Just outside of downtown Los Angeles, a big box retailer employs two optometrists. About twice a week, a patient will enter for a refractive exam and leave with a glaucoma diagnosis. That’s when “things get dicey,” explains one of the clinicians, who didn’t want to share his name. To save himself the trouble, he sends them to a nearby hospital.

This doctor’s situation isn’t uncommon. And the constraints he faces don’t stem from his retail setting alone. If anything, it’s emblematic of a blind spot that affects a sizable chunk of optometry—private practitioners and corporate ODs alike. When encountering glaucoma patients, only about one-third of optometrists practice to the full extent of their scope of practice. The rest pull the trigger on referral earlier than they might otherwise need to.

And that’s a shame, because America is on the verge of a glaucoma influx. In 30 years, the rate of glaucoma is projected to more than double, from today’s three million to more than seven million.1,2 Prevalence isn’t even clear because more than half of glaucoma cases in the US remain undiagnosed.3 And with the number of ophthalmologists in the United States continuing to erode, patients are going to look to optometrists to fill that gap.4

When they don’t, some may chalk it up to a dearth of clinical expertise in glaucoma care or else blame economic pressures dictating that optometrists focus on selling glasses and contacts.

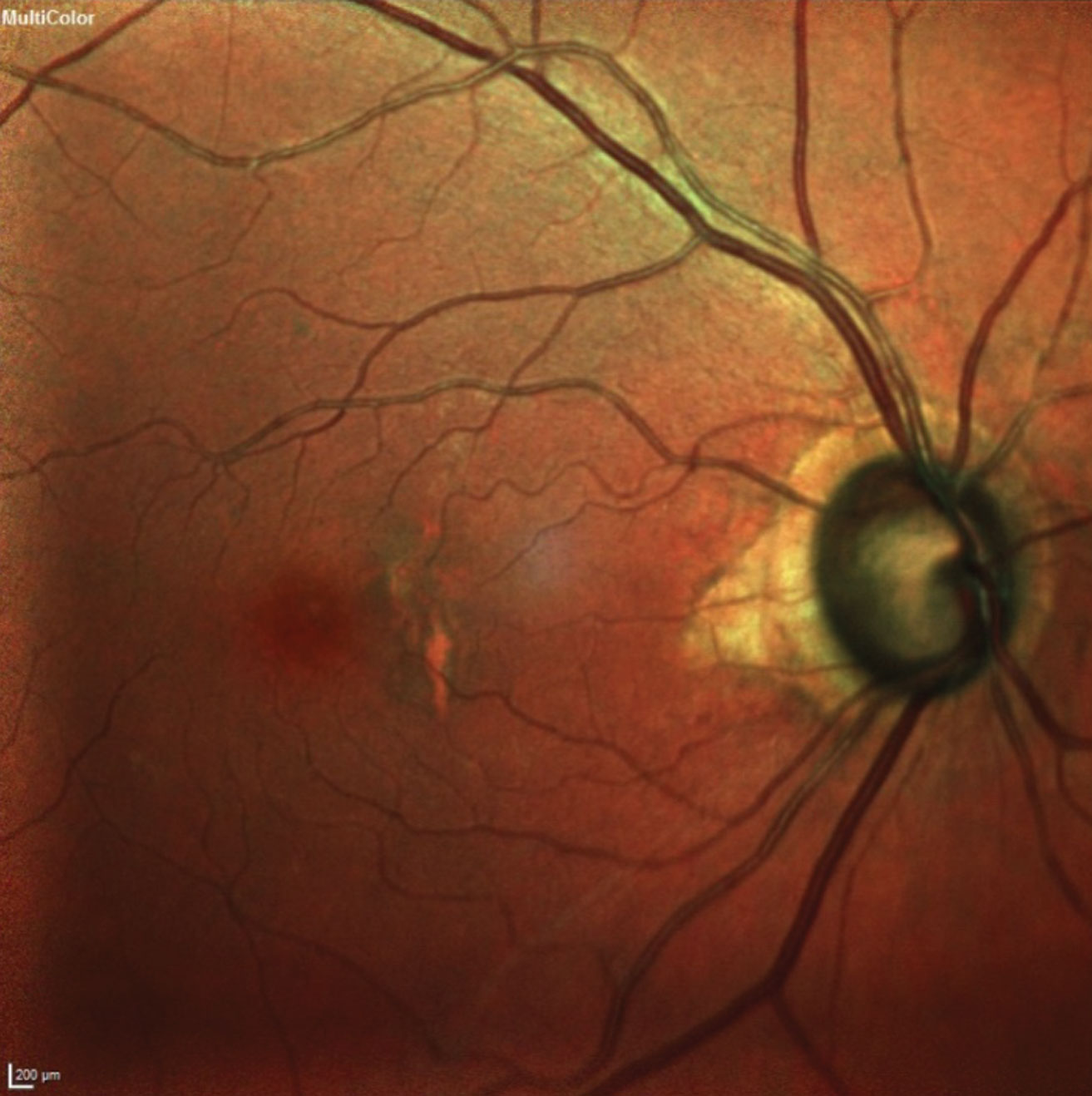

|

| This 77-year-old patient’s fundus image shows advanced glaucomatous damage and macular changes consistent with her age. Photo: James L. Fanelli, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

But for many optometrists, neither are true. The fact is that our big-box doctor is quite skilled at medical treatment, has an optical coherence tomography (OCT) device in his office, and communicates fluently with his multilingual community. The retailer doesn’t prevent him from treating glaucoma—circumstances do. The obstacles have a lot more to do with the laborious time commitment and insurance-related red tape associated with glaucoma.

