In May 2003, a local cataract surgeon referred a 75-year-old white female to my office after she underwent bilateral YAG capsulotomies. Her primary-care medical doctor referred her to the local cataract surgeon because of decreased vision; the cataract surgeon determined that she would be helped by the capsulotomies. She had undergone uneventful bilateral cataract surgery three years earlier.

Her medications included Aleve (naproxen sodium, Bayer HealthCare) p.r.n. for arthritic pain, 325mg aspirin q.d. and an unknown antihypertensive medication also taken q.d. She reported no allergies to medications.

Diagnostic Data

At this first visit to me, her uncorrected acuity was 20/60 O.D., 20/60 O.S., and 20/50 O.U. Best-corrected acuity was 20/20- O.U. through hyperopic astigmatic correction. Pupils were equal, round and reactive to light and accommodation with no afferent pupillary defect. Extraocular motilities were full in all positions of gaze.

A slit lamp examination of her anterior segment was unremarkable. Her anterior chambers were deep and quiet. Clear corneal incisions were present and well healed. Both corneas had a moderate amount of guttata. Applanation tensions were 26mm Hg O.D. and 24mm Hg O.S.

Through dilated pupils, the posterior chamber IOLs were well centered in the capsular bags, and both posterior capsules were opened following the YAG capsulotomies.

|

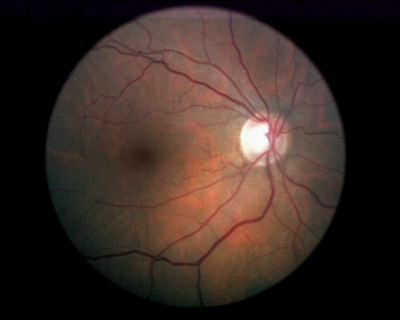

| The right eye of the patient three months after initial presentation. Note the resolving Drance hemorrhage at 7 o"clock. |

Vasculature was characterized by slightly attenuated arterioles in both posterior poles, along with findings consistent with grade II arteriosclerotic retinopathy. Both maculae were characterized by dry granulation and clumping of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), but there was no edema or evidence of subretinal neovascular membrane formation. Her peripheral retinal examination was unremarkable.

I took stereo optic nerve images on the initial visit and asked the patient to return in 30 days for a full glaucoma workup. I also prescribed eyeglasses for her.

She returned three months later. At this time, applanation tensions were unchanged. Threshold visual fields demonstrated a superior arcuate scotoma O.D. and scattered paracentral defects O.S. between 10 and 20 degrees from fixation. Her optic nerves were unchanged from the initial appearance, except for a reduction in the size of the nerve fiber layer hemorrhage O.D.

I diagnosed glaucoma based on several findings and risk factors, including ocular hypertension, attenuated retinal arterioles, and the presence of the nerve fiber layer hemorrhage O.D. The optic cups were not excessively large, but they did not follow the ISNT rule. I prescribed Lumigan (bimatoprost, Allergan) O.U. q.d. h.s. and asked her to return in two to three weeks for re-evaluation.

The patient did not return until three years later, at which time she complained of decreased vision in both eyes especially at night. Current meds included Diovan (valsartan, Novartis), Plavix (clopidogrel, Bristol-Myers Squibb/Sanofi Pharmaceuticals), Synthroid (levothyroxine, Abbott Laboratories), Nexium (esomeprazole, AstraZeneca), aspirin and Boniva (ibandronate, Roche Laboratories). She discontinued the Lumigan on her own.

Best-corrected acuity at this visit was 20/25- O.D. and 20/40- O.S. Applanation tensions were 30mm Hg O.D. and 28mm Hg O.S. Optic nerve cupping had increased to 0.60 x 0.80 O.D. and 0.65 x 0.90 O.S. Her macular evaluation and image overlays were consistent with her visit three years earlier.

I asked the patient why she did not come back three years earlier and why she discontinued the Lumigan. She said that she felt as though she was seeing well with her glasses and that she didnt need to be seen again. She said that she continued to take the Lumigan until the bottle emptied.

Discussion

All clinicians who manage glaucoma patients will come across scenarios such as this regularly. Many patients, for whatever reasons, discontinue therapy. One of our goals should be to minimize these instances, which can oftentimes be challenging.

In my experience, newly diagnosed glaucoma patients generally tend to fall into three categories:

1. The ideal patients. These patients understand the situation and are very attentive and attuned to the disease and its complications. They are genuinely concerned about their eye health and are compliant.

2. The deny-ers. These patients dont believe anything is wrong. I see fine, and my eyes dont hurt. We have all seen these patients. They generally are the ones who are noncompliant.

3. The attempters. These patients seem to understand the risks and benefits of treatment vs. non-treatment, so they begin therapy and follow through for some time, even as long as several years. For some reason, they become lost to follow-up. They may move, may no longer be able to afford their medications or may change doctors. The challenge with this group is to keep their interest level high in their own care.

Whichever category our newly diagnosed glaucoma patients fall into, one effective tool can help guide them into the first category: communication. Communication has many forms, including verbal, body language and confidence, and the look and feel of your office.

Verbal communication is especially important with glaucoma patients. If you are new to managing patients who have glaucoma, you will probably try various iterations of a brief but effective explanation of glaucoma before you settle on your own personal version. Keep in mind, there is no perfect explanation. The best and most efficient explanation is the one that works best for the patient. But, whatever words you choose, and how you put them together, be certain that the explanation is understandable to each patient. You may need to modify what you say and how you say it to each patient.

Start with the basics, but tailor your discussion for each patient. With some patients, the basics may be sufficient to get the point across; other patients may be better persuaded with a more technical discussion.

You must be able to get patients to buy into the concept that they are an integral partprobably the most important partof their own treatment. I like to use the team concept analogy: I cannot help the patient if he wont help himself, just as he cannot diagnose the problem if I wont do my part. The best way to accomplish this is to be honest and straightforward with the patient. There is no need to threaten him with blindness if he doesnt comply, but you need not be apologetic when telling him he has a serious chronic illness.

Along these lines, the third important aspect of communication is empathy. If you show concern for the patient, he is more likely to heed your advice. If you are distant and aloof, he will have less incentive to believe you truly are interested in his care.

I firmly believe that patients must assume a certain amount of responsibility for their own care. But equally important, this responsibility of theirs compels us to give patients the tools they need to take care of themselves, at least those tools that we can give them. One of those is creating the environment that care is a two-way street.

As for the patient in this case, she has returned for subsequent care and currently is complying. Hopefully, this time it will be for life.