOP as a mere practicality, because it is the only significant risk factor we can change.

There is some consensus as to when a glaucoma suspect patient converts to glaucoma. The most obvious of these is:

- A repeatable VF with a pattern consistent with glaucoma.

- A repeatable or progression defect of the nerve fiber layer.

- Progressive enlargement of the C/D ratio.

- An IOP level warranting treatment in the absence of the above findings. I treat any patient with an IOP of 28mm Hg or higher and corneas of thin or average thickness.

The first step in treating these patients is to establish a target IOP at which the patient will not demonstrate progression. It is based on many factors such as age, starting IOP, disease severity and thickness of the cornea. However, a target IOP is no more than an educated guess and should be re-assessed at every visit.

The vast majority of patients are started on a prostaglandin such as Xalatan (latanoprost, Pfizer), Lumigan (bimatoprost, Allergan) or Travatan (travaprost, Alcon) OU QHS. These agents demonstrate excellent efficacy and tolerability with great safety profiles. However, they can be very expensive, costing $30 to $80 a month. For patients who cannot afford this, I often start them on a topical beta-blocker, which is usually $5 a month. In my mind, a patient consistently taking a beta-blocker is better than a noncompliant patient on a prostaglandin.

The Long Game

Once patients are diagnosed with glaucoma, they should be in your practice every three months to check for progressive changes. This is also an optimal time to continue educating them about compliance. More than anything, they need your support and positive outlook. Although most patients will be successfully managed, a small handful will still progress even when both of you are doing everything right.

To optimize diagnosis and treatment of patients with glaucoma and glaucoma suspects, ODs must adapt their patterns of practice to accommodate changes in patient flow and testing, scheduling and proper medical billing. In all situations, the key to your glaucoma practice is for you to administer the standard of care and bill appropriately for your services. Mastering both areas will provide the highest level of care for your patients and the best return on investment for your practice.

Dr. Gupta is clinical director for The Optometric Referral Center at Gupta EyeCare in Milford, CT.