These are the key findings of a survey conducted by Review of Optometry, in which 364 optometrists shared their frustrations and aspirations in glaucoma care. Here’s what they told us.

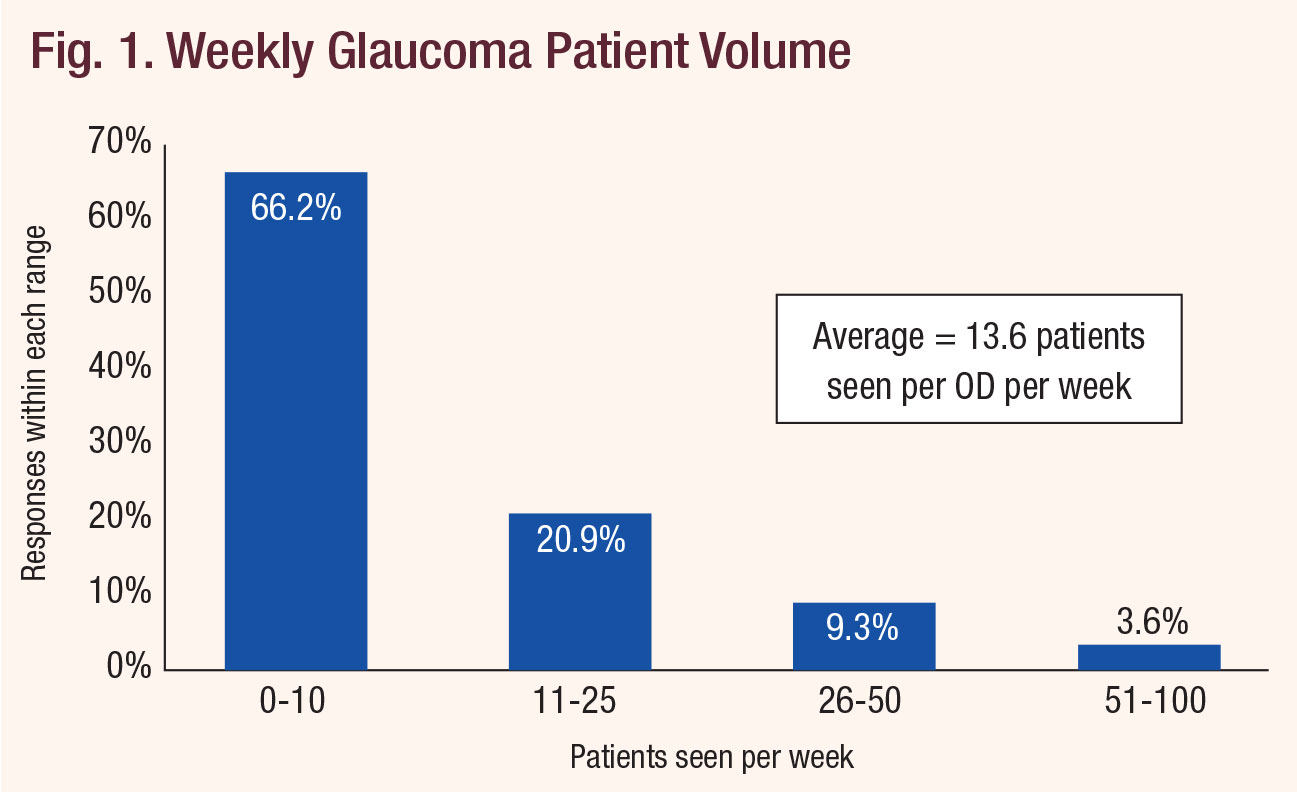

|

| Fig. 1. Weekly Glaucoma Patient Volume. Click chart to enlarge. |

Overcoming Reluctance

For optometry to realize its potential in glaucoma care, two basic things need to happen: patients have to come into the clinic, and doctors have to be ready to provide the care they need. Each component faces setbacks, our survey found.

First, take patient access. Respondents to this survey reported that, on average, 13.6 glaucoma patients or suspects present to their practices each week. That number was skewed slightly higher by a few respondents who report seeing 100 such patients per week. The most commonly reported number (the mode, in statistics parlance) was 10 patients per week. Another way of thinking about it: 66.2% of optometrists in our survey see 10 or fewer glaucoma patients or suspects per week (Figure 1). That just won’t cut it when there’s a population of about three million glaucoma patients needing anywhere from one to four eye exams per year.

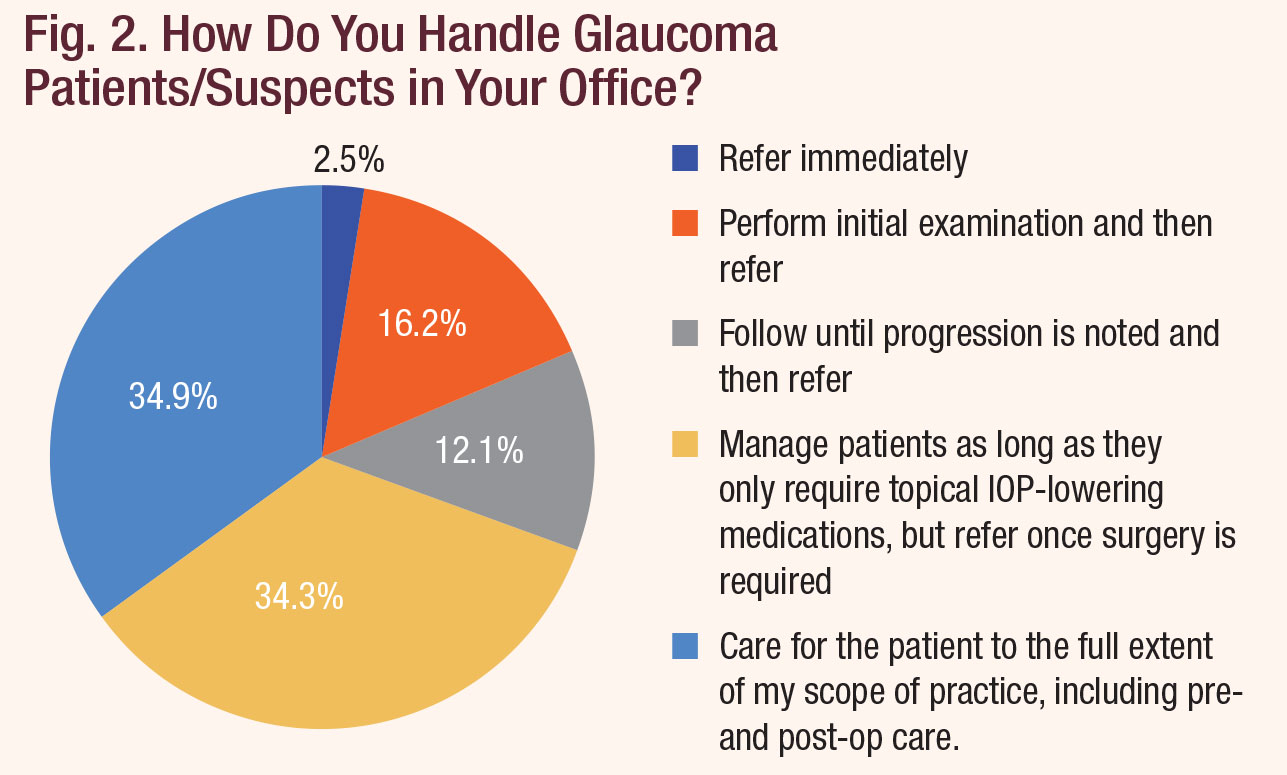

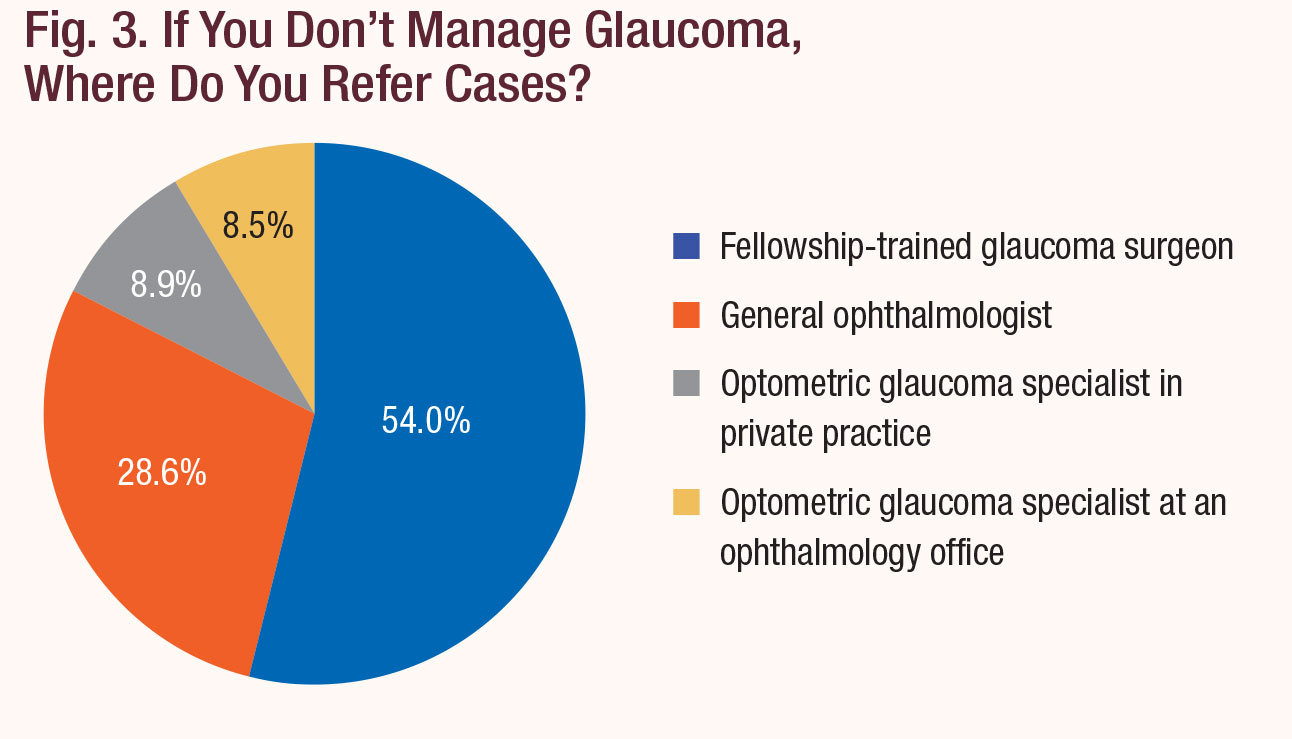

And what happens when those patients do arrive? About one in five leave that day with a referral, most often to an ophthalmologist, according to our survey respondents (Figures 2 and 3). Another 12.1% of ODs treat only until they note progression, after which they too refer out. Only 34.9% of respondents told us they care for the patient to the full extent of their state’s scope of practice law, including the provision of pre- and post-op care. Another 34.3% do actively manage the patients up to the point when surgery is required, however.

On balance, that combined 69.2% of ODs who are treating glaucoma does indicate broad acceptance of this as a fundamental optometric task; the challenge ahead is to break down barriers to entry for the other 30.8% and to help everyone push the envelope on the care provided in their practices.

|

| Fig. 2. How Do You Handle Glaucoma Patients/Suspects in Your Office? Click chart to enlarge. |

Optometrists fought for decades to obtain the privilege to treat glaucoma medically. It’s now a standard aspect of training and education. Michael Chaglasian, OD, president of the Optometric Glaucoma Society, fears that, if optometrists don’t embrace a larger role in the care of glaucoma patients, one that partners with ophthalmic surgeons, “ophthalmologists will find some other profession—physician assistants, medical assistants, ophthalmic assistants,” to partner with instead.

With some states still less than 20 years into topical glaucoma treatment indications—and Massachusetts still locked out altogether—patients aren’t always aware of how broad optometry’s scope of practice is. To many patients, optometrists might still be just the glasses-and-contacts people. Convincing them otherwise is going to require a little patient education. The American Optometric Association’s “Think About Your Eyes” campaign educates the public on vision health and promotes the importance of annual comprehensive eye exams. But a number of respondents asked to see something specific to glaucoma. “A public awareness campaign that ODs treat glaucoma and a legislative push to allow privileges as-taught would be game changing,” wrote one doctor from Blue Island, IL.

On a smaller scale, optometrists can take it upon themselves to advocate for the profession and explain to patients that optometry is a primary care discipline that has the ability to treat almost any eye disease that doesn’t require surgery.

Still, the loud voice of the medical lobby keeps optometry back, too. “The requirement in Texas to have to comanage glaucoma with an ophthalmologist is a pain and might be a deterrent for many,” a reader from Fredricksburg, TX, notes.

|

| Fig. 3. If You Don't Manage Glaucoma, Where Do You Refer Cases? Click chart to enlarge. |

Headwinds

Review’s survey finds some optometrists have the expertise to treat, but not the tools (literal or administrative) while others say they do feel their clinical skills need polishing. Some of the strongest motifs in our survey responses include:

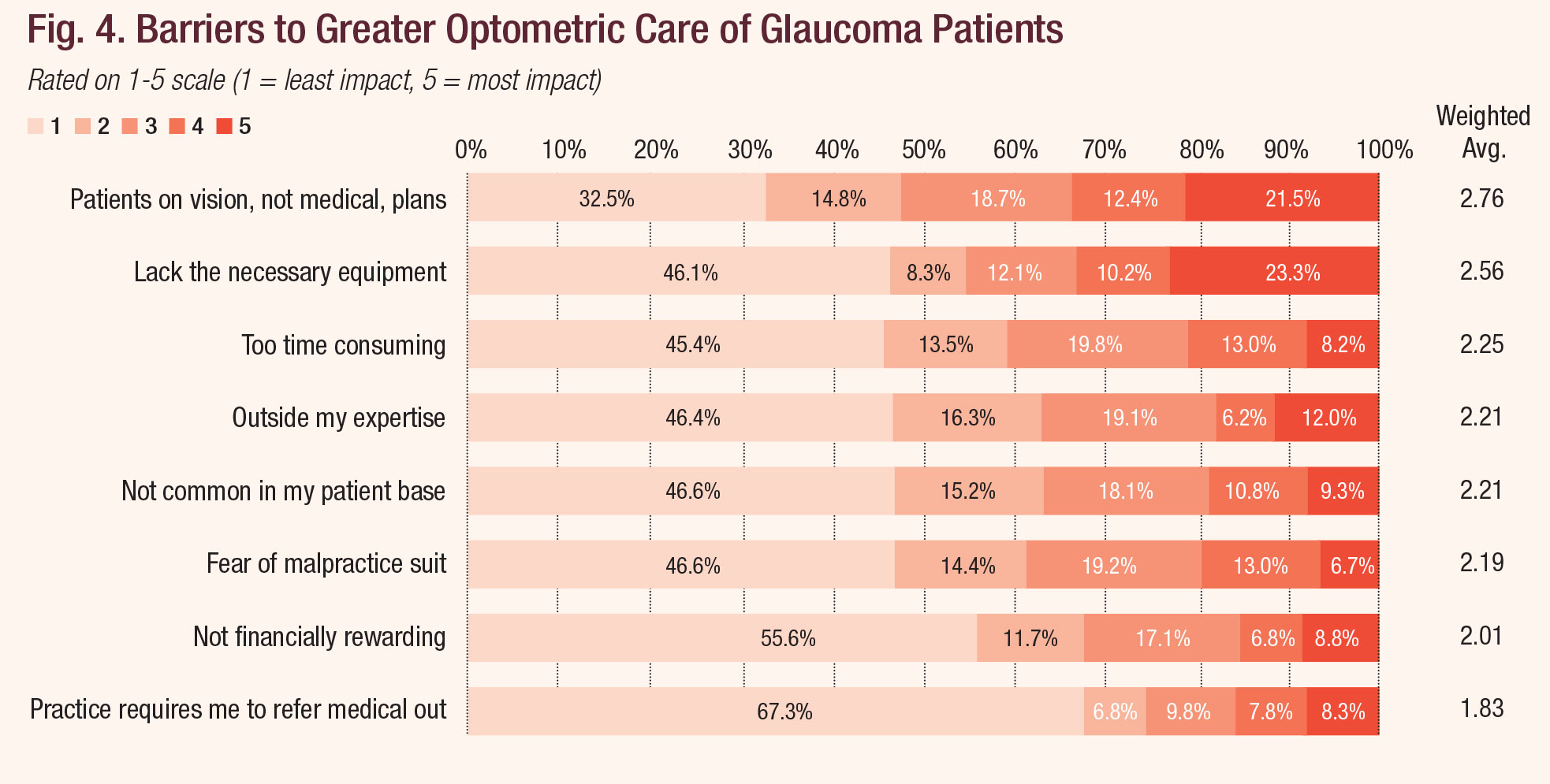

Insurance hassles. The most heavily weighted response to the survey, with more than a third of respondents ranking it as either the biggest or second biggest barrier to embracing glaucoma care, involves issues with billing and coding (Figure 4). Many of those who answered Review’s survey say they can’t bill medical insurance. “There are too many panels that are OMD-only, or just closed to ODs,” a reader from Laguna Niguel, CA, commented. “This forces me to refer a lot of patients out for something I can manage and treat in-office.”

Others encounter pushback from patients who can’t understand why their optometrist is suddenly asking about medical insurance when they’ve only ever asked about a managed vision plan.

The big-box optometrist in our first example owns his own OCT, but still doesn’t bother billing insurance. “I haven’t even tried it,” he says. “We just charge a $35 flat fee for OCT—that’s for the scan and the report. Typically, for a glaucoma work up, we’ll do the OCT and we’ll do the threshold visual field for another $20. That’s really affordable, in my opinion.”

He’s also more apt to simply refer them out. “It’s easier for me to do it that way, because I don’t have the knowledge or the resources to do proper coding,” he explains. If they’re uninsured, he’ll do what he can by starting them on drops, but eventually refers them to an MD.

It wasn’t always this way. “When I first started, I did try to treat [glaucoma] and kept my fees very low, but it didn’t work out. I found myself spending more time explaining the things I need to do to provide good care and when I tell patients the cost of the drops, it usually stops them dead in their tracks.” That’s not ideal when your two-doctor practice sees 40 patients a day, seven days a week.

Diagnostic tools. A close second to insurance headaches, our respondents say, is a simple lack of necessary equipment, with 23.3% ranking this a “5 out of 5” in negative impact on their ability to practice. OCT instrumentation “is now at the low end of $40,000—no longer $60,000 to $80,000, but still huge for many small offices,” explains Dr. Chaglasian.

There’s a bit of a Catch-22 problem that keeps many practices from getting more involved in glaucoma: you can’t pay for the equipment without the patients, and you can’t build the patient base without the equipment.

“If a practice mostly sees younger families for refractive care, they might not have the volume to justify the equipment purchases,” a reader from Mansfield, OH, explains. “That, in turn makes it difficult for the doctor to build a glaucoma practice and gain confidence and experience. I think there are still a substantial number of practices that work this way and that is the most common reason I hear in practices that choose not to treat glaucoma.”

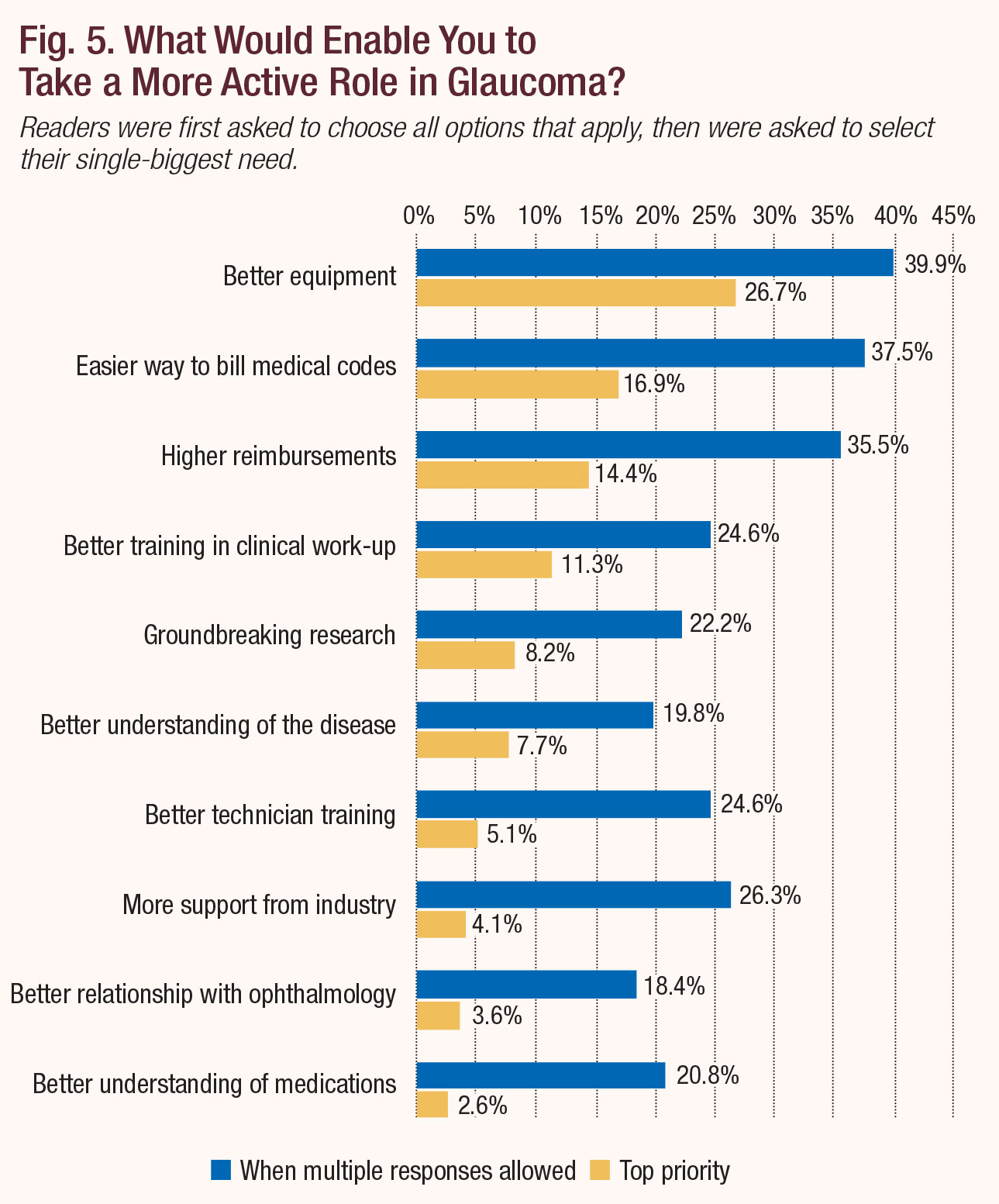

When asked what would enable them to take a more active role in glaucoma, respondents to our survey put ‘better equipment’ at the top of their wish lists (Figure 5). Nearly 40% chose it as something that would help. Tellingly, when forced to name the single most important factor that could turn the tide for them, 26.7% still picked better equipment. The second most commonly cited reply was, not surprisingly, easier ways to bill medical codes; still, the need for equipment outpaced it significantly.

|

| Fig. 4. Barriers to Greater Optometric Care of Glaucoma Patients. Click chart to enlarge. |

Expertise. But simply having equipment isn’t enough. “If they buy an OCT, they still need to learn how to use it,” notes Dr. Chaglasian.

“Classroom teaching helps a little bit,” Dr. Chaglasian explains, “but when the optometrist can come to a small group discussion and compare it with the IOP, the threshold visual field and the fundus photographs, and re-teach how to take care of a glaucoma patient, that can get them over their discomfort.”

In Review’s survey, 12% ranked “outside my expertise” as the number one reason they don’t treat glaucoma patients to the full extent allowed by their state. When asked what would help them take a more active role in glaucoma treatment, respondents again indicated that increasing their clinical acumen would get the ball rolling. Specifically, 24.6% selected “better training in clinical work-up,” 20.8% said “better understanding of the available medical treatments” and 19.8% answered “better understanding of the disease.”

Prescribing topical drops for glaucoma is a hard-won privilege optometrists spent much of the 1990s fighting to obtain.5 Texas only approved it in 1999, Vermont in 2004.5 Massachusetts remains the only state in the nation without glaucoma indications for optometrists.5 And yet, many ODs allow ophthalmology to dominate the field, as demonstrated by a recent study that shows MDs prescribe both a wider variety of glaucoma medications than optometrists (8.1 vs. 3.6) and to more patients (222.7 vs. 60.4).6

Part of this phenomenon can be attributed to the optometrist’s career path, several experts speculated. Many optometrists fresh out of school opt to work for “corporate optometry”—that is, a retail chain primarily focused on frames and contact lens sales—before even considering opening up their own practice. This can help them catch up on student loan bills and establish some stability before taking on the financial commitment, risk and long hours of practice ownership. However, with so much of their day centered around refraction (and potential rules put in place by their employer), they may fall behind in the latest in medical knowledge.

A doctor with a Pearle Vision franchise simply answered that she “can’t bill medically” so she refers all suspects to a general ophthalmologist. In Review’s survey, 8.3% said the number one reason they don’t treat glaucoma is because their practice requires them to refer out. But even privately run optometric offices can fall into a “refractions-and-eye-exam-only” routine.

Whichever the case, “for many of these practitioners, there’s been a long gap between the time they were in school and in training programs and when they got to a location where they can practice to the fullest extent of their education,” says Dr. Chaglasian.

|

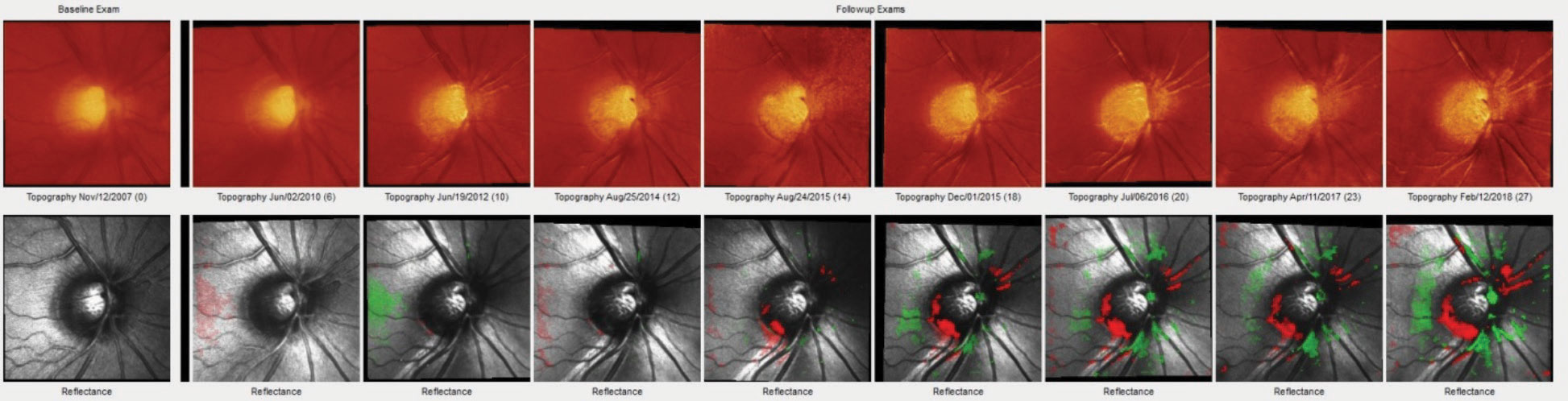

| Heidelberg Retina Tomograph-3 imaging shows a distinct change in the inferotemporal neuroretinal rim of a 57-year-old patient. This series shows this change progress over the course of 11 years. Monitoring this kind of change over time is elemental to caring for glaucoma patients and suspects. Photo: James L. Fanelli, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

Taking Action

Those optometrists who feel they’ve plateaued—at whatever level—in how they address glaucoma in their practices do have plenty of ways to push through.

Ask for help. Encouragingly, optometrists are sharing expertise, and patients, with their colleagues. “I have an OD contact in a large surgical practice I bounce diagnostic info off all the time—wish there were more than one available,” wrote an OD from Hilliard, OH. “I have recently resorted to sending scans to other classmates for their input and that has been fruitful.” OD-to-OD referrals comprised 17.4% of the patient hand-offs cited by our survey respondents.

Not every optometrist will be able to invest in all equipment needed, but that doesn’t mean it’s off-limits to you. If you don’t have an OCT, one of your optometric colleagues in town likely does, explains James Fanelli, OD, a North Carolina clinician with a special interest in glaucoma. Then, you can have that doctor send you the results, they can collect their portion for the technical component using code 91233-TC and you can collect for the interpretation, code 92133-26.

The same principle can be applied to fundus photography, pachymetry or threshold visual fields.

Get paid the right way. It’s a bit of an understatement to point out that there are no easy ways to simplify the state of medical insurance in the United States. But experts have a few thoughts to share. If you’re not already taking private medical insurance, you could consider attending courses on proper billing and coding at an optometric conference. The downside there is that these courses rarely qualify for relicensure, as coding is often considered “practice management,” explains John Rumpakis, OD, a consultant on coding and practice strategy. But, he says, go anyway and fill in that gap in your knowledge. One-time commitments like these can get you started down the road to providing better care to that coming influx of glaucoma patients.

Those afraid of billing improperly need to keep a few pointers in mind. For starters, when a patient appears for a vision health checkup, that visit is billed to a patient’s managed vision care plan, not medical insurance—even if you find a medical problem such as glaucoma. “It’s always the purpose of the visit, never the findings” that you code for, Dr. Rumpakis says.

However, once the basic comprehensive exam portion of the visit is completed and the doctor makes a diagnosis of the patient as a glaucoma suspect, the medical insurance company is billed for any tests that the doctor orders on the basis of that finding. Both can be billed during one visit—but a strict line is drawn between the visit, the refraction and the comprehensive exam, which is billed to the managed vision plan and the rest of the appointment. This is where the doctor has to explain to the patient that they’re showing potential glaucomatous changes and it will require additional testing to learn more. Those additional tests are billed to the medical carrier. Clinicians should explain that, if patients haven’t yet met their deductible, they’ll be responsible for the full cost.

Of the five medically necessary diagnostic tests in glaucoma—gonioscopy, pachymetry, threshold visual fields, fundus photography and OCT—the first three are allowed on the same day as the general exam but, Dr. Rumpakis explains, fundus photography and OCT are generally not allowed on the same day, except in the case of a vision-threatening necessity. Misusing a CPT modifier to get around this—even if your intentions are good and you’re just trying to save your patient a second trip—is a violation of carrier rules.

Not all glaucoma suspects need to be tested with every piece of equipment you can get your hands on. “You can’t apply the same protocol across the board for all glaucoma suspects,” explains Dr. Rumpakis. “Clinicians have to look at the individual, their personal history, their physical exam and their family history, and then determine which tool is going to be most appropriate and effective.” When coding, your office is responsible for properly establishing the path of medical necessity from what you observe in the general exam to ordering a specific series of tests appropriate for that patient.

|

| Fig. 5. What Would Enable You to Take a More Active Role in Glaucoma? Click chart to enlarge. |

Build your knowledge. A recent report into dry eye defines the condition as the “loss of homeostasis on the ocular surface.”7 Minus the ocular surface part, that’s a fitting description for what you’re looking for when monitoring glaucoma suspects and confirmed cases, according to Dr. Fanelli. Their visits, he says, “are geared toward stability. If things change, you know something needs to be done differently.”

“Right now, there’s no place to go that’s widely available for clinical guidance on helping ODs overcome their anxiety and fear about not knowing what to do with a patient,” Dr. Chaglasian explains. But he has an idea. The OGS ran a pilot project last year that brought together 45 to 50 optometrists across the country in a weekly web-based case discussion group on glaucoma care. Think of it as an interactive classroom, unencumbered by COPE oversight. There, “doctors could present their own cases and ask questions like, ‘When do I add the next medication?’, ‘What should I look for on an OCT?’ or ‘When do I perform this type of visual field?’” The format, should it take off, would exist purely for learning. That outlet isn’t currently available, but the OGS hasn’t given up on it. A looser form of candid, collaborative discussion can be found online at ODs on Facebook and similar groups.

Dr. Fanelli shared a more DIY idea. “Try going to a fellow OD’s office who does treat glaucoma and asking if you can spend a couple days with them.” It couldn’t hurt to ask.

|

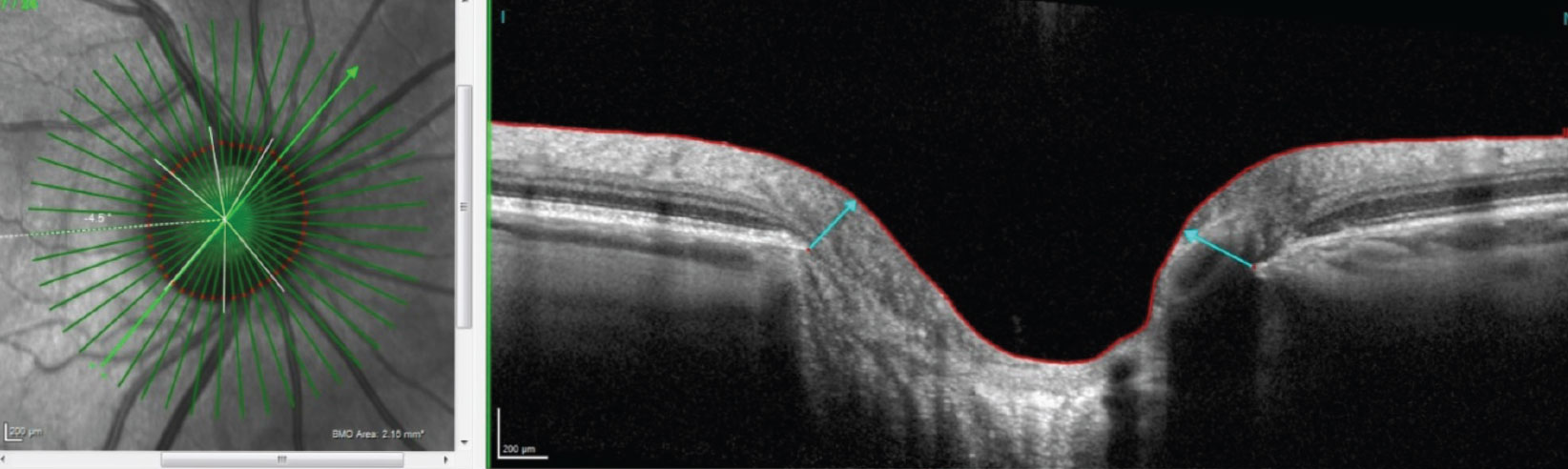

| OCT images, such as this radial OCT of a steep nasal margin and sloping inferotemporal margin, offer deep insight into glaucoma patients. Photo: James L. Fanelli, OD. Click image to enlarge. |

Being the Change

A conservative mindset erroneously prevails throughout optometry about glaucoma care. “Optometrists worry about the liability,” Dr. Rumpakis says. “They get scared and think ‘Oh, my god, the patient’s going to go blind.’ What they don’t understand is that the liability with failing to diagnose significantly outweighs the liability with losing somebody’s sight.” The vast majority of glaucoma is a slowly progressing disease, he explains, and you have plenty of time to assess and formulate a plan if you’re monitoring a patient appropriately—two to three times a year.

One survey respondent explained why they don’t treat glaucoma patients to the full extent allowed by their state. “I practice in California. Only recently have we been able to treat glaucoma. The glaucoma specialist in my area confuses me. He tends to disagree and not treat patients, only to treat them a year or two later. I also feel patients are calmed by a specialist and would prefer to be watched by them. Glaucoma is a big responsibility and losing vision is scary. I would feel comfortable comanaging with an OD-friendly ophthalmologist until I felt more comfortable managing them alone.”

This doctor is exactly who Dr. Fanelli has in mind when he says advocates for optometrists to take on a bigger role in glaucoma, because ophthalmology will always try to take it from you, and relying on them at the first warning sign permits it. “If you’re punting patients out the door, you’re never going to develop that confidence. If you’re referring most patients, you’re never going to get any better,” Dr. Fanelli says.

“Get up to the edge of your comfort zone and step just a little beyond it. Work there for a couple of months. Then, when you check in on the barrier of your comfort zone again, you’ll find it’s moved,” he says. “That’s when you step over it again.”

1. Bright Focus Foundation. Glaucoma: Facts & Figures. www.brightfocus.org/glaucoma/article/glaucoma-facts-figures. June 27, 2019. Accessed February 14, 2020. 2. Quigley H, Broman A. The number of people with glaucoma worldwide in 2010 and 2020. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90:262-7. 3. Swanson MW. Undiagnosed and Over Diagnosed glaucoma in the United States. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53(14):6379. 4. Shah M, Knoch D, Waxman E. The state of ophthalmology medical student education in the United States and Canada, 2012 through 2013. Ophthalmol. 2014; 121(6):1160–3. 5. Kekevian B. Expanding scope of practice: lessons and leverage. Rev Optom. 2018;155(10):34-46. 6. Janetos T, French D, Beauont J, Tanna A. Geographic and provider variations in ocular hypotensive medication claims among Medicare Part D enrollees. J Glaucoma. 2019 Feb;28(2):e29-e33. 7. Craig JP, Nichols KK, Akpek EK, et al. TFOS DEWS II definition and classification report. Ocul Surf. 2017;15(3):276-83. |